“Grateful” is probably Jackson Teo’s catchphrase. You’ve likely heard or read of what his company — 33-year-old karaoke chain Teo Heng — has been through the last two years. Otherwise, it wouldn’t be too hard to imagine. Yet Teo’s casually amiable demeanour shows no sign of the fact that he’s still recovering from millions of dollars worth of pandemic-inflicted debt.

“We can only accept it,” the 64-year-old founder shares candidly. “Some things are beyond your control. Acceptance is the only way to confront it. Only when you truly do can you solve it, then let it go. So that’s what we did.” Teo tells of the unexpected costs and complicated procedures reinstating the first outlet involved, which alone amounted to $50,000.

That’s also an average monthly loss prior to the reopening; a possibility he didn’t dare entertain after three consecutive shutdowns. “Jin jialat (‘extremely terrible’ in Hokkien). I actually wanted to close down much earlier but I had so many people telling me not to.”

“It was because I was struggling. He saw me break down,” his sister and fellow business director Jean Teo admits. “The worst-case scenario was to hold out until the end of this year.” Like her brother, nothing about her affable nature gives away the emotional turmoil she underwent since the first nightlife reopening pilot programme.

Despite all efforts to abide by regulations and implement measures accordingly, everything came to a halt when cases surged. The same nightmare then repeated twice more with the Delta and Omicron variants. “That’s when I couldn’t take it anymore, because you never expect things to get to that stage,” she recalls, shy of a shudder.

“We were constantly trying to explain it wasn’t that we weren’t willing to operate — we were not allowed to. There was no direction back then… you don’t know when things would take a turn for the better. And it’s not like we didn’t fulfil what was required of us to our best abilities; everything was approved, but still.”

Once again faced with lease re-negotiations, forced penalties and repossession, they culminated in a full-blown panic attack. Jean had to be wheeled into the psychiatric clinic by Jackson because she couldn’t walk, and could barely breathe. When oral medication didn’t work, she received an injection. Eventually, it was Jackson’s encouragement that pulled her through the episode.

“You may find it painful initially, but it gets easier the more you do it. In Mandarin, ‘willing to’ is interesting. It’s made up of the words ‘give’ and ‘receive’. It’s telling you that you have to give to receive.

Jackson Teo

“You will definitely feel a little grief at the circumstances but it’s all about perspective. I told my sister that affairs of the state affect millions of lives. [Teo Heng’s problems] are minute compared to the scale of what the country faces,” Teo says. “You don’t know how much the government is doing. Are they not troubled and dismayed? Of course! They too want to [alleviate the situation]. They are handling major issues and you want to complain about them not [meeting your needs]?”

What moved the siblings most was the help they received from their landlords, especially the private equities, which they list by name. Many empathised during their pivoting period and offered contractual adjustments in their favour. Social media also lent its strength in dark times. Now privy to the impact their closing would have on customers, they were motivated by the acknowledgement and desire not to disappoint them.

