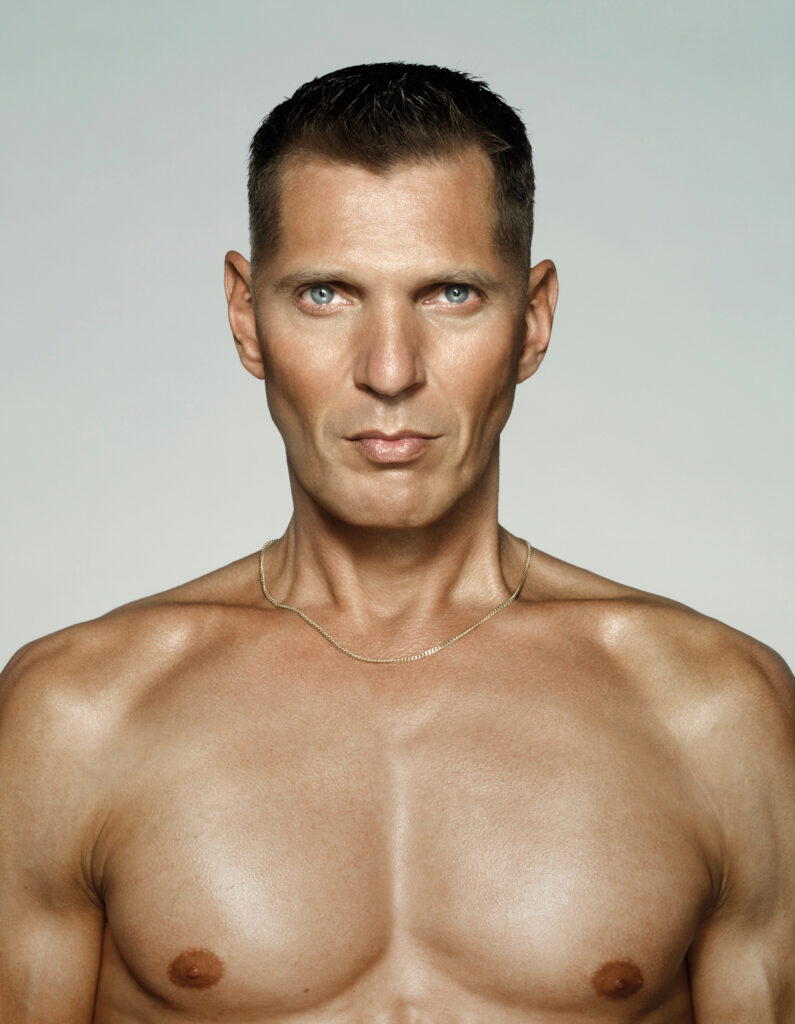

In Erwin Olaf’s art, paradoxes played a major role. It was meticulous yet emotional, seductive yet political, and glistened with glamour even when it spoke of pain. His carefully-lit scenes—women on the verge of tears, men caught in masquerade, the elegant and the excluded—reflected moral questions of our time: Who decides what is beautiful? Who gets to belong? When conformity is easier, how can we remain free?

Two years after his untimely death from emphysema at 64, Olaf has finally arrived at the museum where he always dreamed—and sometimes doubted—he belonged: Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam. “Erwin Olaf – Freedom” (until 1 March 2026) is the first museum retrospective since the artist died and explores how four decades have reshaped photography’s look, feel and fight.

Born in Hilversum, the Netherlands, in 1959, Olaf came of age during the turbulent late 1970s and early 1980s. His camera served as both armour and invitations. “It gave him the freedom to approach people,” recalls Shirley den Hartog, his long-time manager and director of Studio Erwin Olaf, and the founder of Foundation Erwin Olaf. “He wasn’t someone who walked up to strangers, but with a camera, doors opened.”

