On a cool, rain-slicked November morning in the Tampines heartlands, a huddle of flats hum in the wake of harried working professionals chasing time. Their dishes have been scoured; mewling toddlers hustled off to their respective day-care centres as they kick-start their quotidian routines.

As construction saws and drills rasp to life in a nearby apartment in flux, grizzled seniors mill into a fluorescent-lit space beneath one of the blocks. There’s limited seating here, and the plastic chairs arrayed in an arc fill up quickly.

The Active Ageing Centre, run by charity Lions Befrienders, enables healthy ageing within the community for seniors across a wide socio-economic spectrum. Instead of listlessly shambling around void decks or deteriorating before television screens, they mark their days with Zumba classes, drum circle practice and other engaging pursuits. Here, the overriding mood is of quiet anticipation, not resignation.

In Singapore, where a projected one in four citizens will be aged 65 and older by 2030, wide-eyed predictions of a silver tsunami invoke consternation. But for all the attendant statistics cautioning of chronic conditions and healthcare challenges, growing old — as the centre’s beneficiaries evince — isn’t a wasting sorrow.

We asked three of them to recount the places that have left an indelible imprint in their lives. These memories burn bright, and in the words of Dylan Thomas, rage, rage against the dying of the light.

Street of the hidden cards

In the 1950s, we lived in a two-storey shophouse with a steep staircase at Joo Chiat Terrace. Our row housed about 10 units, including a provision shop, coffeeshops and Kim Choo Kueh Chang, which you can still find today.

A common sight there was the carrot cake street hawker who would mill rice into flour and push his cart out to the junction of Joo Chiat Terrace and Joo Chiat Place to sell his wares. Back then, the area was rather old and shabby, and crawling with mice and cockroaches. I can imagine how that would be scary for people who aren’t used to such conditions, but the coffeeshops and street hawkers would nonetheless draw crowds as there weren’t many other places to eat.

I particularly enjoyed the starfruit juice sold in the evenings, despite the drink being fermented in unsanitary conditions — inside open-air bathrooms, to be precise. Yes, we could actually look at the sky while washing up in a three-by-three metre space.

Illustration: Ken Lee.

Notably, our landlord operated an illegal gambling den hidden behind the provision shop in the afternoons, where elderly folk would gather around games of si se pai (four colour cards). I never got involved because I obviously don’t like gambling, but over time, I learnt to play the game just through observation. It was pretty interesting.

The rear of the shophouse was banked by a sandy patch home to a small Malay kampung with exceptionally friendly neighbours. Their attap homes were built on three-foot-high stilts, as the area was prone to flooding. Beyond the enclave was a copse of fruit trees including rambutan and guava trees. As kids, we’d routinely injure ourselves climbing these trees. Other antics include launching buah cheri (Malayan cherry) fruit at one another using slingshots.

One of my fondest childhood memories is of running in and out of the many doors to access our house. There must have been five or six entrances and now that I think of it, they may have been built to ensure an easy escape for the punters!

Koh Kia Guan (Andrew), 73

Market days

Ask anyone from my generation if they remember ti pa sat (directly translated to iron market in Malay and Hokkien), and they will recall an expansive iron structure at Beach Road that drew shoppers from across Singapore. Also known as Clyde Market Terrace, it stood where I.M. Pei’s angular Gateway towers now rise.

Having grown up in the area in the 1950s, I’m extremely familiar with the market, which is where we used to purchase all our groceries. You could find anything you wanted there, as it was a lot bigger than the markets you see today. Vegetables were spread out on trays placed on the ground, and live chicken and ducks could be chosen from netted cages.

As the precinct’s residents were predominantly Chinese, the market would be charged with a lively atmosphere during traditional Chinese festivals such as the Hungry Ghost Festival. During this period, two separate stages would be set up at the runnelled dirt compound behind the market, where lorries unloaded their goods. People would flock to the market to enjoy wayang (Chinese opera) and getai (song stage) performances here.

Illustration: Ken Lee.

Next to the market was the Beach Road Police Station, where we’d call out ‘mata’ (police in Malay), to the policemen in shorts. And further down the road stood The Alhambra, a popular cinema that was plastered with huge movie posters. Tickets were priced very cheaply back then, from 30 to 50 cents each.

My family and I lived at Arab Street close to the famous Sultan Mosque, which was located between two rows of shophouses. Some were purely residential while others functioned as provision shops. At the end of each day, we’d watch shopkeepers pack up their goods and bring them to the upper floors. I moved out from the shophouse into a one-room flat at Beach Road when I was 20, but still look back fondly at the sheer convenience that my former home brought.

Peggy Tan, 74

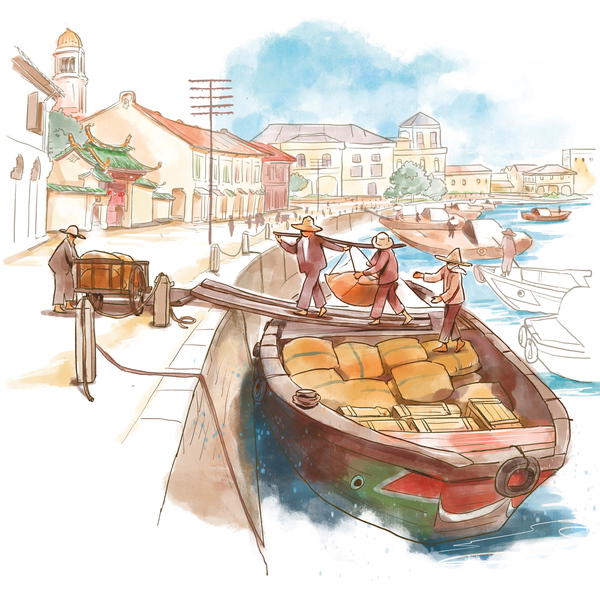

River of dreams

It was 1965, the year of Singapore’s independence. My father would cycle me along the two-way Havelock Road that runs along the Singapore River. I can vividly recall the foul stench emanating from the river, which you could smell from afar.

This was before the advent of air-conditioned transport, so you would have definitely be hit by the odour, whether you were travelling by trishaw, Hock Lee bus or private taxi. The water was floating with debris and so brackish that its depth could not be gauged.

As a secondary school student, I asked my teacher why the Singapore River was so dirty. She explained that due to the lack of proper sewage systems, people living in kampungs settled along the riverbanks would dispose of their refuse directly into the river. Even waste from street hawkers and pig farms was routinely dumped into the river. I remember then, questioning why Singapore did not want to improve its environment.

Littering the river were tongkangs (junk boats), from which coolies carefully balanced on wooden planks would unload goods to the warehouses lining the shore. It was really a sad view for us, watching them toil under the sun carrying heavy gunnysacks.

Further down from the river, street hawkers would station pushcarts at spots implicitly reserved for them. No one really lingered around the river though, due to the unsavoury conditions.

Then in the 1970s, former prime minister Lee Kuan Yew called for the clean up of Singapore River, and we could gradually see improvement in the area.

Presently, the water is green and much cleaner, just like a freshwater river should be. There is no more pervasive stench, and boat tours ply the body of water towards Marina Bay. On the other side of the estuary, you’re greeted by the iconic Merlion.

I’m highlighting the Singapore River as a reflection of the country’s remarkable transformation. We’ve come a long way from those polluted days, and I can proudly say that we’re a great nation.

Henry Lim, 68

Producer: Cara Yap

Videographer: Marcus Lin

Illustrator: Ken Lee

Hair & Makeup: Vivien Ng, using Nars, Chanel, Hourglass, GHD, and Chahong