There’s a defining scene in the film Baby Queen where a bare-faced Opera Tang lies draped over the lap of her 90-year-old grandmother, who glisters in resplendently voluptuous drag makeup as a samsui woman of yore. Reverberating beneath the nonagenarian’s visually arresting metamorphosis in the likeness of her drag queen grandson, is a deftly delivered gut punch that lands as—tenderly stroking her hair—she muses aloud over whether she will live to see her get married.

It’s an achingly poignant moment immortalising the pair’s ineffably close relationship transcendent of age, time and societal norms.

“That scene resonated with a lot of people because they have someone in the family who may be their biggest supporter giving them unconditional love. It was very important because the underlying message is that queer people are not excluded from the family unit and goes against the argument that we need to protect families through institutional marriage,” says Tang, the documentary’s queer protagonist in reference to opposition to Section 377A’s repeal.

Directed by Lei Yuan Bin, Baby Queen recently premiered at the Singapore International Film Festival 2022 and the 27th Busan International Film Festival respectively. There’s the air of an ingenue in the doe-eyed Tang, as she effuses about walking the red carpet at the latter, where she says she met a chiselling of Korean celebrities.

“I was very proud to represent my country, especially the queer folk and drag community, in a foreign setting. If someone puts a gun to my head and shoots me now, I think it would be fine as I already feel very accomplished,” she jokes of her Warholian moment.

Tang herself is something of an arriviste, having debuted at Pink Dot 2020 and appearing in the landmark LGBTQ+ video the subsequent year. It placed her on Lei’s radar, thus setting the film’s premise of a drag queen whose star is on the rise. “There were a lot of mixed emotions within the drag community; why is this opportunity given to a new queen who hasn’t done anything. But it is not about how many years you’ve been doing drag but the things you stand for and perhaps I represented the Chinese cultural queens,” reveals the 27-year-old, further venturing that the younger generation of drag queens tend to be less hierarchical than previous ones.

As a young, emerging artiste occupying the hyperbolic cosmos of big hair, brassy personalities and caustic humour, the account manager at a Canada-based digital marketing agency by day appears to be comparatively unassuming—mild-mannered even. For one, she adamantly refuses to spill the tea on the scene’s inevitable drama, pleading that “the community is so small this will come and bite me in the ass tomorrow.”

She has, however, observed a preponderance of Malay over Chinese drag queens in the country. “I wanted to do my Master’s thesis on this—I wondered whether it is because ethnically Malay people are more creative or Chinese people are more inclined to toxic masculinity that they don’t want to do drag. I would think there are many socio-economic reasons that may explain this phenomenon,” she infers, revealing that the cerebral and camp can rest comfortably on the same plane.

The slow-burn inertia of the pandemic—that at one point triggered an 80 per cent pay cut—led her to saunter into Singapore’s drag scene, albeit cautiously.

“On the way to the first photoshoot at Redhill MRT I was clad head to toe in pink and shivering in the car, my best friend from secondary school took pictures on her iPhone and we posted them. It was very ‘chupalang’ (haphazard) and in the heat of the moment but thankfully no one snatched my wig or called me names,” recalls the longstanding fan of RuPaul’s Drag Race.

Her coming-of-age and -out journey, which the film addresses, is distinctly less serendipitous. “Coming out took a long time for me because I was raised a cradle Catholic so there’s still a lot of Catholic guilt I’m trying to unpack. Growing up I had so much hate and negativity around this part of my life that I shunned it and was so in denial that I only came to terms with it during my rebellious teenage years,” she admits.

As a junior college student, Tang attended her first Pink Dot rally in defiance of her staunchly Catholic parents, a decision that abruptly jerked her out of the metaphorical closet. “I was 16 or 17 and very vulnerable, with just a towel around my waist as I had just come out of the toilet. My mom showed me the newspaper with Pink Dot in the headlines, asking if I had attended it and was homosexual,” she recounts.

Perhaps unsurprisingly—but nonetheless unnervingly—her subsequent confession was met by palpable turmoil especially from her father, a former high-ranking army officer. “It came down to, ‘I’m disappointed in you, get out of my sight.’ I really thought he hated me at that time, so I just broke down and went into my room.”

Though the initial trauma was later resolved with what Tang describes as an awkward hug, she adds that her family still isn’t fully at ease with her more flamboyant proclivities. They may maintain a modus vivendi, but she’s grateful for them sponsoring her tertiary education.

“My mom didn’t really come to terms with me doing drag until she saw me in full costume, hair and makeup and helped me do the back button of my cheongsam,” she recalls, gesturing to fan away welled up emotions. Perhaps more telling of their implicit acceptance, is the fact that they all attended Baby Queen’s Singapore premiere.

Tang’s relationship with her grandmother, who plays a pivotal role in the film, is decidedly less complicated. She gets her sartorial savvy from the former seamstress, who painstakingly sews most of her costumes.

“When I was a kid, she made this beautiful white satin wedding dress for my barbie doll I loved so much that had Velcro at the back, puffed sleeves, a long train and gathering at the waist. I loved playing with barbies and she didn’t mind; it was the male members in my family who were kind of irked by me,” she shares. The freelance decorative headgear designer has been bestowed with the matriarch’s 70-year-old Singer sewing machine. Incidentally—and perhaps, fittingly—her grandmother’s drag makeup for the film was done by her.