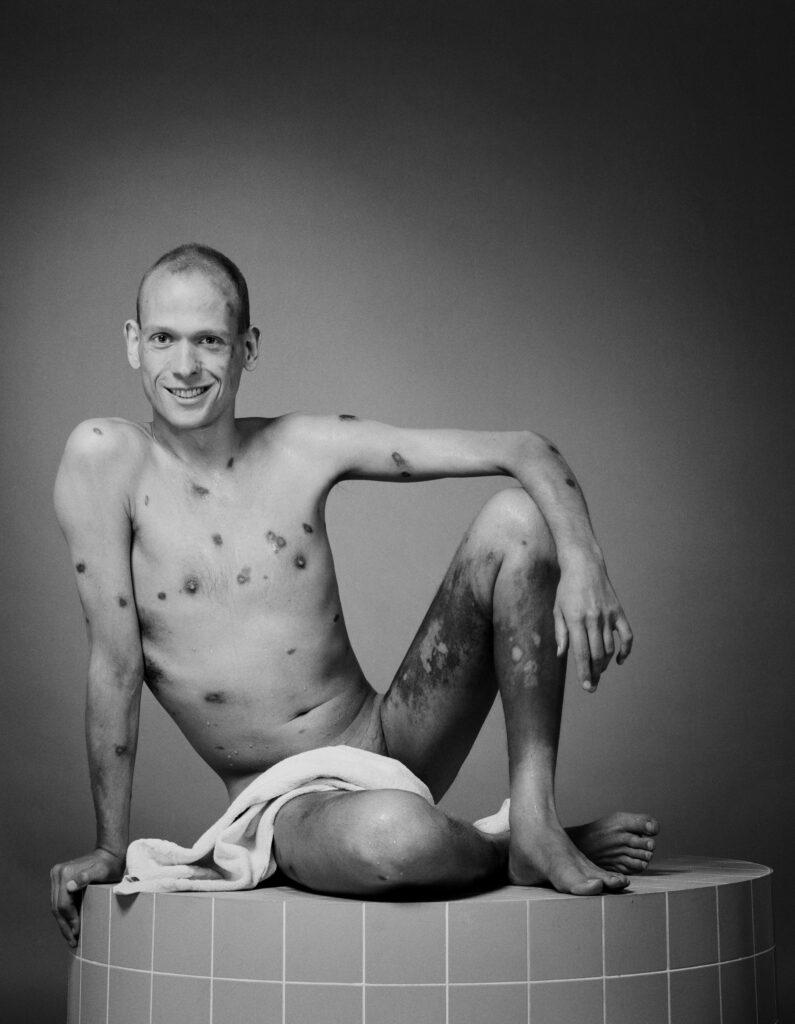

In his early photojournalism assignments for Dutch magazines Vrij Nederland and the LGBTQ+-related Sek, he was thrust into the protests and underground clubs that defined Amsterdam’s queer liberation movement.

Olaf had already turned reportage into theatre by the time he won the Young European Photographer of the Year award in 1988 for his ‘Chessmen’ series, which explored power dynamics and sexual awakening through provocative, stylised images that resembled chess play.

“All the themes that came back later in his work were already there in the first five, six years of his photography,” observes den Hartog. “They contained the DNA of everything that followed: his fascination with the body, democracy, and individuality.

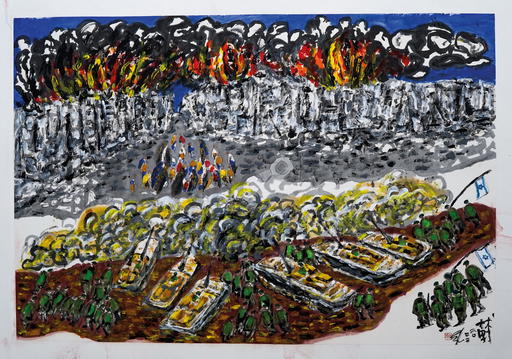

The concerns he had about freedom, populism, and identity were already evident when he was 18. It’s sad because they are all in danger right now, and his concerns remain valid.” In the following three decades, the Erwin Olaf’s series—‘Royal Blood’, ‘Rain’, ‘Hope’, ‘Grief’, ‘Berlin’, and ‘Im Wald’—merged Old Master lighting with cinematic precision.

Under the perfection pulsed a call for action and understanding. “He wanted people to see beyond the surface,” says den Hartog. “He wanted people to be responsible for what is going on around them and to react appropriately.”

