Ennui shaped Ho Tzu Nyen’s childhood. It was a time before social media and constant entertainment, and in this aching yawn of a crucible, Ho’s imagination flourished. “Boredom is an egg from which future plans are hatched,” he says, smiling.

The heat of afternoons, when the sun makes its final humid hurrah for the day, was one of his fondest memories. At that moment, flitting between consciousness and drowsiness, Ho would have intense, lucid dreams. He doesn’t remember the contents, but the sensations have stayed with him ever since.

He dabbled in art, too. But he wasn’t a prodigy by any stretch of the imagination. His parents sent him to art class to learn calligraphy and Chinese ink landscapes, and he gained knowledge in crayons and watercolours as well. “But I was terrible in all of them, without fail,” Ho says, smiling. “I always get curious when two different paint colours are mixed, so I would blend them on paper. Eventually, all my paintings became grey because all the colours were smudged together.”

Then, there was the VHS player, or video home system. Before DVDs and streaming, this device created new, fantastical worlds for viewers. Ho would always remember the first time he encountered a VHS player. According to him, it opened a portal to a different dimension. A huge film buff, his father regularly rented tapes for the family to watch. Ho was unaware of the plot or the characters in the film, only the pictures pasted on the sleeves. “I saw many strange, wonderful, and terrible films. However, one thing remained constant though. All of them opened my mind,” he says.

Ho recalls one incident vividly. It was late at night and the house was unstirred. Everyone had fallen asleep, except for Ho. Tired of tossing and turning, he snuck out into the living room to watch television. As a film played, Ho saw “the strangest thing”. One scene showed a character’s torso opening and a VHS tape being inserted into the gap. That movie was Videodrome, a cult hit written and directed by David Cronenberg. It won several awards and has been heavily referenced by many auteurs even today.

The scene intrigued Ho. “It did something to me,” he says. “In a sense, VHS tapes and other storage devices are an externalisation of the human brain. Ingesting that cassette made perfect sense.”

The VHS player is a recurring motif in Ho’s life. In junior college, he stumbled upon D & O Film & Videos, a shop hawking VHS tapes in Tanglin Shopping Centre. But the wares weren’t as important as the late shopkeeper, a cantankerous heft of a man named Albert Odell who cared little about profits and more about whether the tapes were rented to the right people. He berated his customers for returning tapes late or God forbid, not rewinding them.

“Every art film lover of my generation must have been subjected to his tyranny,” Ho says, smiling at the thought. Fortunately, Odell gave Ho his stamp of approval, allowing him to borrow whatever his heart desired. Ho’s life and his trajectory as an artist today were shaped by many of these films.

The reason there are five paragraphs dedicated to the VHS player is because Ho is unlike anyone else I’ve ever interviewed. His mind zigs and zags in uncharted directions, but the journey offers interesting sights. It’s not surprising that he also enjoyed science fiction novels, especially Jules Verne’s works, and disliked the tedium of formal education.

His first stab at a university degree, majoring in communication studies, ended with him dropping out. He found the programme boring and only enjoyed a few lectures. Instead of attending classes, Ho spent all his time in libraries, devouring books on art, philosophy, and anything else that intrigued him. One, in particular, grabbed his attention. It was a German Marxist philosopher’s book about modern art, specifically the great French painter and sculptor Marcel Duchamp. “That was the first time I entertained the idea of becoming an artist one day,” Ho says.

‘Fountain’, Duchamp’s readymade sculpture the artist submitted for an exhibition in 1917, appealed to Ho. This upside down urinal convinced him that the purpose of art was to subvert societal norms. “Marcel Duchamp gave me the wrong impression what being an artist was about,” Ho says, laughing. “The only art I was interested in at that time was subversion.”

He dropped out of his then-university to enrol at the University of Melbourne, where he studied art. He was ready to unleash his subversive, creative mind on the faculty and team up with his peers to “bring down the institution of art”. As Ho puts it, “I thought art could be a simple life where I don’t have to do much and coud select ready-made objects like the urinal and call them art.”

Of course, he was completely wrong. His university mates didn’t want to subvert art. They still wanted to create beautiful objects. Ho was shocked. But since he was already there, he remained open and learned as much as he could, while still hewing close to his vision of art. True to form, Ho skipped classes he wasn’t interested in and only attended those helmed by lecturers he got along well with. They became powerful defenders of his work. “I guess they enjoyed having someone with my kind of energy around them,” says Ho, who is still in contact with one of them.

