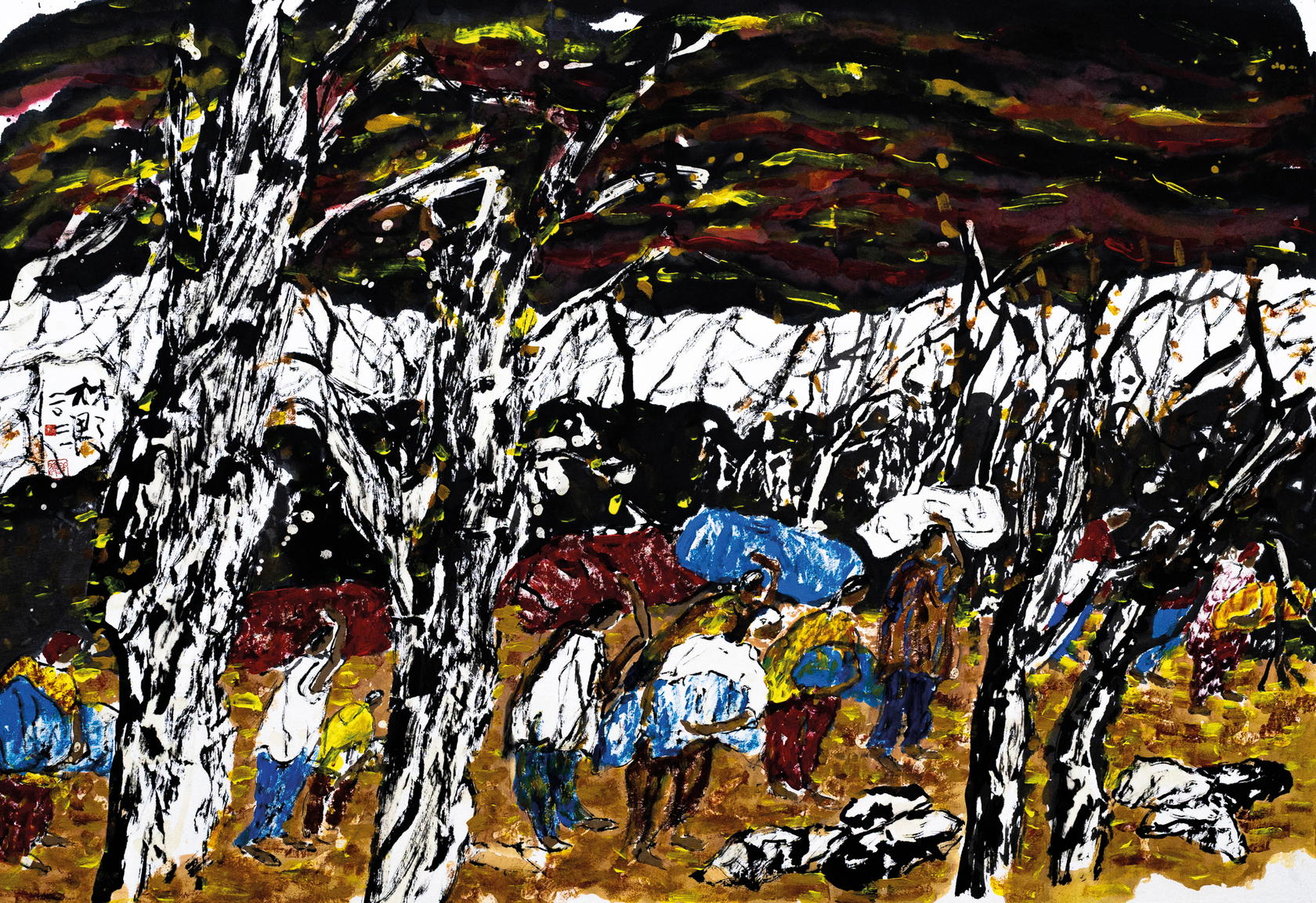

A procession of figures populates Lin’s “Story Of Nanyang”. In this series, dockworkers bend beneath invisible weights, farmers pick durians at dawn, fishermen dry fish on the beach, and workers tap rubber trees.

