As we examine the casualties of Covid-19 in the rear-view mirror and gear up to restore an ailing planet, others elsewhere in the developing world stare down the barrel of immediate existential threats. Namely, the struggle to fulfil basic needs such as shelter and food.

It thus isn’t hard to fathom how pandemics and climate change would disproportionately affect the have-nots who drift in society’s periphery.

According to Bernard Heng, an international consultant working in contexts with hosts and refugees, such events exacerbate existing vulnerabilities for displaced communities.

“The pandemic has created challenges for persons with co-morbidities to access basic services safely. Children and the elderly now face additional risks in overcrowded conditions. In arid and semi-arid areas, climate change-induced uncertainty over rainfall creates challenging conditions for beneficiaries who live on already inadequate water access,” he says.

Beyond horizon-defying refugee settlements shunted to rural areas, the housing crisis festers amid urban blight. Exoduses from increasingly non-viable agricultural regions to cities largely triggered the latter. The World Bank estimates that the global housing shortage will affect 1.6 billion people by 2025.

Beyond the Drafting Board

Architectural designer Prasoon Kumar of BillionBricks thinks he may have found an elegant solution that addresses both systemic inequality and climate change. His locally headquartered social enterprise is about to launch its first Net-Zero Home in the Philippines.

If we want to impact a community at scale, we must change our approach and think from their perspective rather than what we think they need.

Prasoon Kumar, CEO of Billionbricks

Rigged with solar panels, each building can produce more energy than it consumes, allowing occupants to sell unused energy to the grid. They will cost around $30,000, and they will be financed by a government-backed loan scheme. It’s a considered approach to humanitarian architecture predicated on smart design and economics.

“Affordable housing is not financially attractive to (private investors) so governments often have to step in, but they are often corrupt or do not have the vision or means to disburse funds. How do we attract more capital into an area that needs it?” muses Prasoon.

The President’s Design awardee — who invented a weather-resilient emergency tent that was handily co-opted as quarantine facilities over the pandemic — sits with other humanitarian architects who apply design thinking to combat social pathologies, from education to healthcare.

Among his contemporaries is Trecia Lim of WeCreate Studio, an architectural and design consultancy conceived in 2007 that is building capacity in remote South-east Asian communities. In a dust-stippled hinterland straddling the Myanmar-Thailand border, the firm has completed a primary school for children of a South Karen hill tribe. The team is also looking to introduce vocational education programmes teaching mechanical and bamboo building skills to villagers.

The project has been an eye-opener for Lim, who financed the school’s construction with her savings and then saw her plans mothballed due to pandemic-related restrictions. “We no longer want to build the skin but the platform for education. We must look beyond architecture and collaborate with individuals of different expertise; we recently met education investors who are exploring new business models to fund and sustain the school,” she shares.

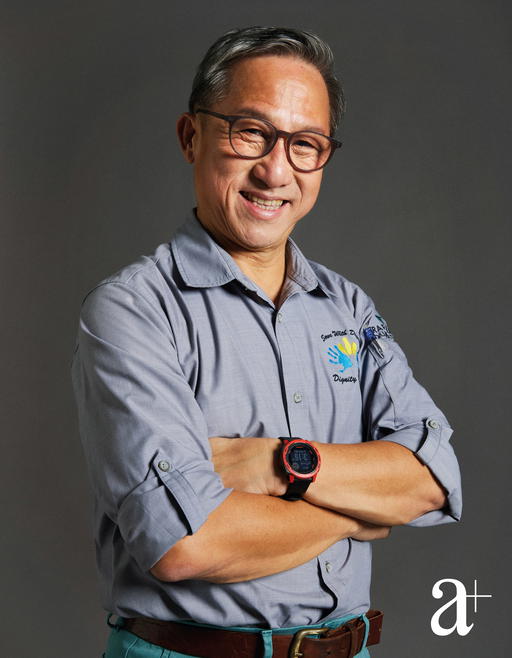

Humanitarian architecture, evidently, isn’t as cut and dry as plonking down brick and mortar. Rudy Taslim is acutely aware of this. He founded Genesis Architects together with his wife Lam Bao Yan after quitting his job in a large architecture firm and buying a one-way ticket to Africa. His time spent volunteering there compelled him to “rethink how I should practise as an architect and live as a human being.”

Photo: Genesis Architects.

Among the realities he could not unsee in Rwanda — still besieged by violent extremist attacks in the aftermath of the 1994 genocide — were malnourished child soldiers taking up arms in return for a meal and blind toddlers abandoned to fend for themselves in the mountains.

Marshalling resources from their firm’s commercial arm and clients with whom their cause resonates, the duo builds and sustains long-term projects such as a school for the blind in Rwanda that distributes daily meals, a 75-ha university in Mozambique, and an airstrip deep in Borneo’s jungle for medical evacuations.

