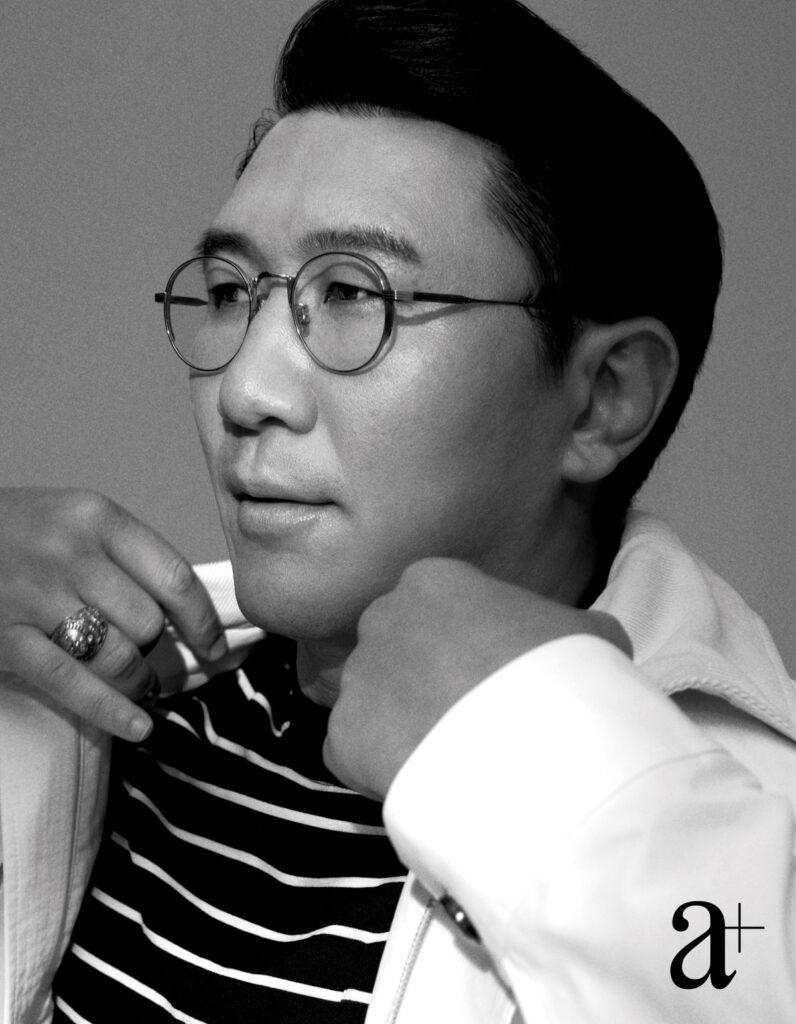

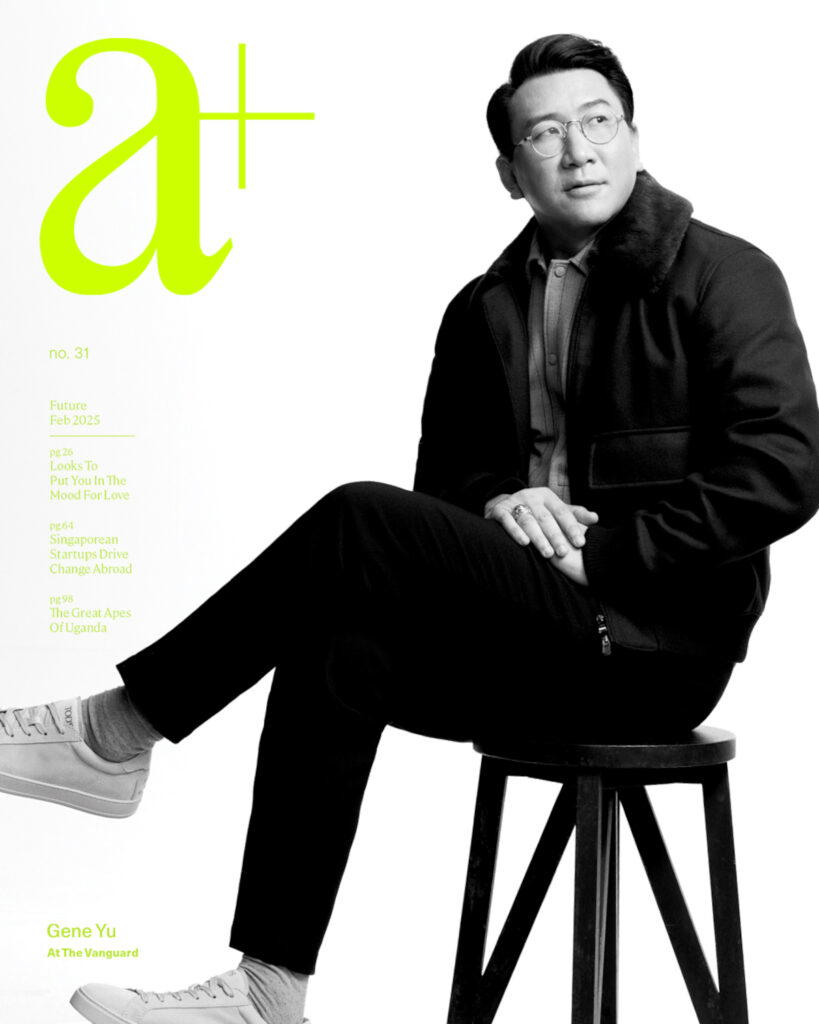

They say never negotiate with terrorists. But even as a former US Army Special Forces officer who carried out hostage rescue missions in Iraq and Baghdad, Gene Yu recommends working out a deal.

“l mean, I used to drink the Kool-Aid. America doesn’t negotiate with terrorists, right? We see it all the time in movies,” he says. “But that’s easy to say when it’s not your interests on the line. What other options do you have at that point when you’ve been checkmated? You have to negotiate.”

Yu’s story has been widely covered. A quick Google search will pull up several articles and video interviews about both his time in the US military and his involvement in the unsanctioned rescue of Evelyn Chang, a Taiwanese citizen abducted by Abu Sayyaf gunmen in 2013. Details of the incident have also been released in his new book The Second Shot: A Green Beret’s Last Mission.

The first thing to do when negotiating, he adds, is to ask for proof of life. As with any trade or transaction, ascertain that the other party has the goods before making payment. “In the case of a kidnapping. I want to see that they have not been mutilated or maimed in any way. Because if, say, their hand has been cut off, I’m not paying full price. It’s an immediate negotiation factor.”

Now, the 45-year-old is Founder and CEO of cyber emergency response firm Blackpanda, which is headquartered in Singapore and counts Singtel as an investor.

He draws a parallel between dealing with terrorists and ransomware. “Similarly, it’s easy to say ‘Don’t negotiate with cyber criminals’ or ‘Just band together and crowdsource a solution’ when it’s not your sweat and blood that went into the company.”

