The temperature can dip to minus 18 deg C in Dawn Ng’s immaculate, light-filled 3,000-sq-ft Singapore studio.

In a flower display freezer, Styrofoam moulds support ice blocks the size of small boulders, each up to 80kg. Pigments sit stacked like geological samples, while wooden panels stand nearby patiently awaiting the end of a long process.

The shelves and worktables are filled with books on geology, poetry, spirituality, and philosophy, along with rocks, crystals, and found objects. She uses these as quiet anchors when contemplating time.

“A lot of the production happens in here,” Ng says, gesturing towards the freezer. Laughing, she shares how her husband, Singaporean entrepreneur and founder of The Lo & Behold Group Wee Teng Wen, insisted she kept a coat in the studio in case the door freezes and jams.

The absurdity of the set-up is not lost on her: “If I get stuck, there’s a bottle of vodka. I’ll just huddle with it and survive Russian-style.” Jokes aside, the freezer is central to a practice that requires waiting, watching, and trusting the process.

Ng has spent the better part of the last decade exploring time: how it stretches, fractures, accelerates, and dissolves. Her latest exhibition, “The Earth Laughs In Flowers”, which opened last month at the Singapore Repertory Theatre, brought that inquiry to its most expansive level. Using frozen colours, controlled melt, and deliberate erosion, she created 12 monumental paintings; one for every month of 2025. She explains, “I’ve always been obsessed with three things: time, memory and temporality; “the things that cannot stay”.

Growing up in Singapore sharpened that preoccupation. In a monoclimatic country with an accelerated pace of progress, time often feels unmarked. Ng says, “When you don’t have seasons, you don’t really have a sense that things are changing and moving forward. Singapore has leapt from Third World to First World in one generation flat. This level of fast-forwarding and speed has real repercussions for how we experience time. Singapore is always embracing the new.”

Her early perspective on impermanence was shaped by the “architectural amnesia” she experienced as a child. “The old HDB flats in Katong I grew up with, the playground, the school—all of that is gone. Identity and memory are continuously erased.”

Photo: Stefan Khoo

Ice’s So Nice

The emotional core of her work is this awareness. The only child of an electrical engineer and a draughtswoman, Ng was born in Singapore in 1982. Her mother, May, quit her job soon after her birth. With time and attention, the two developed a close relationship. Her mother’s influence was actually fundamental. For instance, she would remind Ng very early on that money didn’t grow on trees. It was simply a matter of “let’s make it” if something was desired.

Ng learnt to sketch by copying images from library books into spiral notepads because photocopying was considered extravagant. “There was nothing I enjoyed more than making up stories and cobbling objects to go with them,” she remembers. “I did not know I wanted to be an artist or what it entailed. For me, it was slow and incremental.”

“I did not know that I wanted to be an artist or what it entailed. For me, it was slow and incremental.”

Dawn Ng on finding her way as an artist

Looking back, she mostly absorbed “my mother’s strong sense of self” and “the joy of making things and finding meaning in them”. That belief carried Ng through Georgetown University in Washington DC, where she began in finance and economics before switching to studio art and English without informing her parents. “This canonised view of what being ‘successful’ or ‘worthy’ meant weighed heavily on my generation. There were boxes that needed to be ticked,” she offers, acutely aware of her parents’ sacrifices. “I didn’t want to let them down.”

But by the time she graduated magna cum laude in 2005, the trajectory was clear. Her 20s were spent working in advertising and design at BBH in New York and Paris. “What I took from that world was how to distil and communicate ideas through powerful storytelling and symbolism.”

Even then, she made art in series quietly and persistently. “I knew that if I wanted to do this, I needed to have a good float. Many Singaporean artists struggle to pay for studio rent and materials after graduating from school. Ultimately, the work that leaves the studio is probably five percent of all the paintings and tests done before that won’t see the light of day.”

By 2013, Ng had returned to Singapore for good. Caregiving for her ageing parents played a key role, as did a pivotal conversation with Wee, then a good friend before becoming her husband. He asked her, “Why aren’t you home? You can succeed in a big city, but don’t you see that Singapore is where you can truly shape the narrative? This is your story, isn’t it?”

Her sense of shaping, rather than resisting, intensified around 2017, when ice almost intuitively entered her practice. “I wanted an object that could depict the transition of time,” she notes. “Ice is so child-like, scintillating, magical, and obvious to me. The minute you take it out of its artificial environment; it stands no chance here. It starts to vanish immediately.”

In the following years, there were many trials, failures, and refinements. Today, Ng estimates that nearly 300 ice blocks have passed through her freezer. Each is composed of approximately 33 layers of acrylics, inks, dyes, watercolours, and sand—all new to “The Earth Laughs in Flowers”. “It involves partially freezing things in smaller masses and then assembling them, she explains. “Like Lego or agar-agar.”

