Joel Meyerowitz credits Leica with shaping not just his photography, but his way of seeing. “It’s a harmony between the living moment and the sensual, emotional, and visual moment. Imagine Leica as an observer who records your responses to the world around you. Faithfully records them as its cameras will not fail you.”

Long associated with Leica’s rangefinder models, including the M2 and M6, the American photographer is both a loyalist and a purist. Though he describes himself as an “attentive flâneur,” Meyerowitz was the only photographer granted unrestricted access to Ground Zero in 2001—a quiet witness with a Leica in hand.

His desire to bear witness to history echoes Leica’s centennial celebration this year at its headquarters in Wetzlar, Germany—where it all began with the launch of the Leica I in March 1925. In honour of the milestone, the Ernst Leitz Museum presents “Joel Meyerowitz: The Pleasure of Seeing”, an exhibition of 100 photographs that reflect both a personal and collective visual history. The show is part of 100 Years of Leica: Witness to a Century and runs until 21 September.

To understand the importance of this milestone, it’s worth tracing Leica’s origins. The company was founded in 1869 as Ernst Leitz GmbH, which produced microscopes. The Leica name—derived from “Leitz” and “camera”—only came into official use in 1986, long after the brand had become synonymous with compact, high-quality cameras.

The Leica I traces its origins to the Ur-Leica, a prototype built in 1913–14 by Oskar Barnack, a Leitz mechanic and amateur photographer. Struggling with heavy cameras due to asthma, Barnack created the compact “Liliput” using 35mm cinema film—marking the first use of film in landscape format and a breakthrough in photographic technology.

“I hereby decide to take a risk!” declared Ernst Leitz II as he committed to mass-produce Barnack’s invention. The result was the Leica I, introduced at the 1925 Leipzig Spring Fair in Germany.

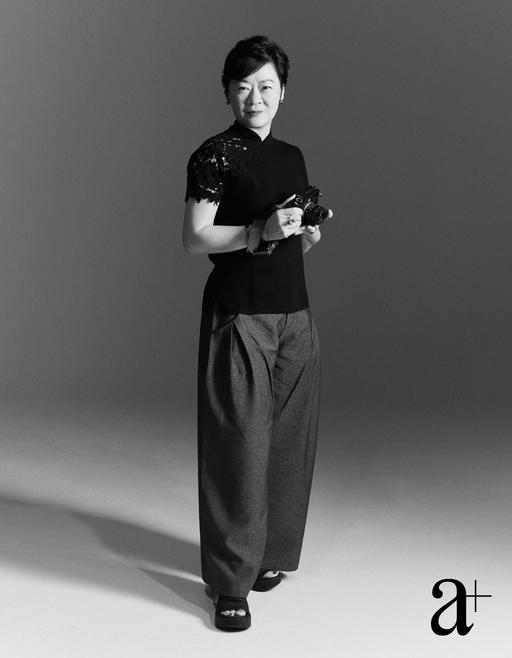

“The Leica I revolutionised photography,” says Karin Rehn-Kaufmann, Art Director and Chief Representative of Leica Galleries International. “It was compact enough for street photography and reportage, something entirely new at the time.”

Equipped with an Anastigmat 50 f/3.5 lens, the Leica I quickly became a hit, establishing the 24×36mm format as the global standard. Early adopters included visionaries like Alexander Rodchenko, Gisèle Freund, and André Kertész. Around 1,000 units were sold in its first year—laying the groundwork for Leica’s legacy.

Rehn-Kaufmann credits the brand’s enduring appeal to its philosophy. “We never stopped making film cameras,” she notes. “Other companies stopped and now they’re restarting because it’s trendy.”

Past inspires present

Over the following decades, Leica continued to refine the rangefinder system first introduced with the Leica I. As photography evolved, so did the company’s engineering—more advanced optics, sturdier builds, and improved viewfinder technology.

This ongoing innovation led to the launch of the Leica M3 in 1954, a landmark model that redefined 35mm photography and laid the foundation for the M series. It embodied everything Leica stood for: intuitive handling, mechanical precision, and timeless design—a legacy that still defines the brand today.

The current Leica M lineup reflects this ethos, offering both analogue (M6, MP, and M-A) digital models (M10 and M11), all designed with a minimalist approach that prioritises essential controls.

The rangefinder system delivers a bright, high-contrast view that extends beyond the frame, with bright-line frames that auto-adjust to the mounted lens (28/90mm, 35/135mm, 50/75mm), enabling fast, accurate focusing—even in low light.

An excellent example of Leica’s design-first philosophy is the M Monochrom, a digital rangefinder with a black-and-white sensor and no display. “Why go back? Everyone asked. Why make a camera that shoots only in black and white?” Rehn-Kaufmann recalls. “But that’s what Leica is about, staying different, not because it’s fashionable, but because it’s meaningful.”

Leica is also celebrating the centennial with a series of limited-edition cameras under the 100 Years of Leica banner. The D-Lux 8, the Sofort 2, Trinovid 10 x 40 binoculars, and the flagship Leica M11-D 100 Years of Leica set with two lenses are among them.

With its minimalist design, the M11-D 100 anniversary set pays homage to the original 1925 Leica I. A high-gloss black finish covers the top and solid brass base plates. As on the Leica I, the red logo is removed and the strap eyelets are omitted. Controls—nickel-coloured and aluminium—mirror the original’s distinctive cross knurling.

It features a leather wrap, a semicircular shutter button, and an engraved accessory shoe serialised from 001 to 100 to distinguish it from other cameras. The set also includes the Leica Summilux-M 50 f/1.4 ASPH and the Leitz Anastigmat-M 50 f/3.5, the latter being a modern take on Leica’s first-ever lens.

design drives emotion

Beyond precision and aesthetics, Leica cameras offer a deeply sensory experience. “Whether it is the click of the shutter or the weight in your hand, everything is designed to connect you to the moment and help you see differently and feel more deeply,” says Rehn-Kaufmann.

She also highlights the Leica community, a global network of both professionals and enthusiasts. It has 29 galleries worldwide, hosting around 150 exhibitions a year. The Leica Oskar Barnack Award, established in 1979 on Barnack’s 100th birthday, honours images that capture the relationship between humans and their environment, echoing the spirit of Barnack’s images.

A centennial highlight for Rehn-Kaufmann is “In Conversation: A Photographic Dialogue Between Yesterday and Today”, which pairs 12 Leica Hall of Fame photographers with emerging talents from their home countries. Each month, a Leica Gallery hosts an exhibition exploring this generational dialogue. This month in Melbourne, Steve McCurry is shown alongside rising photographer Jessie Brinkmann Evans.

“In terms of strategy, I think we’ve done more right than wrong,” reflects Leica CEO Matthias Harsch. He attributes its technological advancements to successful partnerships with brands like Huawei and Xiaomi. He also singles out the Leica Q series of fixed-lens, full-frame cameras with both manual and automatic controls as one of Leica’s hero products.

Looking ahead, Harsch is excited by the challenge of preserving Leica’s soul while innovating in a rapidly changing digital world. The Leica Lux app lets iPhone users emulate the signature look of Leica lenses, such as the Noctilux-M 50 f/1.2 and Summilux-M 35 f/1.4. Developed in-house, it adapts Leica’s legendary lenses for the digital age.

What lies at the heart of Leica’s century-long success? The company’s dedication to design. “We’re very Bauhaus,” says Harsch. “Everything reduced to the essentials.” Leica’s Munich team ensures that even a hypothetical Leica ashtray is pared back, functional, and beautiful. “We could make even that a great product,” he chuckles.