Some jewellers design, craft, and embellish. Then there is Cartier, a maison that accomplishes all these things and is not afraid to go even further to pursue excellence. A place of innovation and artistic expression, audacity has defined its identity since its founding.

In the world of Cartier, adornment is more than simply an exercise in beauty; it evokes wonder. Its legacy is to astonish, innovate, and explore uncharted territory boldly—and that spirit is on full display at “Cartier, the Power of Magic”, a new exhibition at Shanghai Museum East.

Until 17 February, it combines the brand’s storied heritage with cutting-edge AI to explore the dynamic interplay between tradition and technology, craftsmanship and creativity.

At its heart are more than 300 exquisite pieces, primarily from the Cartier Collection, an archive spanning the 1850s to the early 2000s. A testimony to its foresight, it began acquiring its early creations—jewellery, timepieces, and other pieces de resistance—for preservation from the 1970s.

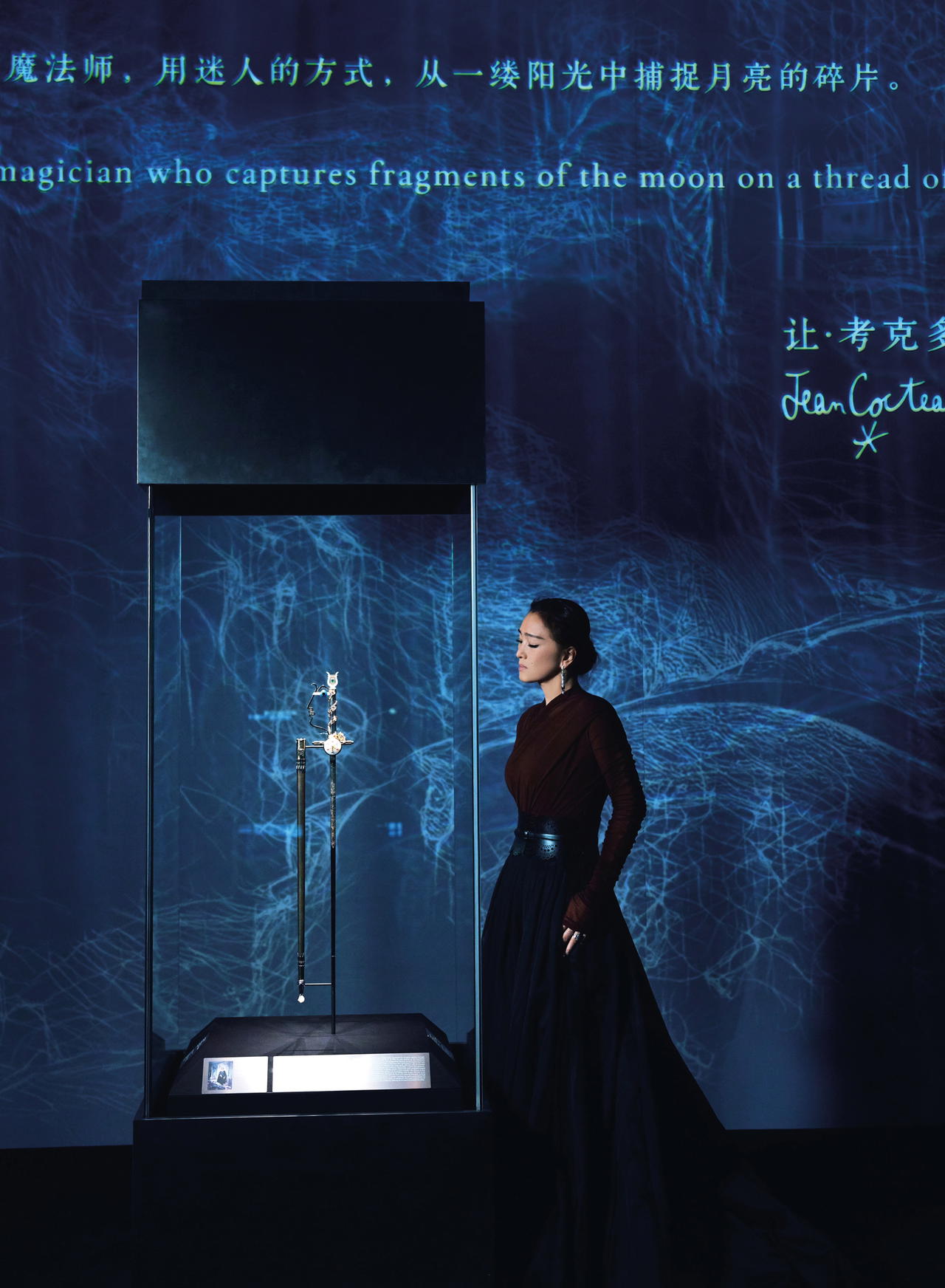

By 1983, this endeavour crystallised into the Cartier Collection, which now encompasses approximately 3,500 meticulously conserved works. A highlight of the exhibition is the Cartier sword for Jean Cocteau, created in 1955 for the French writer, artist, and filmmaker inducted into the Académie Française.

As a symbol of its magical artistry, the precious ceremonial blade boasts gold, diamonds, an emerald weighing 2.84 cts, and rubies donated by Gabrielle Chanel and French socialite Francine Weisweiller.

Among the other treasures are tiaras, including several commissioned by royal families, that prove Cartier’s reputation as the jeweller of kings and king of jewellers. In combining tradition and innovation, and elevating ceremonial adornment into an art form, they became the precursors of other iconic creations that have graced influential figures throughout history.

