Spanish surrealist artist Salvador Dalí is celebrated for his strikingly bizarre works, from melting clocks in ‘The Persistence of Memory’ (1931) to the sensual grotesque of ‘The Great Masturbator’ (1929).

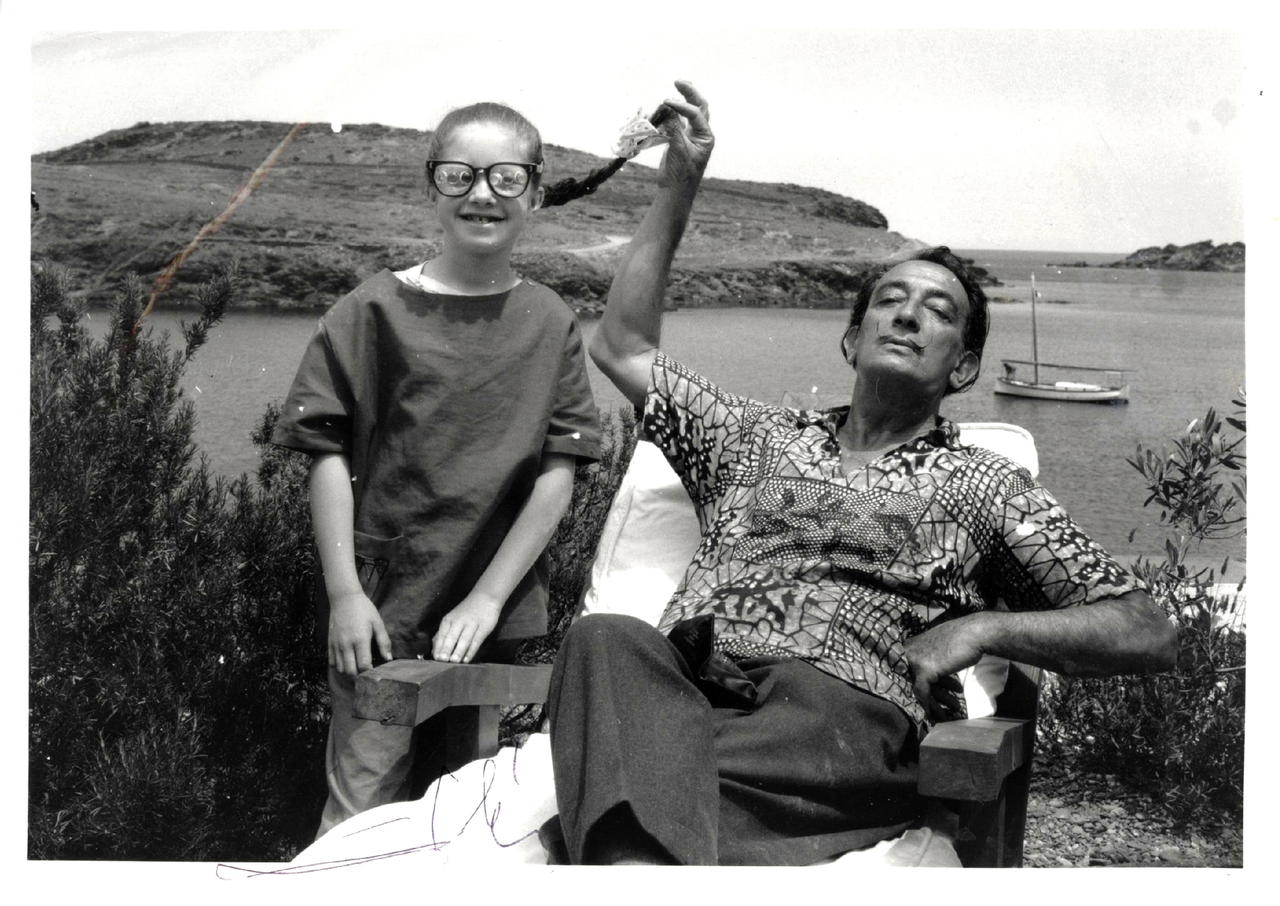

To Christine Argillet, however, he was “full of energy, humour, and spontaneity”. The daughter of Pierre Argillet, Dalí’s publisher and confidant, she first met the artist when she was five or six years old.

Her earliest memory of him dates back to 1969, when he visited her family’s home near Paris. Upon being shown a Sony video camera—a bulky, unfamiliar device at the time—he was immediately captivated and began dancing across the lawn, disappearing behind a tree, and then reappearing in front of the camera.

“He was playful, curious, and completely immersed in the moment,” she recalls fondly. “That combination of theatricality and inventiveness is what made him so remarkable as a person and as an artist.”

Her father met Dalí during a period when publishers focused on abstract art, so his work went overlooked. Mutual respect was evident from the beginning, however. “My father admired Dalí’s creativity, and he valued my father’s honesty. If my father felt a work was not quite right, Dalí would say, ‘I know, it is not for you. I will create a better one’.”

Their collaboration was characterised by trust and openness. They also worked at a similar pace. Dalí had a lot of ideas and needed to move quickly. Her father provided plates, tools, and support right away, so the unorthodox genius could continue to do what he was doing. Their partnership endured because of their friendship and respect.