Despite the many death-defying situations he has been in, Yu believes that running a company is the hardest thing he has ever had to do. “My Blackpanda journey is crazier than anything I’ve ever done. I’d unequivocally say that being a special forces team leader is vastly easier than being a tech founder here in Asia.”

Yu’s parents grew up on the breadline in Taiwan, so they left for America in search of a better life. The family put down roots in Cupertino, a city in California’s Silicon Valley, where his father at one point worked as a vice president at Nvidia.

In his book, Yu wrote that his mother’s “Asian instincts began kicking in” when he was in middle school and she started “tightening the reins”. But the tone in the writing is something he regrets, he clarifies from across the table. “Writing a book with a major publisher means there is a lot of influence from a large team of editors and writers. They change the tone of things. They tell you, ‘This is what readers want to hear’.”

He recalls his mother driving four hours on weekends to ferry him to and from tennis tournaments and his father picking up baseball so they could play together. “My parents were quite liberal, which was exactly why I had a strong sports upbringing.”

Rebelliousness, however, set in in his adolescence due to the pressure from being in a hyper-competitive school environment and the vexation of navigating life as an Asian American. Teenage Yu sported long hair and a trench coach, and constantly shoplifted books. “I love reading. The stealing just came from a position of the ridiculous attitude of, ‘Knowledge should be free’. I was a very entitled punk.”