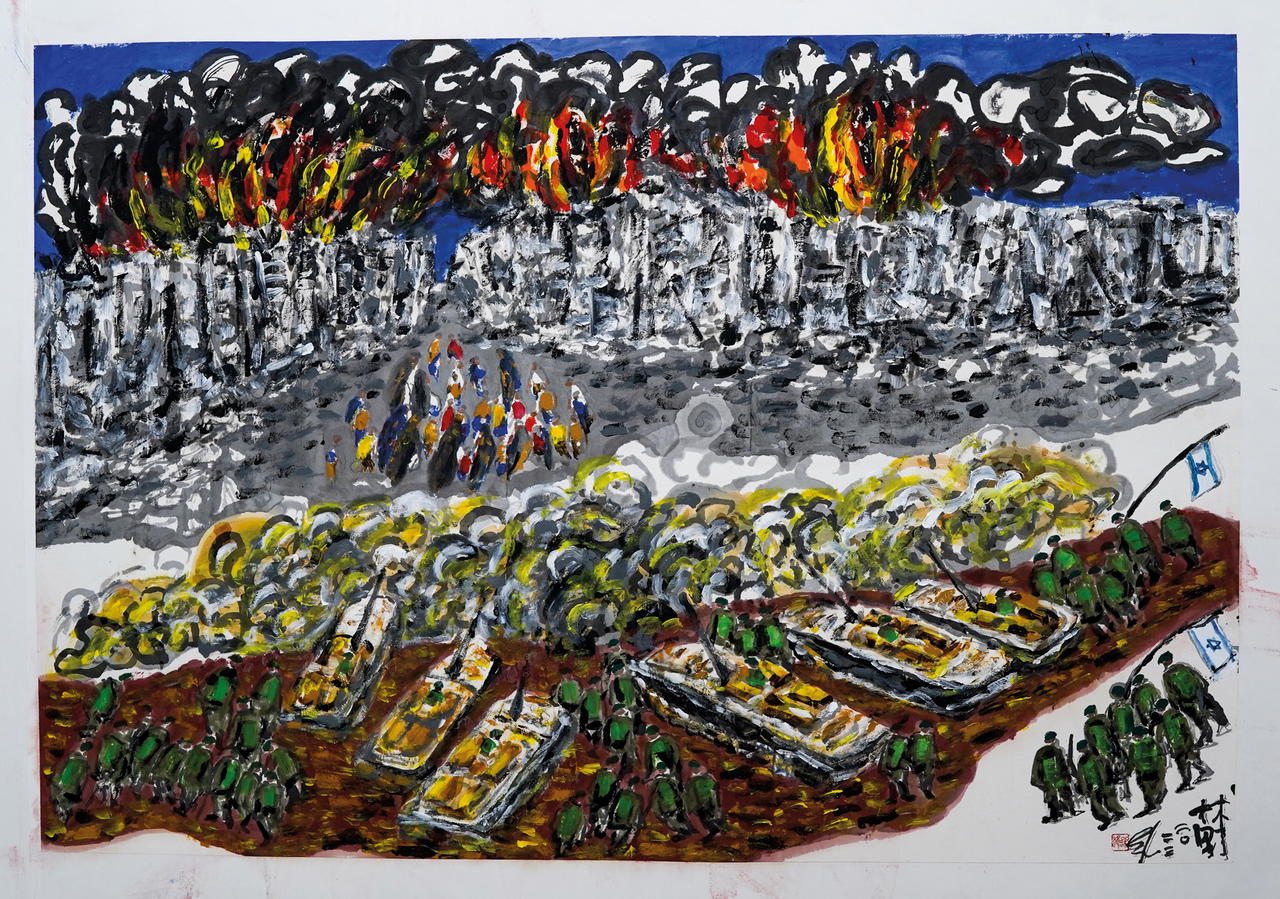

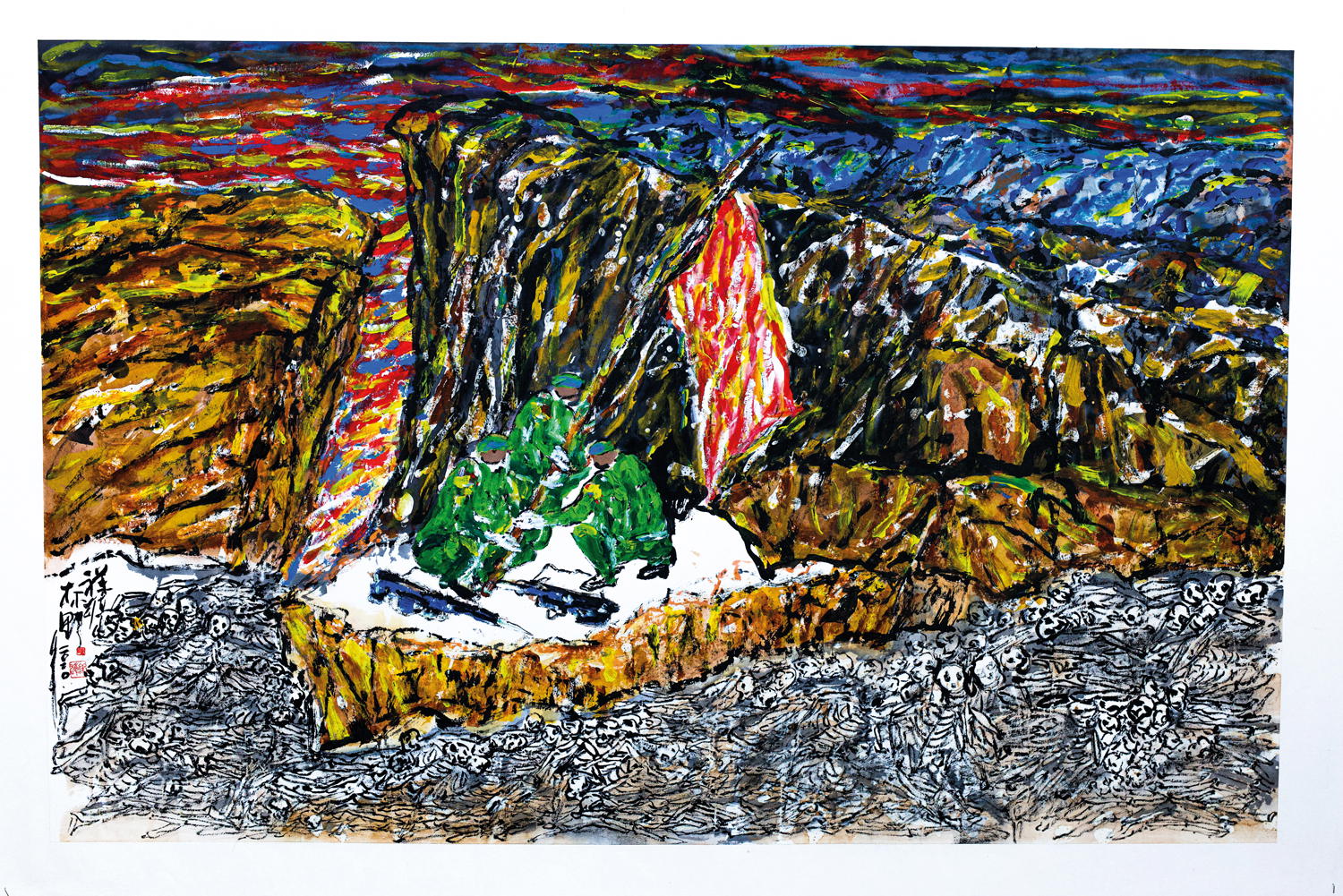

With “The Vicissitudes Of Life”, the mood darkens. Ink, pigment, and wax compress histories rooted in fragmented bodies, scorched landscapes, rivers of blood, refugees escaping war, the impoverished rummaging through rubbish heaps. Rather than soothing, these works compel remembrance in their lasting statements.

In addition, both have found a permanent home at the Lin Xiang Xiong Art Gallery (LXXAG) in Penang, where two galleries also bear the names Story of Nanyang and The Vicissitudes Of Life.