Argillet is the curator and custodian of the Argillet Collection, created through her father’s close collaboration with Dalí. Presented by Bruno Gallery in Tanglin Road from 26 September to 30 November, “Dali Comes to Singapore” featured more than 100 original etchings and gouaches from this collection.

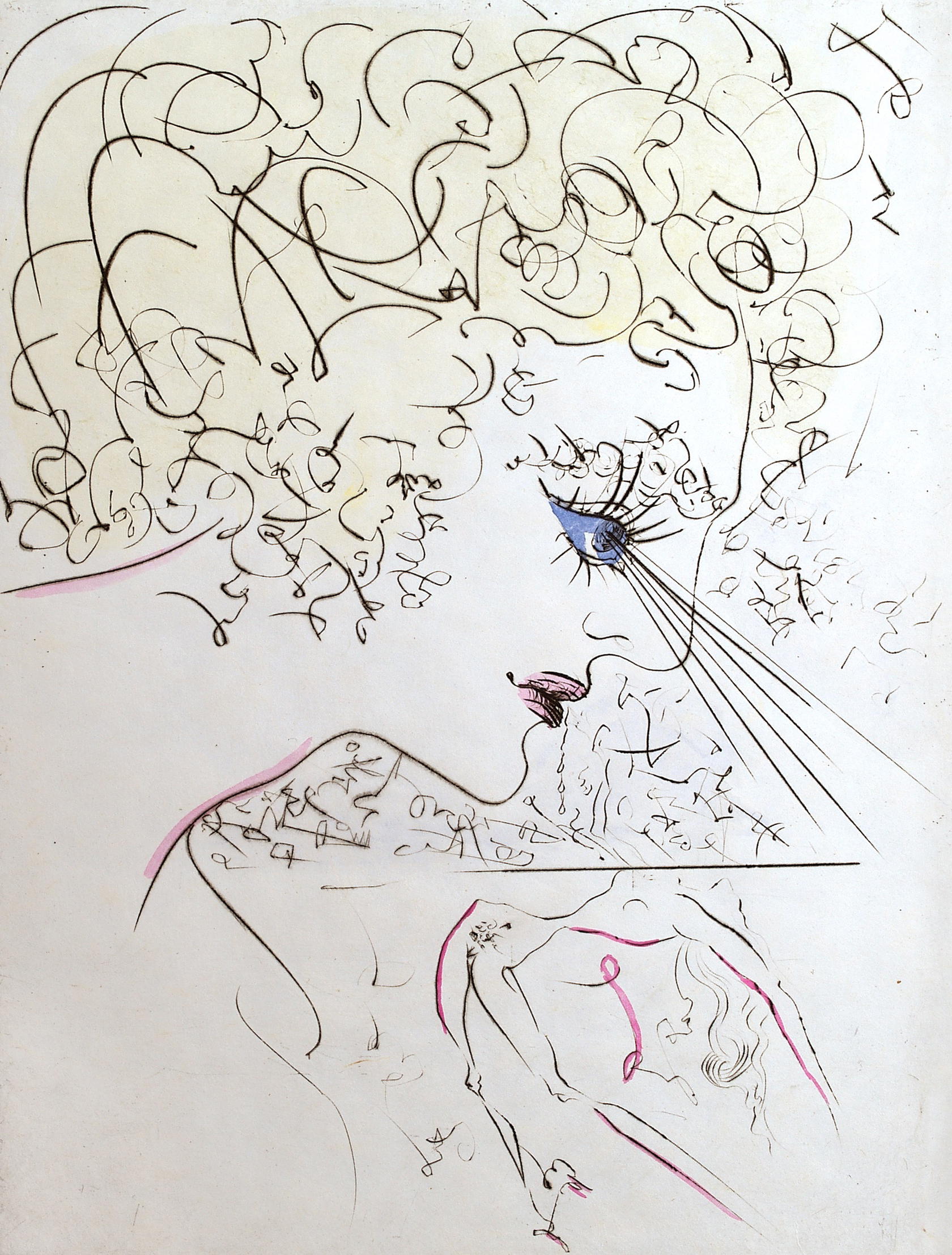

Highlights included ‘Flower Women at the Piano’ (1969) from Dalí’s The Hippies Suite, which depicted surreal, flower-headed figures at a grand piano. In addition, the artist’s fascination with alchemy and the subconscious mind was evident in ‘Old Faust’ (1968–1969).

The Argillet Collection represented Dalís artistic vision in a manner that cannot be found in major institutional holdings, covering a range of themes from mythology to literature to dream imagery, adds Argillet.

It was evident in every one of his works that he combined both meticulous skill with an irrepressible imagination. Furthermore, the exhibition highlighted the extraordinary three-decade friendship and creative exchange between Dalí and the Argillet family.

While most know Salvador Dalí for his paintings, “Dali Comes to Singapore” focused on his etchings and gouaches in which he used opaque pigments ground in water and thickened with a gluelike substance.