Petty theft would alter his life. After perusing a shoplifted copy of Honor and Duty by Gus Lee, a novel that depicts a Chinese American’s experience at West Point in the 1960s, Yu became obsessed with the prestigious American military academy even though he assumed it was fictional.

“There was no internet back then, so I thought it was a made-up school. It was like reading Hogwarts for Warriors,” he analogises. “Still, I was like, ‘This place sounds amazing. I wish it were real’.”

Hence his bewilderment when he received a recruitment letter from West Point a couple of months later. American military academies tend to scout potential recruits at sports tournaments and Yu had been a prominent tennis player. Although his parents took a dim view of him being a soldier, he was bent on enrolling.

“West Point is the most hardcore educational institution in the world in terms of what it takes to graduate. You must be in top form academically, militarily, and physically. I didn’t like the stereotype of the weak, passive, and puny Asian male in America. As I look back now, I was attaching myself to a much larger brand to overcome it.”

Overcoming a stereotype

Yu’s enthusiasm was however quickly extinguished when he became a target of hazing in his first year. It didn’t help that he often fumbled orders. Among his onerous tasks was to memorise the number of ice cubes each of the upperclassmen at his table wanted and the size they wanted the cubes to be; they came in three sizes. A single slipup guaranteed beration.

“I don’t have any nightmares about my time in combat, but I have recurring nightmares of being a plebe, covered in cold sweat, getting screamed at for hours on end,” he says.

He pursued a degree in computer science during the four-year course. Months after graduation, the 9/11 attacks happened, an event he says was perhaps foreshadowed at his Acceptance Day parade. ‘The superstition is that if it rains on your Acceptance Day parade, you’re going to war. It wasn’t just heavy showers, but also a lightning storm,” he recounts. It is why the symbol on the crest of his class ring is that of a lightning bolt. He is wearing the ring in this cover story.

After a stint in Fort Knox, Kentucky as a tank officer, he tried out for Ranger School, a famously rigorous US Army small unit tactics and leadership course. Eighty-eight lieutenants showed up on Day One, 16 made it to the end of the selection process, and Yu was the only one who graduated without having to repeat the course.

Nonetheless, the experience was pure hell. “Every morning now, when I take a moment to think about the things I’m grateful for, I think to myself, ‘I’m grateful I’m not at Ranger School’,” he says with a chuckle.

Following a stint at the Korean Demilitarised Zone for two years, Yu enrolled in the US Army Special Forces Qualification Course. It was during this time that he committed an infraction that has been used as a cautionary tale to new students: amid a segment of the programme in which he was expected to live off the land, he left the boundaries to procure pizza. The furtive excursion only came to light because he had failed to discard the receipt.

Yu was expelled one day before graduation. Still, he’s in two minds about whether he would have done anything differently. “Half the people thought I was being creative while the other half just did not take to it. I’ve had strangers come up to me and say, ‘You’re the biggest piece of shit officer’.”

“So, would I have done it again? Definitely not if I know I’m going to get caught. But I’ll be honest, if I won’t be, sure. It was a target of opportunity and I took it.”

Gene Yu looks back on a controversial move

Providentially, the Chief of Staff of Special Operations Command in South Korea at that time had taken a shine to Yu, so he was allowed to repeat the class and eventually received his Green Beret.

He however reckons that the pizza incident actually changed his career track for the better. “Because I had to do it over, I ended up having one of the widest ranges of combat missions of a special forces captain. I truly believe those missions were one of the reasons I was selected for early promotion,” he says. It was during those operations that he carried out hostage rescue missions in Iraq and Baghdad .

After 12 years in the military, Yu left to pursue a corporate career, working for conglomerates like Credit Suisse and Palantir. In 2013, he led the rescue of Evelyn Chang in the Philippines by engaging contacts in the Filipino armed forces and a network of private security contractors. Chang was a family friend and his mother had asked him to see if he could help.