Since opening last December, LXXAG is arguably the artist’s most ambitious project yet. Rather than a museum of contemporary art, it is a declaration of art as a diplomatic and moral force for peace as the Chinese-born Singaporean artist and CNMC Goldmine Holdings Limited CEO believes art is never ornamental but represents survival, observation, and accountability.

His story begins with a rupture. Born in Guangdong in 1945, he lost his mother at 11 during China’s Land Reform Movement. This influenced his early life long before it affected his art.

Following that, he joined his father, a coolie, in Singapore. As a child growing up in poverty, he sold newspapers, polished shoes, and worked on docks. Lin says, “Chinese civilisation teaches that when you are poor, you must take care of yourself; when you are rich, you must take care of others. That idea comes directly from my painful childhood.

My mother visited me in my dreams every night, telling me to work hard and fight for my life because she believed I could make it.”

He studied at the Singapore Academy of Arts before moving to Paris, supporting himself while pursuing his studies. “I did what I could to survive. Perhaps God wanted to train me to be a good person. I used that strength as the foundation for my art,” he says.

It was in Singapore, where Lin came of age artistically, that this foundation was laid. The city was the crucible of the Nanyang style of painting developed by migrant Chinese artists such as Liu Kang, Cheong Soo Pieng, Chen Chong Swee, and Georgette Chen who fused Chinese ink traditions with Western modernism and Southeast Asian subject matter to create a new visual language.

As a result of encountering these artists early in life, Lin absorbed their belief that art must be rooted in lived experiences and local reality. As a matter of fact, Liu Kang became a mentor. Their relationship was built on dialogue, guidance, and shared values. “He told me one simple truth: to be a good artist, you must study culture, philosophy, history, and human nature. Technique alone is not enough.”

This advice anchored Lin’s practice, positioning him as part of a younger generation that extended Nanyang’s legacy rather than replicating it. Currently, he is recognised as part of the New Nanyang School, whose artists carry its spirit forward in a fractured and globalised world.

His visual language is characterised by a distinctive technique that combines ink, rice paper, wax, Western pigments, brushwork, and spatial depth. In his view, beauty alone is insufficient. “The discomfort you feel when looking at my work is intentional. My paintings are historical documents of society.”

War, forced migration, poverty, climate change, and the human condition recur not because they are relevant, but because he understands them well. “Art can make people cry, feel pain, and reflect. It has power because of that. Artists are weak in isolation, but when they connect with leaders, presidents, and policymakers, they become stronger.”

In 2016, Lin presented “Art for Peace” at Unesco House in Paris, making this belief institutional. With the exhibition, his work was explicitly positioned within the realm of cultural diplomacy, demonstrating that art could serve as a bridge between civilisations during geopolitical turmoil.

Last year, Lin, a board member of the Paris-based non-profit Leaders for Peace, launched its “Presenting Peace Through Art” initiative, which provides an avenue for artists to engage with former heads of state, policymakers, and thinkers around the world. His artistic independence comes from his entrepreneurial success at CNMC: “Gold mining gave me freedom to keep my art pure.” As he has never sold a painting, this freedom is absolute.

“If one day a buyer wants to acquire my paintings for peace, education, or a foundation—not for profit—then we can talk,” he says. “Money is a tool, not the goal. It must serve humanity.”

This philosophy culminates in LXXAG. Shaped like a sea turtle—a symbol of longevity, wisdom and resilience in Chinese culture—the RM100 million (S$31.6million) museum occupies 86,111 sq ft in Penang’s Light Waterfront precinct. In addition to showcasing more than 400 of Lin’s works, it will also host international symposiums, artist residencies, and educational programmes.

The Lin Xiang Xiong Art Gallery represents a remarkable shift in Southeast Asia, especially because it is a privately founded contemporary art institution driven by conscience instead of collecting power.

His goal, Lin tells us, is modest and radical. “Art is not a weapon. It is a soft power, a force that slowly alters people’s minds. If minds change, society changes.” Peace, he hopes, will follow.