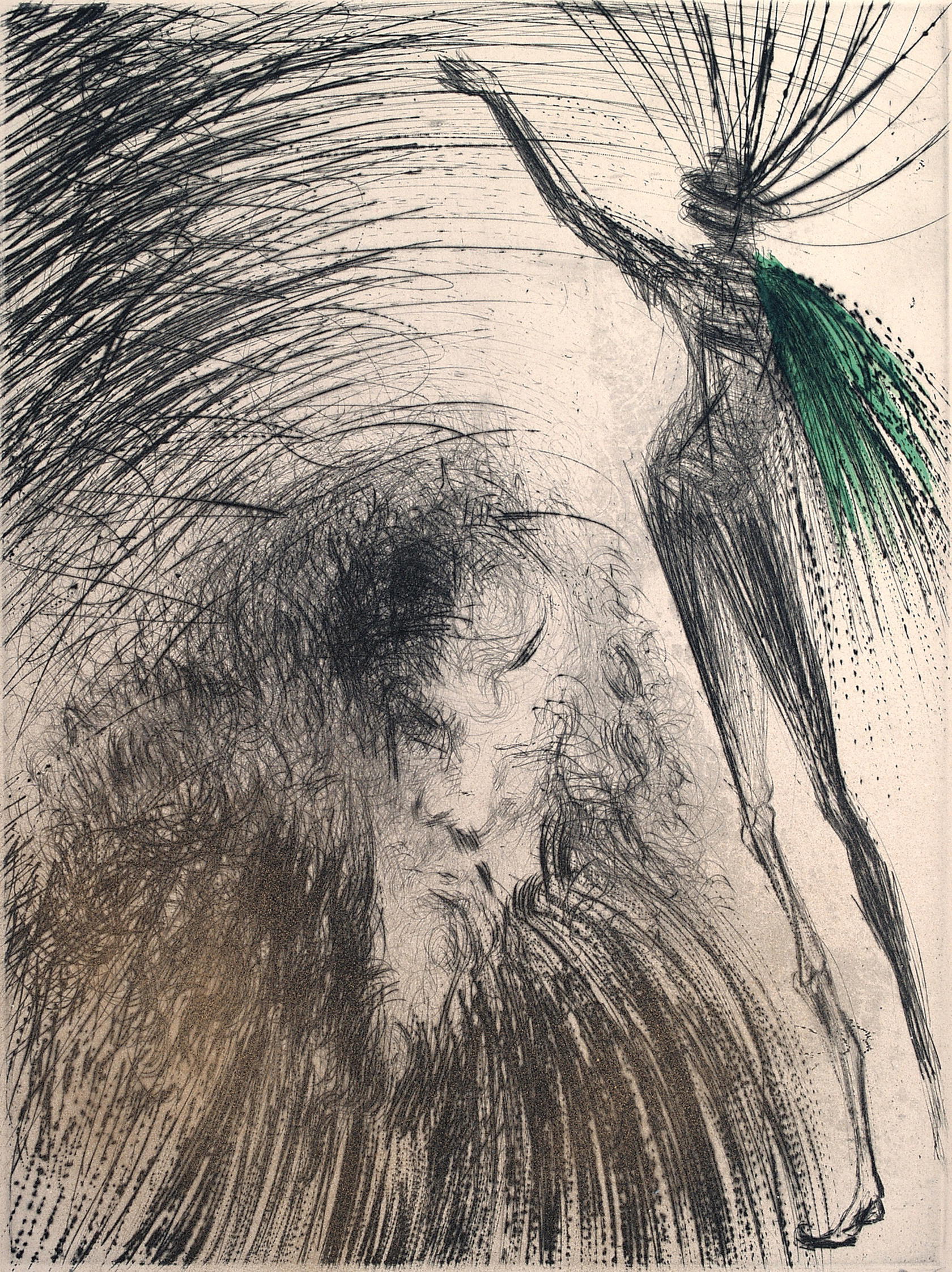

In Argillet’s opinion, these mediums allowed the eccentric artist to explore techniques and materials in a way that painting alone could not. Incorporating other unconventional techniques, such as acid-soaked octopus imprints or precious stones as engraving tools as well, he conveyed a sense of playfulness and innovation. These revealed not only a deeper understanding of his creative process, but also a constant desire to push the boundaries of artistic expression.

Argillet notes that she was particularly struck by ‘Medusa’ (1963), an etching based on the Greek myth. Finding a dead octopus on the shore, Dalí used it to imprint the copper plate, turning raw biology into an image of the Gorgon. The piece neatly fuses the literal and the mythic, emblematic of his inventive bent.

Singapore was a natural choice for the exhibition, she says. Dalí was fascinated with the East, despite never travelling beyond Greece. “He imagined these places in his mind Presenting the collection here gave audiences the opportunity to experience his vision through a fresh perspective.”

Intrigued by how people would react to and interpret Dalí’s works, she also felt Singapore would provide a unique cultural lens for this dialogue. “As well as seeing his works in new places, he loved surprises. Even though Singapore may not have been what he expected, but he would have welcomed it with much joy and curiosity,” Argillet concludes.