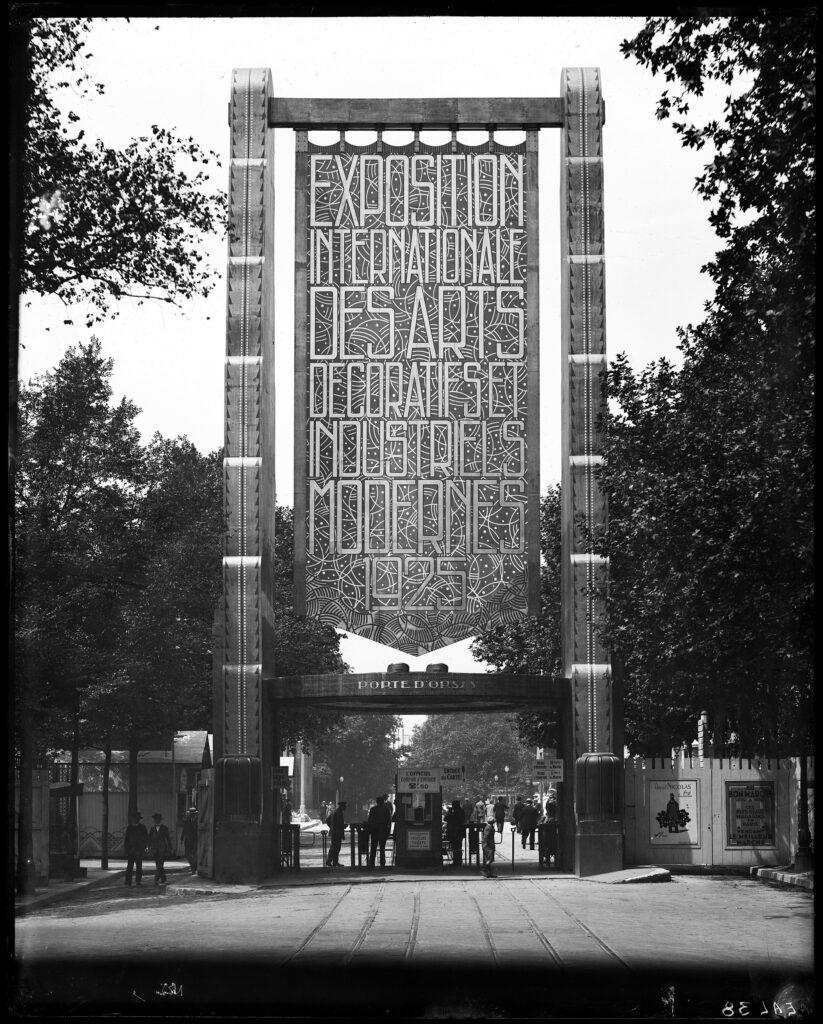

Only a century ago, the “International Exhibition of Modern Decorative and Industrial Arts” turned Paris into a showcase for modern beauty. The Jazz Age was in full swing in 1925 when visitors poured into France’s capital—spanning the esplanade of the Invalides and the entrances to the Grand Palais and Petit Palais—to witness how design honoured its history while looking towards the future.

This same optimism now fills the Musée des Arts Décoratifs (MAD)’s “1925-2025: One Hundred Years of Art Deco” until 26 April 2026. The expansive exhibition, featuring 1,000 pieces curated by Bénédicte Gady, director of the museum, and Anne Monier Vanryb, curator of its modern and contemporary department, celebrates the birth, brilliance, and enduring appeal of the movement.