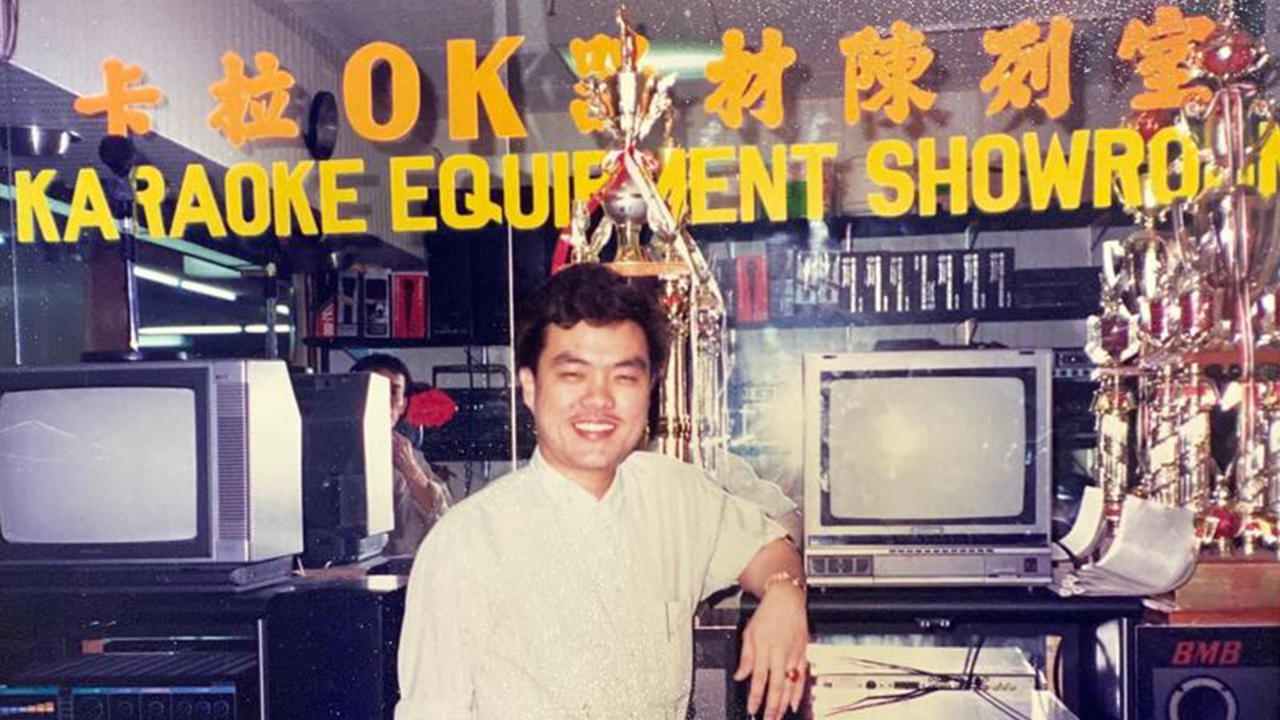

The support garnered shouldn’t really come as a surprise when you see how people-oriented the entity is. They weren’t joking when they said they aspire in the direction of a social enterprise. For the uninitiated, the origin story has Teo as a karaoke systems seller simply wanting to provide a safe space for kids to bide their time; hence the student-friendly prices and family-friendly concept.

In a hypothetical parallel universe where Teo Heng existed for profit and sold alcohol and cigarettes, Teo estimates easily making a comeback or getting out of debt within a year. It’s the most lucrative part of the gig, but one he will never compromise on. “It’s not that we don’t earn anything, but we liken our profit margin to coffee shops and hawker centres, where they work half to death but earn enough to sustain a living,” Teo elaborates.

He had famously refused to cut staff salaries in the first six months of the pandemic, only relenting when straits were dire and letting them work elsewhere in the meantime — only because he really wanted to retain them. Thankfully, he’s had many wanting to return since the reopening. But those are just the fees we’re aware of.

On top of income tax, there are multiple licences mandatory to operate per outlet. And because KTVs currently remain under the umbrella of nightlife, they are charged at rates identical to nightclubs. It’s unfairly difficult to match considering the difference in pax per square foot. Their appeal to demarcate family-friendly karaokes from adult KTVs has yet to see progress, but they understand how it’s a tricky position for legislation if loopholes were to be exploited.

Teo is undoubtedly an advocate of karaoke. There’s a system in every floor of his house, and he books a band for a three-hour jam session every Saturday. It’s a form of release, it takes his mind off matters, and it’s even recommended by doctors. Teo affirms that equipment quality is crucial to him as a veteran vendor himself.

Photo: Teo Heng.

His brand Wasuka (‘I like’ in Hokkien) is testament to the mutual respect he shares with Japanese industry partners and manufacturers. He goes into a fascinating technical spiel about the audio distinction between singers and even languages which have to be accounted for. It’s unfortunately too long for wordcount so should you be curious, you may head down to Katong and find him manning the sales floor (something he still does to this day) to try your luck.

“It’s important to maintain the same attitude from thirty years ago, till thirty years later,” Teo relates, citing the act of donating as what fundamentally enlarged his spirit of generosity. “You may find it painful initially, but it gets easier the more you do it. In Mandarin, ‘willing to’ is interesting. It’s made up of the words ‘give’ and ‘receive’. It’s telling you that you have to give to receive. Your character changes and you start to prosper. Everything will be different because you’ve broadened your approach to life.”

There’s a strong sense of the personal and professional ethic codes this man lives by that inevitably pervades each aspect of his life. Making complex executive decisions, devoting resources to charitable causes, genuinely lighting up when talking about putting customers first; it’s like seeing a living example of what an upstanding citizen should be.

The life advice he spills hardly sounds cliche, because he recognises that it’s often easier said than done. “Whatever we do, we hope to benefit society,” he expresses. “Ultimately, we do it all for the next generation, and the generations after.”

This interview was conducted in Mandarin and translated with reasonable efforts made to ensure accuracy.