Spiralling in what he considers a ‘perfect storm’ whipped up by a divorce and uneasy relationship with his boss, advertising professional Kenneth Chan sought therapy through Safe Space, an online platform connecting users to qualified mental health professionals.

The consequent video and in-person counselling sessions, covered by his company’s health benefits programme, yielded unbiased perspectives on handling his emotions.

“I had an anger problem and my therapist prescribed medication that helped calm me down enough to be able to listen and apply her inputs. I found this to be quite helpful, as opposed to ruminating over things I couldn’t control,” he shares.

Chan is among a growing grumble of Singaporeans who’ve turned to digital platforms over a pandemic that in many ways, eroded stigmas surrounding mental illness.

“More people are open to the idea of getting help online as it saves time and costs from travelling to counselling centres,” comments Porsche Poh, executive director of Silver Ribbon (Singapore). The mental health charity opened its web-based emergency chatline over one dreary pandemic lockdown.

If the past three years have catalysed help-seeking behaviour — The Samaritans of Singapore reported an 18 per cent year-on-year increase in calls for help in 2020 — this is mirrored in the uptick of local mental wellness start-ups that have hit their stride.

Just this June, digital mental health firm Intellect swept up an additional US$10 million for their Series A round that’s amassed a cool US$20 million. And Safe Space was seeded with US$250,000 garnered through a crowdfunding platform in 2020.

Removing barriers

These largely virtual counselling services satisfy a deep cultural antipathy to face-to-face therapy in an Asian country known for its reticence. “Singapore is a unique place where a lot of people are struggling not necessarily in the clinically severe distress range, but they may be moderate or higher-risk individuals leading fast-paced lifestyles. At the same time, we have been historically conditioned to sweep things under a rug,” says Theodoric Chew, Intellect’s founder in reference to landscape surveys conducted by the company’s inhouse research team.

The 26-year-old, who barrelled into the start-up scrum after completing his O’ Levels, surreptitiously buckled under anxiety as a teen for fear of being judged. His app combines free self-guided exercises centred on cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) with a telehealth segment for paying subscribers seeking life coaches and mental health professionals.

Wielding a similar B2B playbook is Safe Space, which boasts well-oiled and -coffered multi-national corporate clients including Procter & Gamble and Airbnb, as well as the Institute of Mental Health.

Its CEO and founder Antoinette Patterson underwent therapy after suffering from job burnout while working in advertising. “Counselling is very expensive and can cost upwards of $250 per session. If you need at least eight sessions that’s a good half of your monthly salary gone,” she shares, explaining that her company set out to unearth more affordable therapy options.

And they’ve managed to do so, primarily by roping in overseas therapists. “For experienced therapists, online counselling rates can start at $80 per session. Due to currency differences, our rates can be lower, at around $40 to $50 per session,” explains Patterson.

The platform issues voucher packages that can be utilised by employees and their dependents. According to Patterson, support structures are key to the effectiveness of platforms such as hers.

“The resources are there but if no one openly talks about it (mental health issues) and creates a safe environment for people to be vulnerable, they might not come forward and say hey, I need help.” Prior to undergoing therapy, Patterson herself confided in a manager at work, who helped in navigating her personal crisis.

Beyond the conventional therapy route, start-ups are giving individuals greater autonomy over their mental well-being in innovative ways enabled by emerging technologies.