The full story is detailed in The Second Shot, which he says he agreed to write to shine a spotlight on the other heroes who helped execute the mission. “They’d just met me, but were willing to put their lives and careers on the line to help save a woman they’d never met. In fact, those in the military also put their freedom on the line because they could have been court-martialled for participating,” he underscores. “It is why all the payment for the book went to them.”

DIVERSIFYING CYBERCRIME risks

Yu had been struggling in the startup space in Hong Kong when his friend and mentor Matt Pecot proposed incorporating a physical security company using ex-special forces members. “He said, ‘Nobody is doing this in Asia. I’ll give you a million dollars to do it’,” Yu recounts. “I was like, ‘Done’. Who gets to start a company with that kind of money?”

The duo co-founded Blackpanda in 2015 in Hong Kong. The company’s first few jobs involved strategic security consulting contracts for large infrastructure projects like gold mines and energy power plants in the jungles of the Philippines. Yu and his team were engaged as strategic security consultants as the area was rife with rebels, bandits, and terrorists.

Although lucrative, the work was perilous, so he began to wonder if his efforts were prudent. “As a soldier, it made sense to put my life at risk because I believed in the US Constitution and could get behind the mission, but I’m not going to do it just for a little bit of cash.”

When Resorts World Manila was attacked in 2017, Blackpanda was called in to help restore security. A week later, the entertainment complex was also hit by a cyberattack, and Yu asked if he could have a crack at solving the problem. The job made the company comparatively more money and highlighted the growth of digital threats, so Blackpanda pivoted to cybersecurity. It moved its base to Singapore in 2020 when geopolitical headwinds threatened instability.

Although the company’s strategy has changed five times since its founding, it now focuses on cyber insurance, which shoulders a business’s liability for a data breach or cyberattack. Yu likens it to the model in which physical emergency responders like the police, paramedics, and firefighters are financed. “As a society, we all help pay to get someone an emergency response, and that is possible through tax,” he illustrates.

Insurance is the private sector’s version of that, he continues, as everybody pays a premium to manage the unfortunate events that occur to a small group.

“It’s essentially a diversification of risk. If you just walk through our door, we’ll bill you US$500 (S$677) an hour for our services, which means it might cost you anything between US$20,000 and US$50,000 to fix your issue. But if you pay the monthly premium for our subscription, we take care of everything if you get hacked,” he explains.

In the last two years, Blackpanda has seen 10 cyberattacks across the region, most of which occurred in Hong Kong and Singapore. The average amount the victims paid for assistance was US$625.

“People ask, ‘Gene, how could you possibly do all that for US$625?’. But I didn’t—it was paid for by the money the 1,500 companies pooled together.”

Gene Yu on cyber insurance

Yu wants companies to understand that cybersecurity is a security problem, not an IT problem. As it is, a cyberattack is carried out by a person, not a computer script; the invasion just happens to be through the digital terrain. “It’s the same type of criminal that thinks, I’m going to make money by kidnapping your family’. Yet, many companies think it’s an IT problem, so they leave cybersecurity to the IT people and blame them when there’s a hack. I find it insulting when people won’t invest in protecting their systems.”

His time in the military has been “vastly easier” than his entrepreneurial journey for several reasons. For one, startup founders in Asia aren’t given room to fail. “Here, if you make series A and then fail, which happens to over 90 percent of startups, you’re branded a failure,” he says solemnly.

ln addition, investors in Asia are risk-averse. “People here aren’t willing to finance anything that could fail. But if you don’t have the spirit and the guts to go out and fail, you’ll never push the envelope in innovation.”

Undercapitalisation, too, resulted in rash decisions in a bid to keep the company afloat. “We almost ran out of money more times than I can count. We just make sure to keep getting back up on our feet,” Yu says.

But his decade-long resilience is beginning to pay off. Blackpanda’s cyber insurance subscription has been growing 215 percent year on year. The company has 45 staff across four offices in Singapore, Hong Kong, Tokyo, and Manila, and will soon open a branch in San Francisco. Plans to expand into Australia this year are in the pipeline.

A partnership between the Singapore Police Force and Cyber Security Agency of Singapore sees the company providing anonymised data reports on local cybercrime. “The government needs to understand exactly what type of cybercrime is being carried out and the extent of the damage to allocate the necessary budget to solving the problem. As digital forensic experts, it is on us to validate the numbers.”