Once again, he used the library intensely and borrowed the maximum number of books. It also had an incredible VHS tape collection, which Ho devoured voraciously, watching up to three films a day. He was learning, absorbing and asking questions. It was a different kind of education, but one that Ho is eternally grateful for. Ironically, he graduated on the Dean’s List.

“Even though I didn’t attend classes, I would dive into the syllabus and check out the readings. I would also surreptitiously include arguments in my assignments about the construction of the course. I took everything seriously and threw myself into the projects because I didn’t want to fail. Failure is a waste of time and money, and I had limited resources,” he says.

An older, more experienced Ho understood that rejection didn’t have to mean suffering. There are many issues in life one might consider less than ideal, but dismissing them outright would be detrimental to your progress. Fortunately, Ho not only learned this important lesson in “strategic living” at the beginning of his budding life, but he also applied it immediately to his subsequent academic pursuits.

And there are many ideas he finds to be conformist and repetitive. Although some might label Ho a troublemaker, he stresses that the act of questioning doesn’t mean criticism. He views it as a vital part of the creative process. Rejected ideas, however, aren’t immediately discarded and forgotten. Rather, he files them away in his mental repository, letting them ferment while waiting for the right moment to let them bubble up again.

“Sometimes, I subvert myself and open up to an idea I’ve been holding back for many years by having prolonged conversations with it. In these moments, I also learn a great deal about myself.”

“Boredom is an egg from which future plans are hatched.”

Ho Tzu Nyen on the importance of being bored in creativity.

In many ways, Ho’s debut exhibition was a subversion of his thoughts. After graduating from the University of Melbourne, he toiled away for two years as an art critic. Although it wasn’t romantic, it paid the bills. But his dreams of being an artist continued flickering valiantly.

Out of the blue, Lee Weng Choy, then-artistic director of The Substation, emailed Ho, expressing a desire to meet him after reading something he wrote. They met, and within an hour of their conversation, Lee offered Ho a chance to create his first solo exhibition.

It was a massive opportunity. By his own admission, he was a nobody back then, and this gamble could have backfired spectacularly. Lee gave Ho a year to prepare before leaving him to his own devices.

Initially, Ho created abstract paintings, but it was a struggle. There wasn’t much flow from the creative faucet. Then Lee visited him to check on his progress and casually asked, “Have you ever thought of making works that are more narrative?”

That question stayed with Ho for days on end. He wrestled with it, unpacking, disassembling and putting it back together again. He knew Lee had a point.

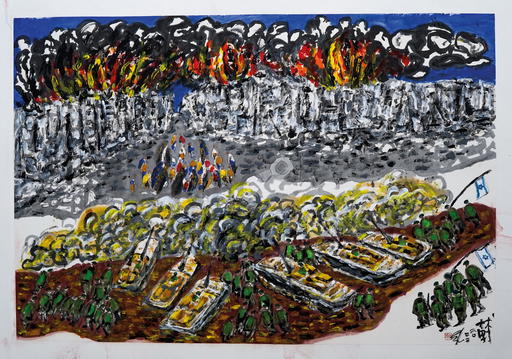

The result was Utama – Every Name In History Is I, an installation comprising a 36-minute film and 20 oil paintings. In true Ho fashion, the artist pushed back against Singapore’s founding narratives by emphasising 14th-century explorer Sang Nila Utama, who gave the city-state its name.

In contrast to my perception of his nonchalant artist persona, Ho was concerned about the reception his first exhibition would receive. He was an unknown quantity creating a video riffing on history and academic research, while weaving in myths and fairy tales. It was a tremendous risk, a subversion.

Utama made waves when it debuted, and Ho felt vindicated. However, he felt it needed to reach more eyes and ears. If your work isn’t seen, are you an artist? He had thrown 18 months of his life into Utama, after all. “Every work I make, I have the delusion that it will change the world, even though history has shown my limits. But I always persist,” he says.

To reach more people, he circulated the film at different festivals, packaged it as part of a theatrical academic performance that he disseminated as lectures in schools, and experimented with different mediums.