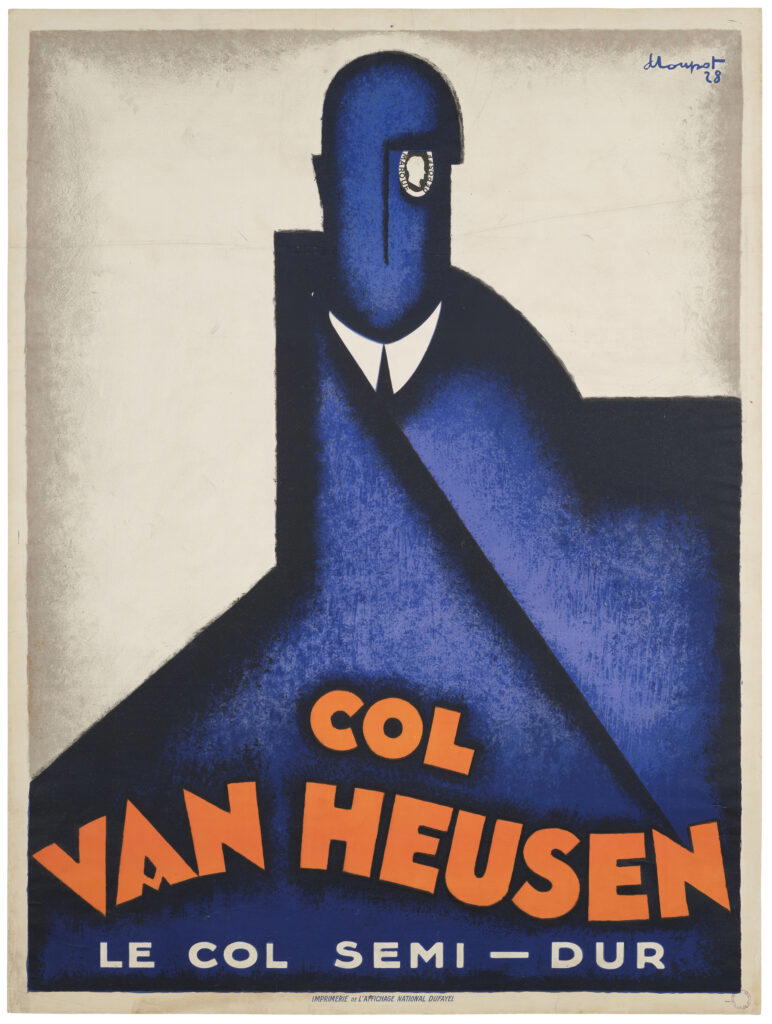

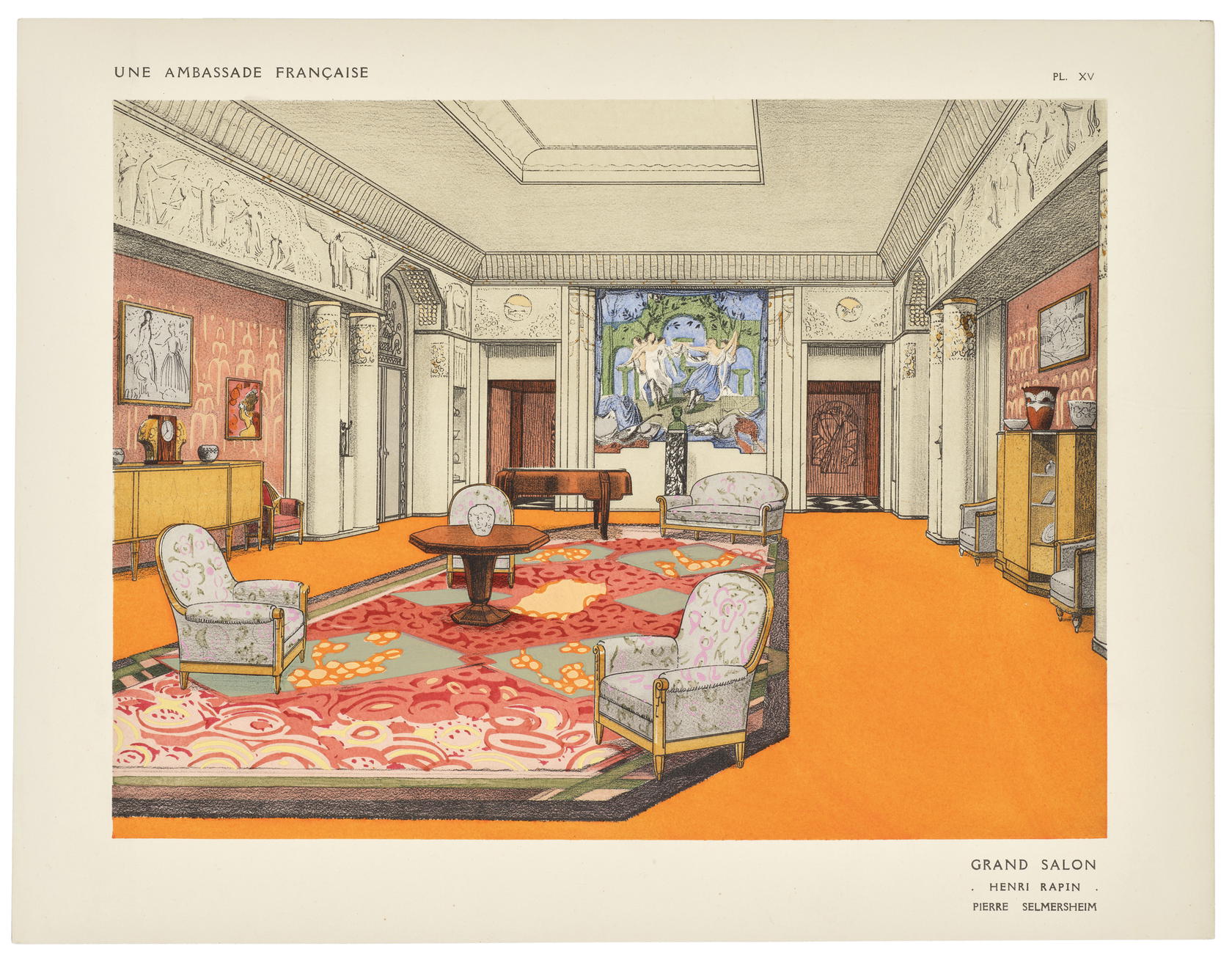

Sculptural furniture, stained glass, wallpaper, silverware, exquisite jewellery, ceramics, objets d’art, posters, textiles, and fashion depict the geometry, sensuality, and craftsmanship that defined the style.

They also reveal how it still animates luxury design today. “Contrary to popular belief, Art Deco is not a sudden break from Art Nouveau,” states Lisa Jousset-Avi, assistant curator of the museum’s modern and contemporary collections. “It’s an aesthetic reflection that began in the 1910s with increasingly synthesised decorations, a rationalisation

of object forms, and a growing interest in clean lines.”

Its appeal sits in productive contrasts: modern yet opulent, disciplined yet decorative. “It brings together a variety of aesthetics and sources of inspiration,” Jousset-Avi adds.“It draws on the past, from Roman antiquity to the Louis-Philippe style, as well as other cultures, from the Orient to the Far East.”

That cosmopolitan curiosity yielded a lexicon of fountain sprays, stylised florals, sleek gazelles, and radiant sunbursts—motifs that still echo across runways and hotel lobbies. The Abstract, Cubist, and Fauvist movements sharpened the geometry and colour, visible in works such as Sonia Delaunay’s textiles.

