On 8 September 2016, a 17-year-old girl from the slums of Mumbai become the world’s first acid attack survivor to walk New York Fashion Week. She represented not just herself, but the most abused section of society in India — women attacked with acid and burnt with kerosene in violent vengeance from scorned lovers, jealous husbands or ashamed fathers. She was a symbol of hope to every acid attack survivor that my organisation rehabilitates, and many others we haven’t yet reached.

In India, a woman is attacked with acid on a daily basis. In India, a woman is burnt every 90 minutes. These are just the reported numbers. The actual numbers are hidden away under red tape, due to a corrupt system and complacency from local officials.

But why would someone do such things to a woman, you may ask. After all, acid burns through metal. Can you imagine what it does to flesh and bone? It rips away features, blinds, deafens and deforms. It steals a person’s identity to a point that in Indian burn wards, hospitals refuse to keep mirrors.

And that is where the problem lies. We live in a society where a person’s identity is assumed to be etched on their face. In India, a woman is complimented on how pretty or thin she is, or how lovely her hair is. Kindness, gentleness, intelligence, courage — those come second.

I run a non-profit called Make Love Not Scars that rehabilitates acid attack survivors from all walks of life. In 2014, we established India’s first rehabilitation centre for acid attack survivors in New Delhi. Initially, we only funded life-saving and reconstructive surgeries. Survivors would come live at our centre to recover, post-op, under the care of nurses.

Soon, we realised that they had nowhere to go. Most were attacked by family members, after all. We offered therapy and emotional support to help manage their trauma. We started giving them an education, funding skill training lessons and went so far as to pay for transport back and forth from classes because we wanted nothing to stand in the way of their education.

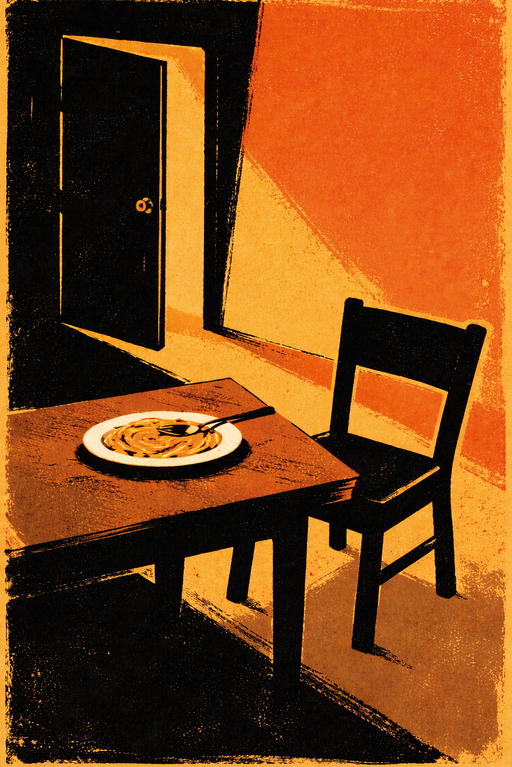

But that was when we noticed little red flags. Every survivor leaving our shelter home would cover her face. When we asked why, they said it was because people stared and pointed and pulled away their kids. “Our faces scare them”, they said. That didn’t go down well with me or my team. Our survivors’ faces are just that — faces. Nothing to be scared of. Then we hit more roadblocks. Employers offered to hire them, just not in customer facing roles.

Is that the value of beauty in our society? Is beauty a benchmark for us to assess who deserves to be in mainstream society?

If injustice exists, it must be pointed out. It must be changed. And the only way to do that is to change the very system that propels it.

Modern beauty standards are forced down our throats through television, fashion, and the world of glamour. While all of these things are enjoyable and add joy to our lives, they sometimes cross a fine line. We tried reaching out to multiple fashion houses in India to represent survivors. Despite their fears, survivors came forward, wanting to propel change. Each one was willing to represent her people, uncovering her face on the world stage. Though the camaraderie back then was unlike any I had seen, nothing worked out — until New York, where Reshma Qureshi was chosen to represent our cause.

That fashion show changed how Indians viewed acid attack survivors. It made global headlines. Indian fashion and media houses reached out, wanting to place acid attack survivors as showstoppers in glamorous shows and features on the front page. In 2017, Make Love Not Scars organised a fashion show solely featuring survivors, with India’s leading designers — including Ranna Gill, Rohit Bal, and Archana Kochhar — donating their outfits to be worn by them. Show proceeds benefitted survivors. Soon after, we noticed that survivors were now walking out of our doors with their faces uncovered.

The world of glamour is not just ‘frivolous’. It can be a breeding ground for toxicity and false realities. On the flip side, it can be the very harbinger of change and inspiration that we might just need in our lives.

Today, our survivors embody glamour, making the best of their circumstances with more grace than I could ever hope to have. They design their own clothes, experiment with makeup, take care of themselves — scars and all — and walk out of the door with their heads held high and scarves forgotten because after all, beauty sometimes comes from that very thing that we can’t exactly place a finger on — the human spirit.