One such creation is the Tutti Frutti necklace, famously owned by Daisy Fellowes, the stylish Singer sewing machine heiress. This vibrant masterpiece, with its colourful medley of carved emeralds, rubies, and sapphires, represents Cartier’s pioneering embrace of Indian artistry in the early 20th century.

Similarly, the crocodile and snake necklaces—jewellery as daring as their original owner, Mexican actress María Félix— draw the eye. Featuring two fully articulated reptiles set with 1,023 yellow diamonds and 1,060 circular-cut emeralds, the crocodile necklace was modelled after Félix’s pet baby crocodiles.

Additionally, the exhibition features jewellery steeped in Hollywood glamour, including the Hutton-Mdivani Jadeite Necklace, once owned by heiress Barbara Hutton, whose jewellery collection was legendary. When it went up for auction in 2014, it was sold to Cartier for more than US$27.4 million (S$37.1 million), cementing its status as one of the most expensive jadeite pieces ever sold at auction. The jewellery of Princess Grace of Monaco also exemplifies Cartier’s long-standing connection with royalty and cinema.

These jewels are presented alongside artefacts from museums worldwide, ranging from porcelain dishes and bronze busts to jade table screens and coral dragon figurines. Each has been carefully selected to explore the exhibition’s central theme: the transformative power of magic.

This magic, as Cartier defines it, lies in the profound allure of gemstones and the ingenuity of the artisans who transformed them into objects of beauty, meaning, and status. Through this dialogue between historic artefacts and its creations, the exhibition reveals how craftsmanship and imagination have the power to turn mere objects into symbols of wonder and desire.

