Heritage is often seen as a mark of pedigree, but it truly embodies the legacy of skilled hands, tools, and the subtle refinements tthat make a brand such as Vacheron Constantin so unique. For 270 years, it has approached time as a continuous journey of research and innovation, building on the trial and error of one generation for the benefit of those to come.

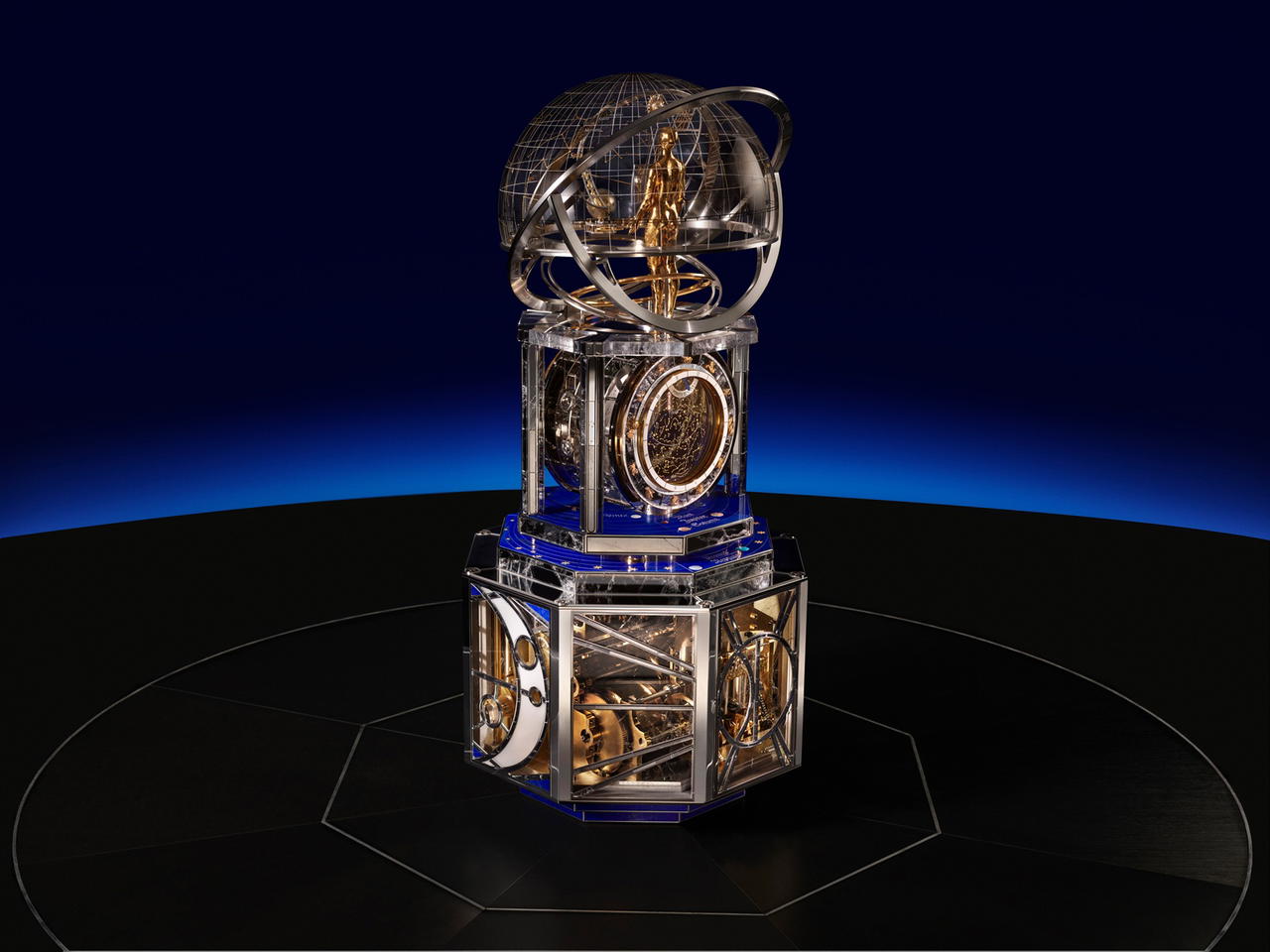

This accumulated knowledge has led to the creation of La Quete du Temps, an impressive astronomical clock that combines high watchmaking, automata, and decorative arts. The masterpiece—over a metre tall—represents a collaborative act of human ingenuity, uniting experts from many disciplines for a single purpose. It now takes centre stage in an eponymous exhibition at the Louvre, on view until 12 November, a result of Vacheron Constantin’s partnership with the museum since 2019.