When the blocks are ready, they are shattered, sorted like geological samples, and placed on wood. Only then does the melting begin. “It becomes incredibly dynamic and reactionary,” she says. “I need to switch from perfectionist to opportunist.”

Each month of 2025 was assigned its own chromatic vocabulary, drawn from Ng’s lived experience: photographs she took, books she read (especially Samantha Harvey’s Orbital, about six astronauts looking back at Earth), meals she ate, family snapshots, or global news. “Time translates into colour through memory,” she adds. “Time doesn’t exist unless we know what happened in the past, and the past is full of colour, shape, and form. In my work, I strive to give weight and emotionality to time’s presence and passing.”

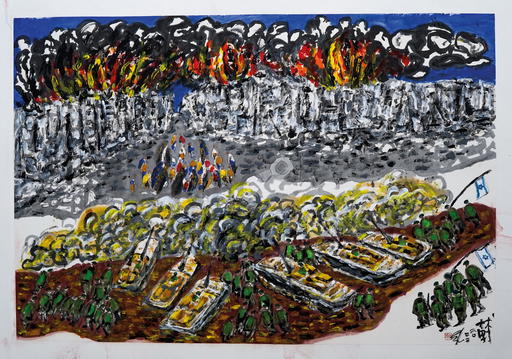

Ng’s ‘January’ painting, for instance, carries the greens and greys of flooding rains in Singapore, fractured by the apocalyptic oranges and pinks of wildfires in Los Angeles. These are interspersed with flashes of Trump, a Francis Bacon artwork, the cracked war-torn landscape of Gaza and a project she curated for New Bahru. The last, masterminded by Wee, has helped shake up Singapore’s hospitality scene.

‘July’ was a sensory overload from a trip to the US—Pride, a fireworks supermarket, rows of Ritz biscuit boxes in Walmart, and her nine-year-old daughter Ava devouring a slice of pizza—but also highly personal. A deep blue emerges in the work, referencing a period of medical fragility following the early birth of her second child.

All In Good Time

Motherhood has recalibrated Ng’s relationship with time more profoundly than any material ever could. She no longer works seven days a week; one day is now kept sacred, away from the studio. “It adds a sense of efficiency and urgency to things for me,” she reflects. “Maybe this is mum-guilt, but any time away from my children is time taken away from them. Hence, my time away has got to count.”

This understanding is embedded structurally in her work. Each painting follows the same rhythm: a month to build the ice block, a single day for the melt, then another month of refinement. By tilting the panels north, south, east, and west, using fans, heat lamps, and ramps, she controls the flow of water. “Billowing occurs when heat lamps are turned on and off. Fan control causes gushing. With this, I carve out a language of islands, volcanoes erupting, and flowers exploding.”

Held in the black-box space of a theatre, “The Earth Laughs in Flowers” was conceived like a time capsule: 12 paintings, one year, frozen mid-flow. The conceptual frame extends beyond human to geological or deep time. Satellite images of Patagonia, Peru, and other locations led Ng to a simple realisation: mountains and valleys everywhere are shaped by the same forces.

“I approach each canvas as a micro planet, and mirror the primary forces that sculpt planetary landforms over millennia: wind, water, time, gravity, and heat. They make art on the Earth.” The exhibition’s title, borrowed from Ralph Waldo Emerson, speaks to this humility before scale: “We think we own land, we think we own time. Ultimately, we return to it.”

While her work has grown more cosmological, Ng herself remains grounded by her family. She and Wee, who met through overlapping school circles when she was 18, are both introverts, deeply committed to their respective fields. “Teng and I are both fiercely independent but strongly intertwined. We are both excited by beauty, ideas, and stories,” she lets on, adding that their conversations range seamlessly from work to the mundane logistics of daily life. She credits his strategic way of thinking for influencing how she structures her studio and long-term projects.

Later this year, Ng will unveil Sunset, a 100-minute cinematic time-lapse film created in collaboration with Welsh composer Alex Mills. It asks, “What would you hear if this was the last sunset you ever saw in your life?”

The film documents the collapse of a hemisphere of frozen pigments, accompanied by an immersive soundscape of breath, strings, voices, lullabies, and even NASA recordings. Ng is also preparing ‘Big Big Small Small’, a sound sculpture performance with vocalist Joanna Dong and musician Chok Kerong, featuring totems of ink-dripped wood.

A continuation of her enduring obsession, these projects suggest that in Ng’s hands, time does not disappear—it accumulates through precious encounters, leaving its mark.

For more inspiring stories in a+ all year round, gift yourself or loved ones a digital subscription.

Photography Stefan Khoo

Styling Chia Wei Choong

Hair Christvian Wu

Makeup Keith Bryant Lee, using Chanel Beauty

Photography assistant Alif

Styling assistant Megan Lim