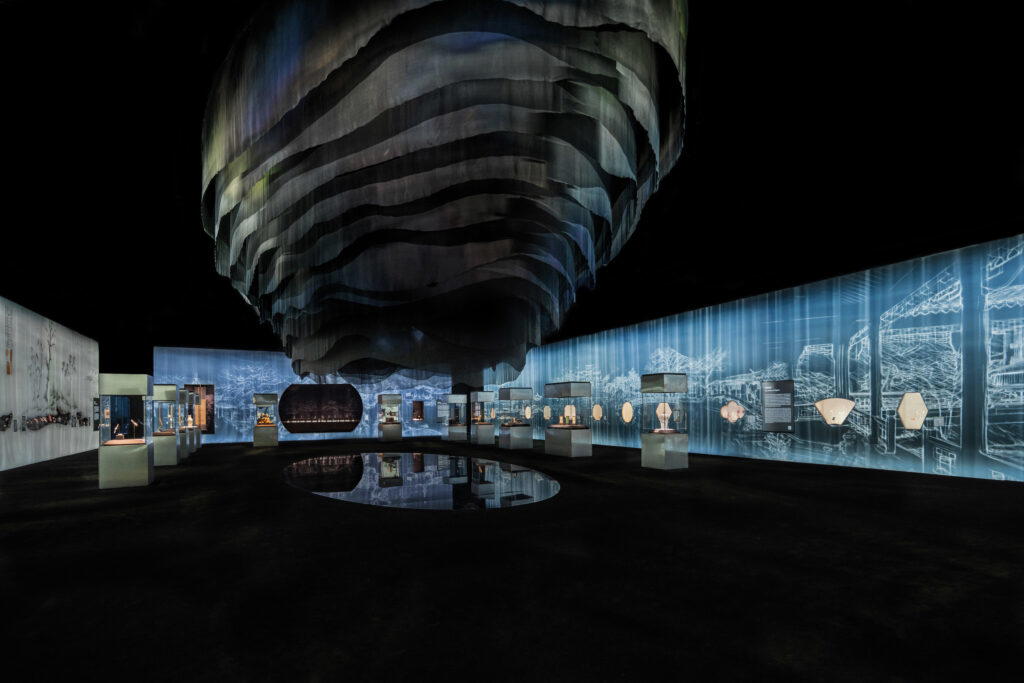

The visionary scenography and visual direction of Chinese artist Cai Guo-Qiang enriches this narrative. An AI model Cai and his team developed, cAI, plays a central role. Far from an analytical tool, it functions as a collaborator, engaging in what Cai describes as “metaphysical discussions about the universe, the spirituality of the unseen world, and an alchemist-like artistic methodology”.

Recognising the importance of practical training for his AI model, he proposed that cAI—which he calls his doppelganger—serve as the exhibition’s artistic director.

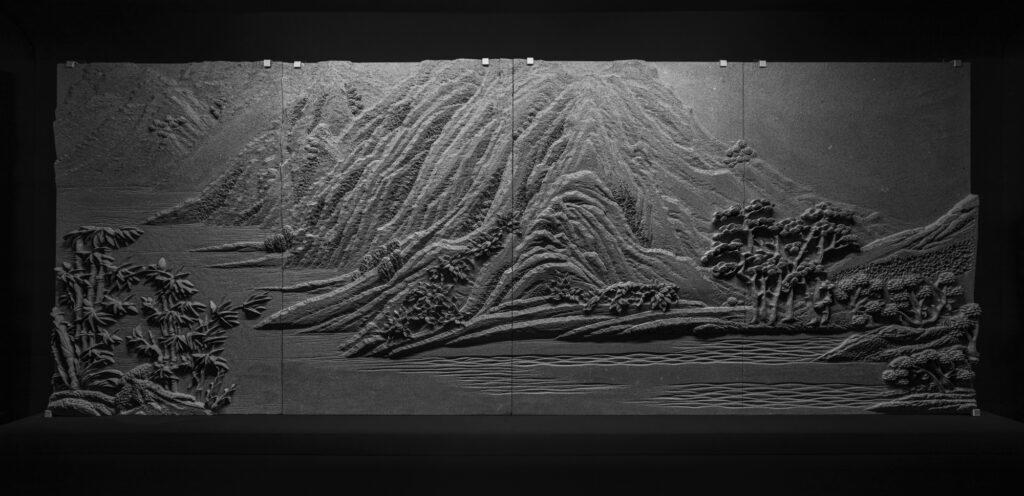

Inspired by Ni Zan-style landscape drawings and Chinese courtyard manuscripts, the 3D-printed and AI-generated backdrops are crafted in carved ceramic and stone by artisans from Quanzhou, Cai’s hometown. As these elements illustrate the rich history of Chinese culture, they also reflect Cartier’s commitment to combining historical depth with contemporary creativity.

The exhibition concludes with a lingering question: what makes something magical? Is it the preciousness of gemstones, the innovation of artisans, or the stories layered within each creation?

“Cartier, the Power of Magic” doesn’t claim to answer this outright. Instead, it invites visitors to wander through a kaleidoscope of history and modernity, where tiaras and crocodiles shimmer under museum lights against an evocative AI-generated backdrop as eye-catching as the exhibits.