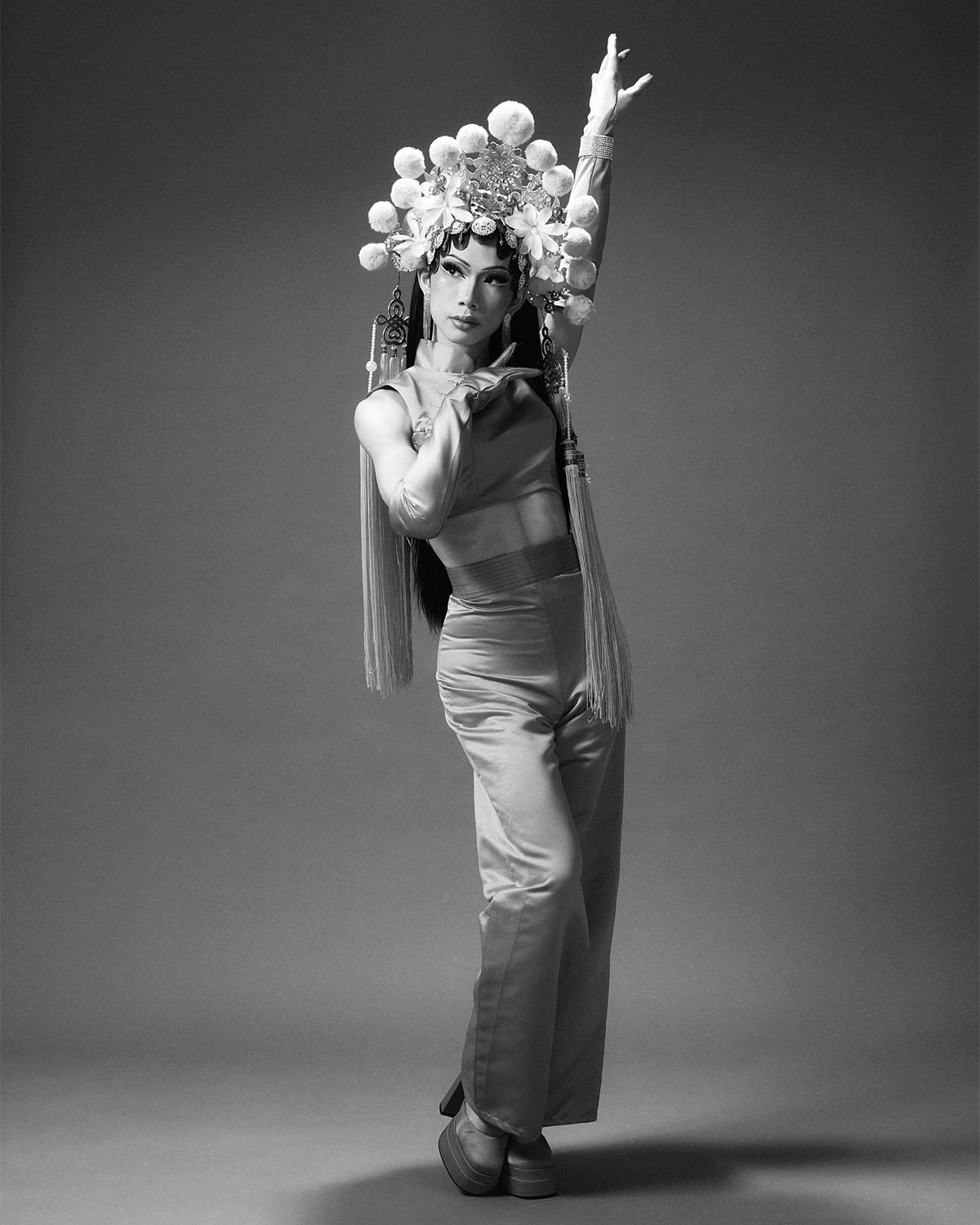

Opera Tang, whose grace notes are Chinese opera-inspired makeup, cheongsam and fastidiously embellished headpieces, is the manifestation of her patrimony. “I didn’t do well in Chinese class and took pride, shamefully, in not knowing the language and my culture. Opera Tang is a letter to myself to compensate for all those years I was stupid to not be proud of my culture and heritage,” she suggests.

Years of instruction in classical Chinese dance as a child comes through in the spare performer’s supple movements and easy gait. She draws upon traditional themes and motifs for her intricate headdresses, such as a phoenix coronet common to Chinese opera that’s embellished with 3,000 rhinestones. The documentary about her life isn’t built on filmy aesthetics though.

While Netflix’s zeitgeisty hit series Pose highlighted issues such as violence, discrimination and HIV that roiled New York’s transgender community in the 1980s, Tang hopes that audiences of Baby Queen will come away with the message that “queer people can be loved by their families and don’t always have to be problematic.” She’s optimistic that the repeal of Section 377A will normalise queer people and their relationships.

She aspires to eventually study Singapore’s drag community for her Master’s degree, in filtering the scene through an anthropological prism. “When I present my thesis, I will be clad head to toe in full drag regalia,” she quips. And just like that, with our interview wrapped up, she saunters off, limber and deer-like into a light drizzle.

Photography: Mun Kong

Styling: Chia Wei Choong

Photography Assistant: Hizuan Zailani