Wei Leng Tay’s works may abstract with geometry, colour, and form, but they are full of rich narratives. Just like how photographic and visual documents can influence memory and our perception of history, as her solo exhibition, “Staring into Voids and Blues”, at Gillman Barracks in October showed.

By reworking archival photographs using techniques, such as digital imaging, historical contact printing, and physical manipulation, Tay, a multimedia artist, demonstrated how the past remains present.

She also raised an important question: how do we remember the gaps and voids in history? “The exhibition continued my interest in human movement and migration, and how photography affects how we understand the world around us,” Tay says.

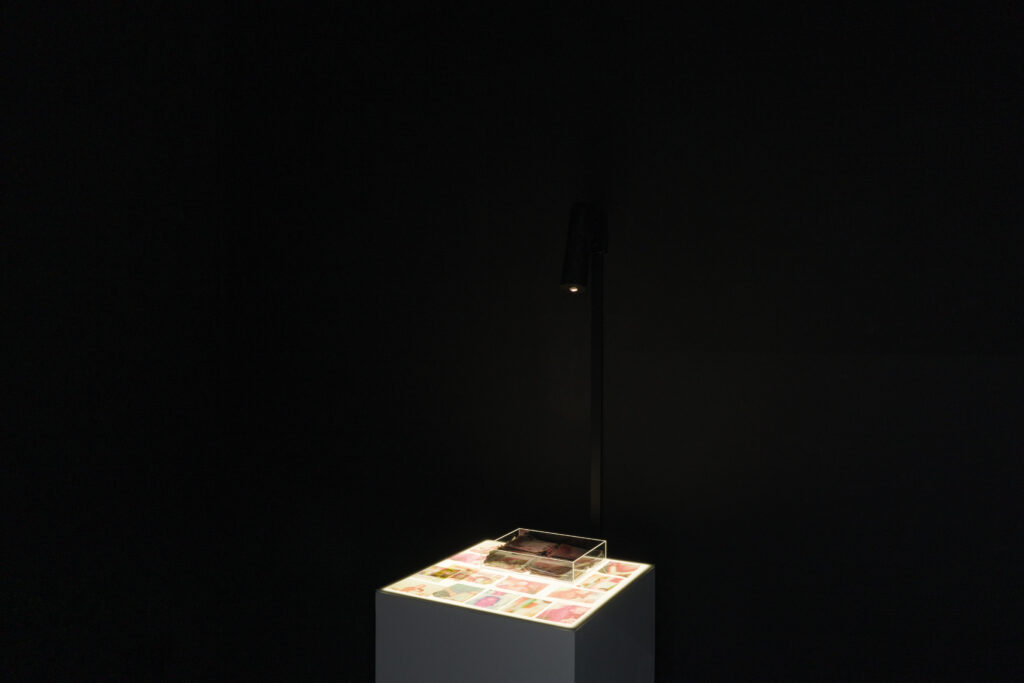

A major part of her storytelling involves the relationship between the form and materiality of the artworks. It changes how one views or touches the work, from tissue prints in ‘You think it over slowly, slowly choose…’ to the sanded-down image of a housing compound in ‘Absence of…’.

“We understand an image not only visually, but also by the way it feels in our hands. All that hand-sanding can affect what you see in the photograph.” Sitting down with us for a one-to-one, Tay talks about her work process, influences, and more.

What was your favourite artwork from the exhibition and why?

The 2024 series ‘3 Nam Lock Street, Singapore’ was my favourite. Using photographs as a starting point, I sanded various parts of a 1962 postcard. Sanding creates voids and absences associated with authority, language or bureaucratic information, allowing viewers to imagine possibilities and realities.

What message did you want visitors to take away from your work?

My intention was to open paths for others to reflect on the topics in the exhibition through their lives and experiences.

How do you select the images to work on?

In most of my work, I use my archive or my family’s photographs and objects. Although the source material comes from a personal place, the photographic depictions, forms, and colours resonate with other families’ experiences and lives. People usually recognise places and things in the photos because they have similar objects.

You were a photojournalist. How did that influence your artistic approach?

Artists often reflect upon conditions in the world and specific issues they see or experience in their work.

My experience in journalism and the instrumentalisation of images in that context informs how I think about visual information and how it is perceived, received, and consumed. It influences what I think about in my practice and what I want to say about images.

My works may produce abstractions and sometimes speculations about the world, but they must be grounded in understanding the context. After all, they begin somewhere. My specific experience in journalism and the people I worked with still contribute to an insistence on rigour in my work.