ART BEFORE EVERYTHING else

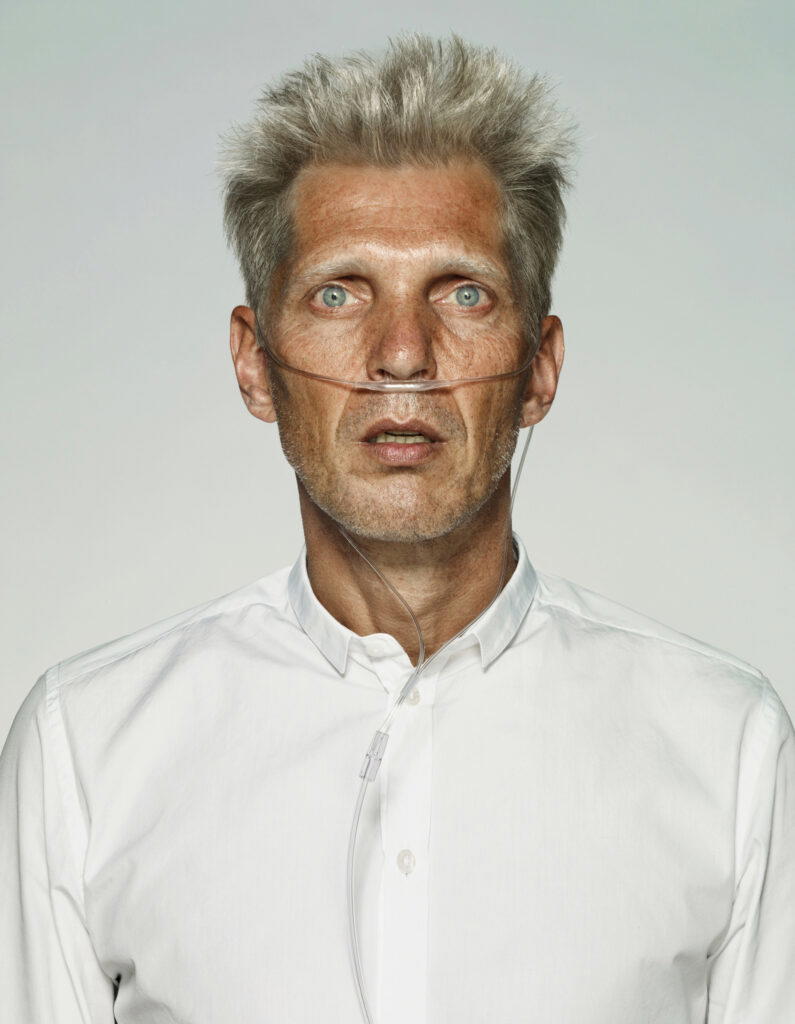

The experience of illness intensified that awareness. Despite his disease, “Erwin felt more than others that his life was ending, but he did not stop,” den Hartog says. Even when ill, he turned mortality into art.

In 2023, after having his two sick lungs transplanted, he created a self-portrait of himself in the hands of his surgeon one hour after the operation. His sudden death weeks later left For Life, an unfinished film about life and death, on his editing table. “That was Erwin. He put his art before everything, even his life,” she adds.

The Stedelijk exhibition, curated by Charl Landvreugd in collaboration with den Hartog, honours Olaf’s final wish. “It was Erwin’s last desire to have an exhibition at the Stedelijk,” den Hartog explains. “He’d had mixed feelings about the museum for years, but before he died, he saw it changing. His opinion softened, and he felt ready.”

“Erwin Olaf – Freedom” occupies the museum’s main galleries, spanning his early black-and-white activism through to luminous colour studies of solitude and grace. The title distils everything Olaf lived for. “Freedom was his motor,” den Hartog shares.

“Freedom to be who you are, freedom to love who you want, freedom to express yourself without fear or judgment. That’s why he fought so hard against injustice or hypocrisy. That was his dream: a world where we stop judging people by how they look or their status and accept that diversity is the essence of life.”

Through images of drag queens, ageing bodies, and poised bourgeois interiors, he chronicled both the cost and beauty of liberation. The questions he asked were moral, not aesthetic: Are we honest? Do we see each other fully?

RADICAL EMPATHY

Erwin Olaf Foundation, established by den Hartog in 2024, follows the same instinct and aims to protect the archive, nurture young talent, and perpetuate his activism. “Half of the foundation is about craftsmanship,” she explains. “We support mid-level students who are talented but often overlooked because they are not in higher education. They are the makers of the future.”

The other half is devoted to advocacy. “Erwin cared deeply about the rights of transsexuals, women, the elderly, and freedom of speech. We want to keep that spirit of engagement alive through projects that inspire people to act, not just complain.” In that sense, “Erwin Olaf – Freedom” is more than an exhibition; it’s an inheritance.

“If you leave the exhibition thinking that even a small gesture can make the world a better place, then you contribute to a better society.”

Shirley den Hartog, Founder, Foundation Erwin Olaf

Across rooms glowing with oscuro portraits and silent film loops, Olaf’s voice resonates—playful, defiant, tender. Den Hartog and Landvreugd eschew chronological rigidity, preferring to trace emotional threads such as desire, discipline, rebellion, and reflection.

Iconic series such as ‘Fashion Victims’ and ‘Paradise’ correspond with later works like ‘Skin Deep’, ‘Shanghai’, ‘Palm Springs’, and ‘April Fool’, shot during the pandemic, in which Olaf appears as a clown wandering through an empty supermarket—absurd yet deeply human. “He always reacted to what was going on in society,” notes den Hartog. “Even his anger or fears became part of his work.”

Visitors will take away the impression that Olaf’s ultimate subject was compassion, not beauty or provocation. His art insists that empathy itself is a radical act: “If you leave the exhibition thinking that even a small gesture can make the world a better place, then you contribute to a better society.”

ACCEPTING LIFE AS IMPERFECT

The exhibition concludes with For Life, an incomplete video Olaf started shortly after his transplant. It depicts peonies in bloom and decay, reflecting life’s transience. Having started the series for his mother, he decided to make one for himself as well. Ultimately, it’s about accepting that everything fades, and life is imperfect, even for someone like him who was a perfectionist.

“For Erwin, every self-portrait was a form of therapy—cheaper than a shrink,” divulges den Hartog. “When he turned 50 and struggled with his appearance, his self-portraits ‘I Wish’, ‘I Am’, and ‘I Will Be’ helped him accept himself. In ‘Im Wald’, he drew strength from watching his husband walk away into the forest, finding solace in death’s inevitability.”

The world Olaf photographed—glossy, staged, saturated—was never pure fantasy. It was his way of confronting reality with dignity and drama. He made vulnerability glamorous, difference heroic, and deficiency sublime. In the city where he once roamed as a shy young man with a camera, his images now stand tall as radiant reminders that freedom, like art, can never be taken for granted.