In this highly historical house, clockmaking is not a detour but a central theme. Vacheron Constantin has consistently turned to clocks for their scale and impact, from court commissions in the 18th and 19th centuries to highly sought after pieces from the 1920s. More recent notable creations include L’Esprit des Cabinotiers (2005), a secret clock developed with automaton François Junod, its Arca clocks (2015), and the Métiers d’Art Copernicus Celestial Spheres (2017). It reunites with Junod and collaborates with master clockmaker L’Épée 1839 this year to create a piece unlike anything it has ever undertaken before.

A work of monumental scale and presence, La Quete du Temps is composed of three interconnected sections: the dome, the astronomical clock, and the base. Beneath a 40-cm glass dome painstakingly hand-painted with a Northern Hemisphere sky, a gilded bronze automaton portraying a humanistic astronomer stands as if at the centre of the universe. In front of him, a 3D precision moon moves along a semicircular retrograde track, and day and night are shown at his feet. Around him, hour and minute scales float in deliberate disorder, serving as a poetic reminder that time can be observed as well as measured.

Behind the scenes: La Quête du Temps

It is fitting that the dome depicts the very sky of the maison’s origin, with the constellations positioned exactly as they appeared over Geneva at 10am on 17 September 1755, marking the exact moment Jean-Marc Vacheron signed on his first apprentice. It is a fact verified by astronomers from the Geneva Observatory. They also confirmed a rare Sun–Jupiter conjunction and the visibility of Venus, Mars, Jupiter, and Saturn.

An astronomical clock with two dials sits in the centre. Four layers of mirror rock crystal make up the front, which reads the time via nested circles and arcs for intuitive legibility. An oversize tourbillon sits at 12 o’clock and a 15-day power reserve appears as twin retrograde brackets at the dial’s sides, their tracks set with lapis lazuli and moonstones shaded from blue to white. The leap-year cycle is displayed in a window beside the tourbillon, and days and months are shown in apertures at 10 and 2 o’clock.

An anchoring circular 24-hour display carries a hand-engraved sun and moon gliding over a guilloche field of radiant rays, while a lacquered ring fades from blue to white to chart day into night. To the left and right, bevelled crystal scales plot sunrise and sunset with retrograde hands, and a semicircular retrograde date right below boasts a rock-crystal inlay with gold numerals. On the reverse dial, a rotating Northern Hemisphere celestial vault displays the stars in sidereal time. A second retrograde power reserve sits above, and three concentric rings record months by number, seasons, equinoxes, and zodiac signs.

All this rests on a two-tier plinth inlaid with plaques of old-mine lapis lazuli that map the solar system. Each planet is rendered in a hard-stone cabochon with its name in mother-of-pearl inlay. Featuring rock crystal, lapis and quartzite, the base bears a geometric frieze depicting the sun and moon.

Throughout the astronomy and calendar work, the eye is drawn to the automaton in the dome the moment it moves. Featuring an intrepid astronomer who performs a three-part, 90-second sequence on demand or scheduled up to 24 hours in advance, Junod’s work of art evokes wonder and surprise.

In addition, an integrated mechanical “music machine” based on a metallophone with Wah-Wah tubes plays original melodies by French singer-songwriter Woodkid. First, a melodic alert awakens the figure, which surveys the scene, points to the day-night markers, and then traces the moon’s retrograde path. Next, it gestures to the constellations while the music plays, then returns to rest.

The finale is a time-telling display: the figure indicates the current hour and minutes on the suspended scales inside the dome. Because the numerals are deliberately scrambled and not sequential, the gestures vary with every activation, even minutes apart. Making that variability legible demanded a mechanical memory. To achieve 144 unique gestures (12 hours × 12 five-minute steps), the team built a cam-driven “brain” of 158 cams connected to the clock via a mechanical time-memory, with a separate mechanism driving the melodies.

This anniversary clearly delivers a powerful message: tradition is both rigorous and ravishing. La Quete du Temps stands as both a testament to this legacy and a captivating performance in its own right.