In spite of his extraordinary exploits, Yu is unsure if his story deserves this much attention even though Temple Hill Entertainment—the American film and television production company behind movies like Twilight, The Fault in Our Stars, and First Man—has approached him to adapt his book for the big screen. Simu Liu is in talks to take on the lead role.

Yu considers many key moments of his life to have been serendipitous. Had he not shoplifted a copy of Honor and Duty, it is unlikely that he would have heard about West Point, enlisted in the military, organised specific combat missions or acquired the skills necessary to lead Chang’s rescue.

This makes him regularly ponder how much control we actually have over our lives.”It’s one of the reasons why I enjoy being in crisis response. We may not be able to control the things that happen to us, but we can control how we respond,” he says.

No matter how unexpected the complications that arise, he never lets fear get in the way. The key to overcoming it, he says, is to be explicit about your desired end state and repeatedly do what is needed to get there.

“Training yourself over and over enhances confidence and muscle memory, which helps you push through the emotion. You might still feel scared, but you’ll be able to handle it better,” he affirms.

“The greatest fear is of the unknown, right? It’s why we’re, say, afraid of the dark. But if we practise walking in the dark every night, we’re going to be less afraid. The answer to conquering fear is rigorous training to mastery.”

For more inspiring stories in a+ all year round, gift yourself or loved ones a digital subscription.