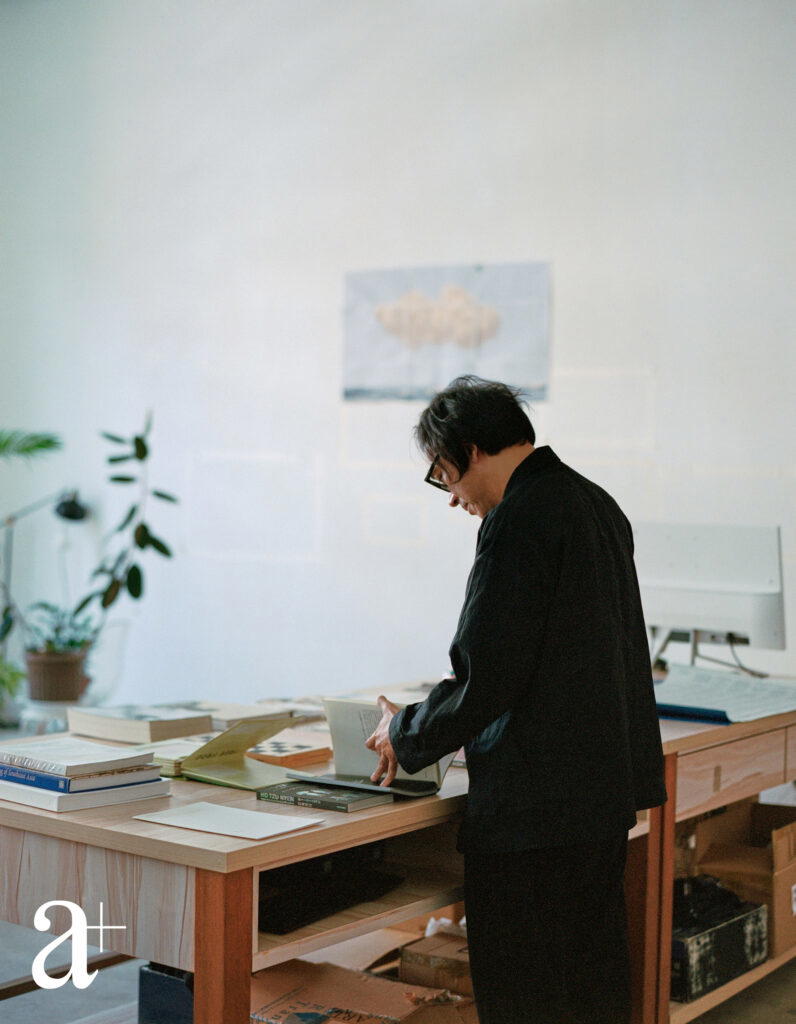

Two decades after Utama’s debut, Ho no longer needs to market himself. His works are sought after by major museums and his exhibitions draw crowds eager to delve into his mental crucible. He’s represented Singapore at several global events, including the Venice Biennale and Cannes Film Festival.

Some have criticised him for creating pieces that are inscrutable and overly intellectual. He disagrees. “My logic is simple. If one person can understand the work, then by extension, everyone can understand it. I am inspired when I encounter great works of art that I cannot comprehend at first glance. However, I feel a deep intuition that there is some logic to this. And it broadens my worldview.”

It won’t be long before Ho’s mystique reaches even more people. He was one of 10 winners of the second edition of the Chanel Next Prize, which awards 100,000 euros (S$144,965) in funding and a two-year mentorship and networking programme. Founded in 2021 as part of the Chanel Culture Fund, the biennial Next Prize aims to “amplify the work of artists… making a difference and redefining their disciplines”.

Ho plans to use the money to improve his artistic infrastructure and his team’s productivity. The seeds of his next project have already been sown. “It will be about power. Unfortunately, our world is now dominated by a negative form of power and problematic political systems. Our democracy is being used to curb someone’s power. I want to rethink it.” The form of this project is still unknown to him. But he imagines it will come to him in the heat of the afternoon, in the limbo between consciousness and drowsiness, when the aching yawn of boredom comes to claim him.

Photography Stefan Khoo

Styling and Art Direction Chia Wei Choong

Hair and Makeup Wee Ming, using Schwarzkopf Professional and Chanel Beauty

Photography Assistant Chong Ng

Styling Assistant Julia Mae Wong