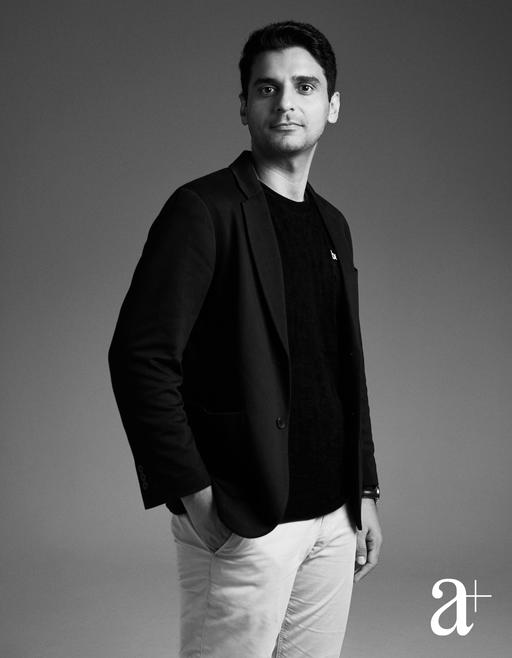

When I first met Ivan Yeo barely two years ago, he’d floated the idea of cultivating an amateur esports community locally, with members mashing and grinding from Yishun to Punggol. Back then, I’d noted a folksy earnestness uncharacteristic of someone leading a rapidly growing VC-funded company with the region in its grasp.

Today, the 32-year-old has abandoned the relentlessly amped, energy drink-fuelled arena of competitive gaming to chart a nebulous new realm: Web3, a decentralised online system based on blockchain technology. His new preoccupation is playing out in Avium, his soon-to-be launched Web3-enabled platform connecting creative industry players from film and animation studios to voice actors.

Yeo, who suffers from motor neuron disorder Kennedy’s Disease, says health issues prompted him to step down as CEO of EVOS Esports. But he’s by no means lost sight of his original lodestar.

“I looked at gaming and the creator economy as a way for me to build the infrastructure enabling gamers’ and content creators’ careers to flourish,” shares the visibly sparer entrepreneur.

In that respect, EVOS’ perky branded videos on steroids have allowed a menagerie of unlikely influencers — among them gauche and gangly adolescents — to shine. But how exactly can that success be replicated through a hypothetical iteration of the internet that’s amorphous at best, and for the unbelievers, thinly disguised marketing spiel bandied about by crypto players?

I dream of a world where people can finally pursue what they want instead of following what society expects of them.

Ivan Yeo

“The creative industry in South-East Asia is talented but highly fragmented, so they have only outsourced (work to) Western studios. What we’re doing here is bringing together animation, film and game studios to build an ecosystem together and that’s only possible in Web3 because with NFTs and tokens, you can enable ownership for everyone,” he pronounces, drawing parallels with Hollywood’s early days of set, studio and empire building. Only, what’s to stop the majors from horning in on the space, just as the likes of Paramount and MGM hoovered up first-run theatre chains in the 1920s to seize dominance?

For all that’s been proselytised by Web3 votaries about democratised access and dismantled monopolies, critics are leery of the reality that paper fortunes in cryptocurrency are currently held by an exclusive coterie of investors — thus reinforcing existing inequities. Yeo argues that decentralised systems will naturally hold sway over users who would assume multiple roles as “owner, advocate, contributor and participant.”

“Let’s say Facebook buys the entire landscape and chooses to centralise it. With Web3 being one that is open source, anyone can just copy the code, relaunch something new and decentralise it,” he explains.

Never mind that the recent crypto crash evaporated $2 trillion, calling into question the viability of platforms oiled by such volatile forces. Yeo contends that the crash has wiped out venal players “who came in for the wrong reasons”, thus paving the way for innovations of real value.

There’s a certain starry-eyed idealism underpinning this line of reasoning, one held up by faith in the public’s propensity to rally towards the common good. But if you consider the ever-present insidiousness of a digital cosmos wholly governed by tech giants such as Google and Meta, then an alternative paradigm becomes manifestly more appealing.

For Yeo, a consumer-driven metaverse (used interchangeably with the Web3 nomenclature) is a way to flip the script.

“In media, your value is based on how many visitors come to your website and your only monetisation model stems from sponsors. You may start off focusing on journalistic integrity, but over time because of stakeholders and advertisers you may be forced to write things in favour of your clients,” he reasons.

And he speaks from experience. “Even at EVOS we started off being hyper focused on doing the best for our fans but over time the incentives were misaligned because we were forced to change revenue streams for investors and hard sell because of brands. Generally, the end-users suffer from that,” he shares.

I wonder aloud whether Avium is born from disenchantment. “Of course,” he answers. “Naturally when you run a start up with VC funding your value is determined by how you change metrics, which are important, but outweigh the importance of being people-focused. Overtime entrepreneurs are forced into a corner doing things just to achieve a higher number but losing the whole purpose of running a business,” he asserts.

I suggest he may have felt jaded, a term at which he begins to protest before pausing to concur: “Yah, actually I was jaded, lah.”

Avium is Yeo’s blank canvas. Although in the early stages of corralling a community of regional collaborators to hash out the minutiae of intellectual property definitions, he’s convinced that where the rubber meets the road, it will be a win-win scenario.

Don’t forget that this is someone who built a multi-million-dollar company from a crudely rigged up gaming house for five athletes. This time, he’s turned his attentions to underrepresented creatives.

“I dream of a world where people can finally pursue what they want instead of following what society expects of them. I hope this world allows more things to be viable and for people to express themselves.”

Photography: Mun Kong

Styling: Chia Wei Choong

Hair & Makeup: Rick Yang/Artistry, assisted by Alycia Tan, using Shiseido and Keune