Lam, who isn’t architecturally trained but has a background in business education, is the proverbial soul of the operation, pegging away at programmes to train teachers and improve the livelihoods of locals. For instance, her homespun pastoral initiative allows historically marginalised villagers to rotate stewardship of cows and goats for cultivation and nutrition. They’ve also established a brick factory that provides employment to locals. Like Lim of WeCreate Studio, their practice accounts for capacity building. They also facilitate knowledge transfer at their Rwanda outpost.

“Our position is that we should always help empower them so they will build their own countries and not just rely on foreign expertise or proprietary systems they may not have access to,” reasons Taslim, who incorporates IKEA-esque infographics when conveying construction plans to builders lacking formal training.

A Collaborative Approach

This isn’t to say their relationship with the locals is didactic. The earnest couple works closely on the ground with local leaders and organisations to get their buy-in. “The last thing we want is to act like we are better because, contextually and culturally, what works here rarely works there. As we entered their world, we felt what they felt, and we put on our thinking caps to figure out what local resources are available to us,” shares Taslim.

Kumar and Lim share this sentiment, seeking suggestions from their end-users to incorporate into their designs. The BillionBricks Net-Zero Home, for instance, will have its rooftop solar panels repositioned to be less conspicuous after residents in a nearby industrial area commented that the building looked like a factory.

“If we want to impact a community at scale, we must change our approach and think from their perspective rather than what we think they need. Architecture is often aspirational, and people may like buildings we might not like to design as our ethos is different,” explains Kumar. He adduces the example of typically costly double-storey homes that are favoured by Filipinos as a marker of privilege, as well as a practical feature in a country susceptible to flooding.

Photo: WeCreate Studio.

Co-creation also factors heavily in the work of Heng, who has involved refugees in participatory workshops harnessing 3D modelling and sketching exercises as part of his spatial planning process. “The outcome is a public space that is welcoming to different user groups, including play spaces for children, sports pitches for youths, game boards for men, and shaded resting spots for all — with users comfortable in each other’s presence,” he shares.

As well as gaining a bone-deep understanding of foreign folkways, humanitarian architects often find their fundamental understanding of design upended — usually due to impecunious circumstances. “The Karen villagers asked me why we bought so many metal rods for rebars (reinforcing bars). They substitute the bars with bamboo. That makes sense as bamboo has good tensile strength,” says Lim.

For the construction of primary schools in Congo, where hauling bricks through rough terrain is costly, Taslim tipped volcanic rock gathered from the surroundings into cages wrought from metal wire. Buildings are also designed to be climate-responsive, with factors such as their orientation assuming paramount importance in the absence of air-conditioning.

In order for design to solve problems we need time and engagement with its ultimate users; once you understand their needs you can appropriate something that suits them. With this understanding, good design can meet both social and environmental needs.

Trecia Lim, WeCreate Studio

Likewise, Genesis’ interior designs adhere to vernacular architecture principles, which aim to bring dignity back to people by invoking culturally relevant spaces.

“We try to introduce metaphors in the schools we design. For example, in the university in Mozambique, we drew references from local culture through the geometric Capulana fabric. We imagined the institution as a place where people would study to be part of a more effective fabric of society,” illustrates Taslim.

Admittedly, resourcefulness and adaptability outweigh aesthetic perfection when you are working amid entropy. Taslim and Lam recently aided rebuilding efforts in war-torn Ukraine and are planning on repurposing an abandoned school in East Germany into a refugee centre.

“A crisis is not a full-dress rehearsal; we have to think on our feet and solve problems on the go. When I visit places like that, I can’t just wear my architect’s hat as I may be required to cook or take care of children. You are part of a collective body to help people,” he asserts.

In a world where conceptually challenging buildings plumed with superlatives has become shorthand for winning architecture, the comparatively utilitarian buildings rising from penury may pale in comparison. Yet, as these professionals have shown, thoughtfully conceived community projects can be a tour de force in transforming lives.

Lim sums it up neatly. “In order for design to solve problems, we need time and engagement with its ultimate users; once you understand their needs you can appropriate something that suits them. With this understanding, good design can meet both social and environmental needs.”

Population On Edge

- 163 million more are living on less than $5.50 a day because of Covid-19. That’s over 4 times the size of Canada.

- One-third of the world’s internally displaced people live in the 10 countries most at-risk to COVID-19.

- Climate change will see at least one billion people at risk of losing their homes to storms supercharged by rising seas by 2050.

- 60 per cent of the urban population insub-Saharan Africa lives in informal settlements, exposing them tourban vulnerability.