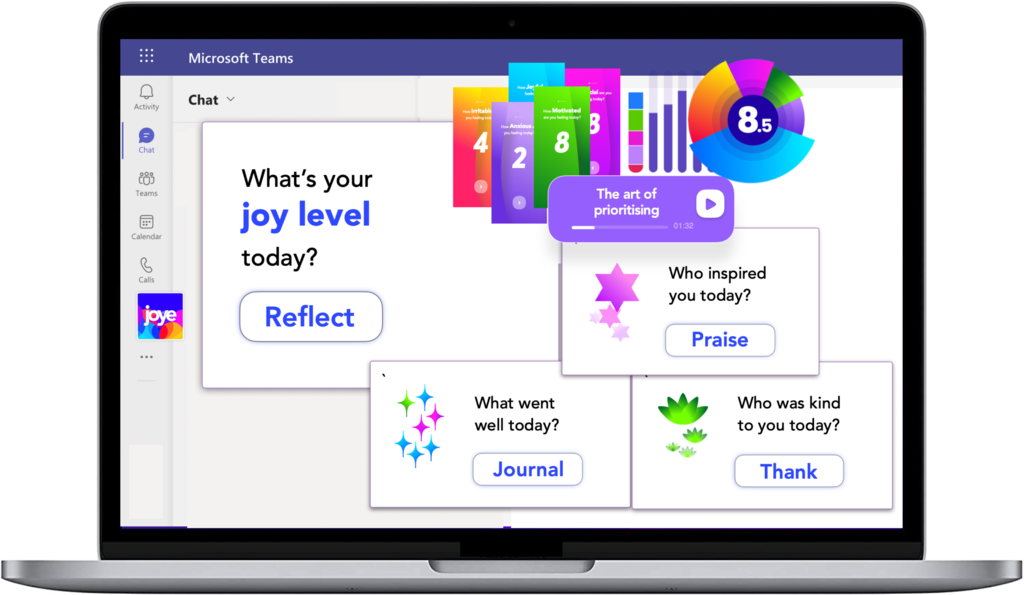

Joye, a recently launched AI-powered software that can be embedded in Microsoft Teams, analyses users’ diurnal patterns and prompts them to reflect on their state of mind through the chat function. Based on their responses to snappy multiple choice-style questions, it then suggests techniques and activities informed by a framework of CBT and positive psychology, including meditation and breathing exercises.

Its founder Sanjeev Magotra, a former suit who’s made the rounds of IT juggernauts such as IBM, Intel Corporation and Accenture, wants to empower digital natives to track their ‘mental fitness’— much like how a Fitbit is compulsively intertwined with physical routines.

“In order to help the 85 per cent or so of the population that isn’t clinically diagnosed with a mental illness to take care of themselves the right way, we need to have well-timed intervention. The solution must be woven into our lifestyle and easy and intuitive to use, much like how you measure your 10,000 steps in physical fitness,” says the CEO, who witnessed the launch of pioneering AI computer dialogue system IBM Watson.

He is, however, quick to distinguish Joye from other predictive AI tools that may decipher users’ emotional state based on facial or voice recognition features. “Most times these kinds of technology give you a superficial first layer of emotions, which tend to be multi-faceted and can only be distilled through reflection.”

No silver bullet

Digital start-ups such as Safe Space, Joye and Intellect have enhanced accessibility to mental wellness services for working professionals.

However, there are clear limitations, such as the lack of continuity in usage. Chan, for instance, shares that he’s put his Safe Space therapy on the backburner since his company pared down its mental health coverage.

Chew says that promoting mental well-being in the workplace warrants a top-down approach. “If it is purely a HR-driven effort without the full buy-in of management it is always going to be half-hearted. This trickles down to policies such as flexible working arrangements or allocating certain days in a month off.”

There’s also a question mark over efficacy: Due to their nascence, most digital mental wellness platforms have yet to be externally validated through rigorous clinical research.

Perhaps the most glaring risk surrounding the use of such platforms, run by for-profit companies, relates to users’ data being inappropriately monetised. That’s a hornet’s nest that Joye, whose software is hosted by a Big Tech-run platform, wants to avoid at all costs.

Sanjeev claims that their encrypted data is out of bounds to Microsoft, and while corporate clients can access a view of their companies’ overall emotional health in the form of a simple bar chart, individual data is safeguarded by Joye. The company initially dabbled in hitching facial recognition features onto their product, but they were ultimately scuttled due to privacy infringement concerns.

All three firms I spoke to cite stringent data encryption practices. For those still sitting on the privacy fence, Patterson offers this advice: “Always look at companies’ privacy policies, which should list how they are utilising your data, how often they delete it and the scenarios under which they will break confidentiality — which is a very common practice if you present a high risk of suicide or self-harm.”

What pundits can probably say with certainty, is that with mental well-being no longer a rarefied topic in Singapore, digital health adoption has yet to hit its high-water mark.

Chew shares that the next frontier of such services may address the specialised needs of specific demographics such as women and youth.

“My view is that in three to five years’ time, many of us would have seen a therapist at least once, especially in certain demographics that are more open to it.”