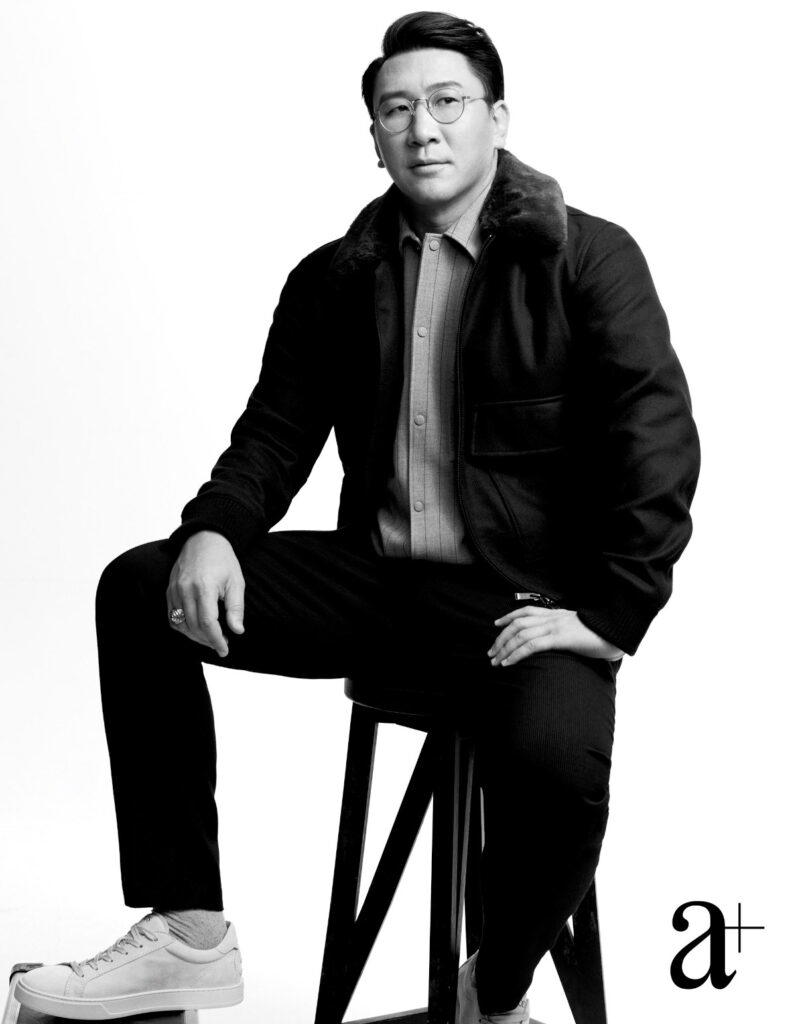

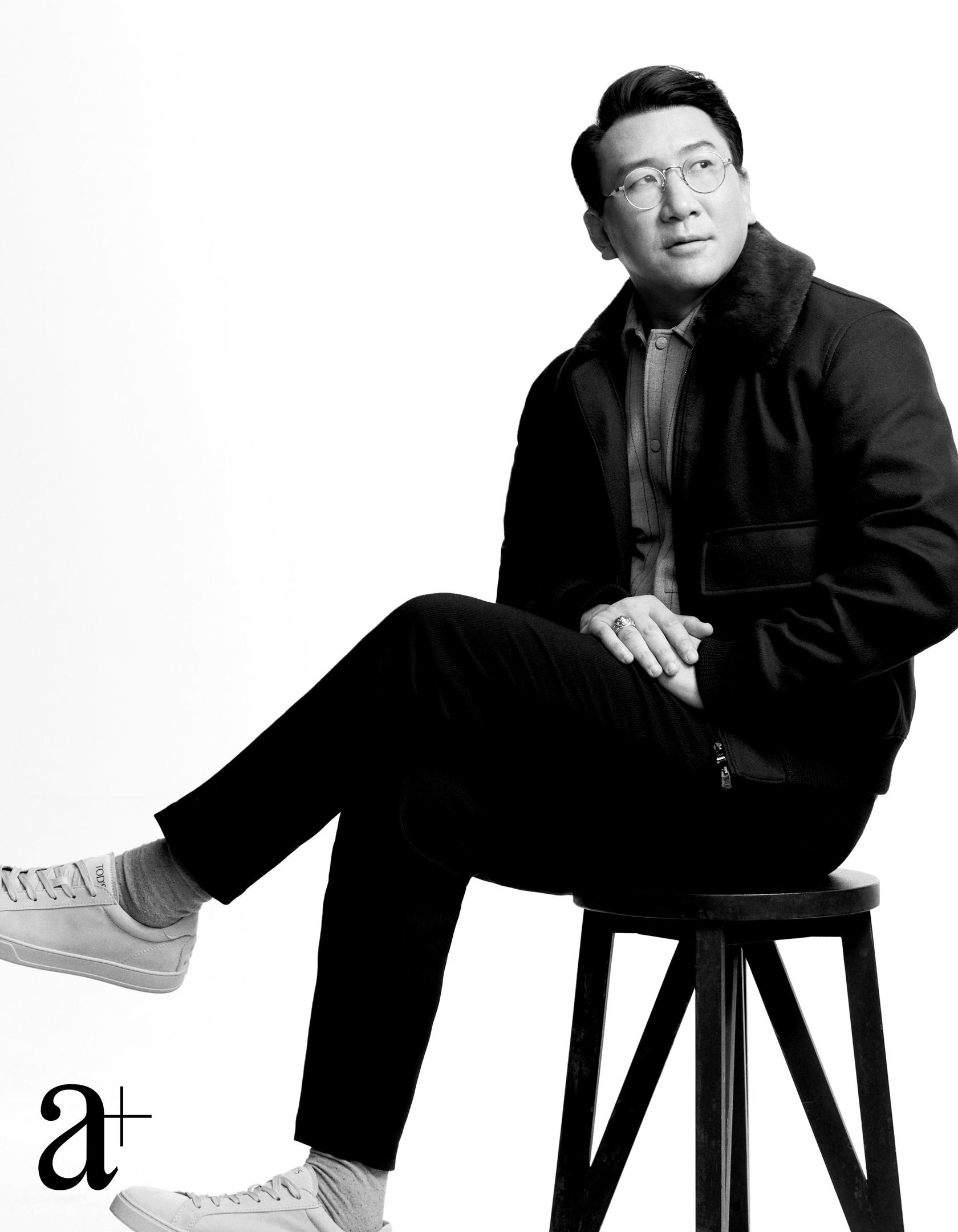

Photography Joel Low

Styling Chia Wei Choong

Grooming Wee Ming using Chanel beauty & Schwarzkopf Professional

Photography assistant Eddie Teo