BOLD Luxury, romance & innovation

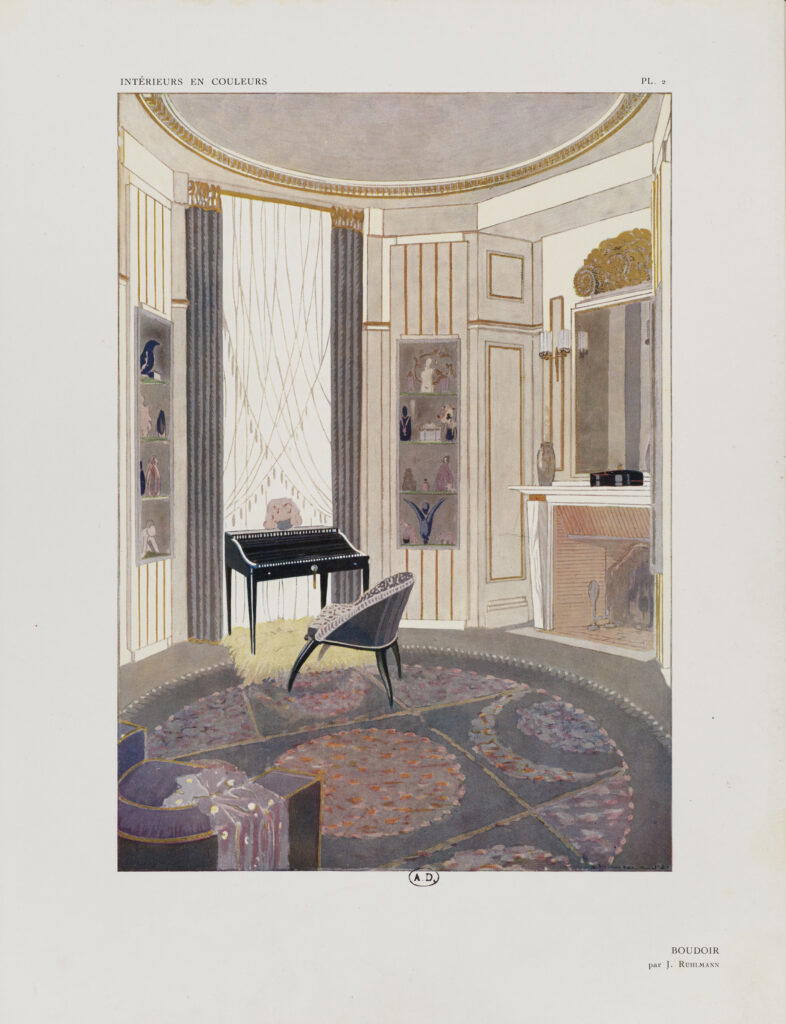

Materials were luxurious and intended largely for the wealthy. Designers like Jacques-Émile Ruhlmann combined amboyna wood and ivory; Jean Dunand turned lacquer into sculpture; Clément Mère worked with embossed leather and shagreen; and Puiforcat sublimated jade. “It’s an art of materials,” Jousset-Avi explains, “a veritable science of combining precious materials or innovations with techniques that are often sufficient for ornamentation.”

The 1925 exposition marked France’s return to the world stage after the war and set the tone. “It was a major event that had a huge impact,” says Jousset-Avi. “France was then a victorious country, a vast colonial empire showcased in its own pavilion, supplying objects, furniture and imagery on display with precious and exotic materials.”

Those pavilions are gone, but their spirit survives in the MAD’s collection as well as the exhibition’s immersive scenography by Atelier Jodar and Studio MDA.

Three designers anchor the show—Ruhlmann, Eileen Gray and Jean-Michel Frank—each given a dedicated room to underscore the range of aesthetics. Ruhlmann mastered line and contrast; Gray excelled in cabinetmaking and lacquer; Frank reduced ornament to essentials, working in parchment, straw marquetry and mica.

“Their approaches embody the movement’s effervescence,” Jousset-Avi says, “and still influence contemporary studios such as Atelier Jallu.”

Visitors will see André Groult’s anthropomorphic chiffonier, Pierre Chareau’s ambassador’s desk, Gray’s lacquered Sirène chair and Jeanne Lanvin’s iridescent cheik cape.

They will also encounter more than 80 Cartier works—some never previously shown—ranging from tiaras and watches to cases, drawings, archive papers and the Bérénice necklace. “We’re showing recognised masterpieces alongside lesser-known objects that are just as compelling,” Jousset-Avi adds, citing Eugénie O’Kin’s ivory vase and Madeleine Pangon’s vivid batik.

Few institutions are as entwined with Art Deco’s story as MAD, having hosted the movement’s salons from the very beginning. Jousset-Avi discloses, “The Union Centrale des Arts Décoratifs was initially involved in Art Deco in its contemporary form, participating in trade fairs and exhibitions to promote the decorative arts through the museum’s showcase.” Those early acquisitions now anchor one of the world’s richest collections.

past as prologue

The museum also helped spark the style’s return. “Les Années 25”, the 1966 exhibition curated by Yvonne Brunhammer, reignited global fascination with the style. That revival continued through the 1970s, driven by French interior designer and collector Jacques Grange’s interpretations for prestigious clients such as Yves Saint Laurent and Pierre Bergé.

In this show, Grange has been given carte blanche to create a contemporary dialogue. Its theme of chairs and desks is a testament to the continuity of the line from 1925 to 2025.

If Art Deco had a signature fantasy, it was travel—streamlined, romantic, and impossibly chic, as epitomised by The Orient Express. Decorated by René Prou and René and Suzanne Lalique, the train carried salon aesthetics onto the rails with marquetry, etched glass and silk-lined comfort.

“In the collective imagination, the period lives through symbols,” says Jousset-Avi. “We wanted to evoke Art Deco through one of the symbols of 1920s modernity: cross-border transport, which has fuelled imaginations since Agatha Christie’s Murder on the

Orient Express.

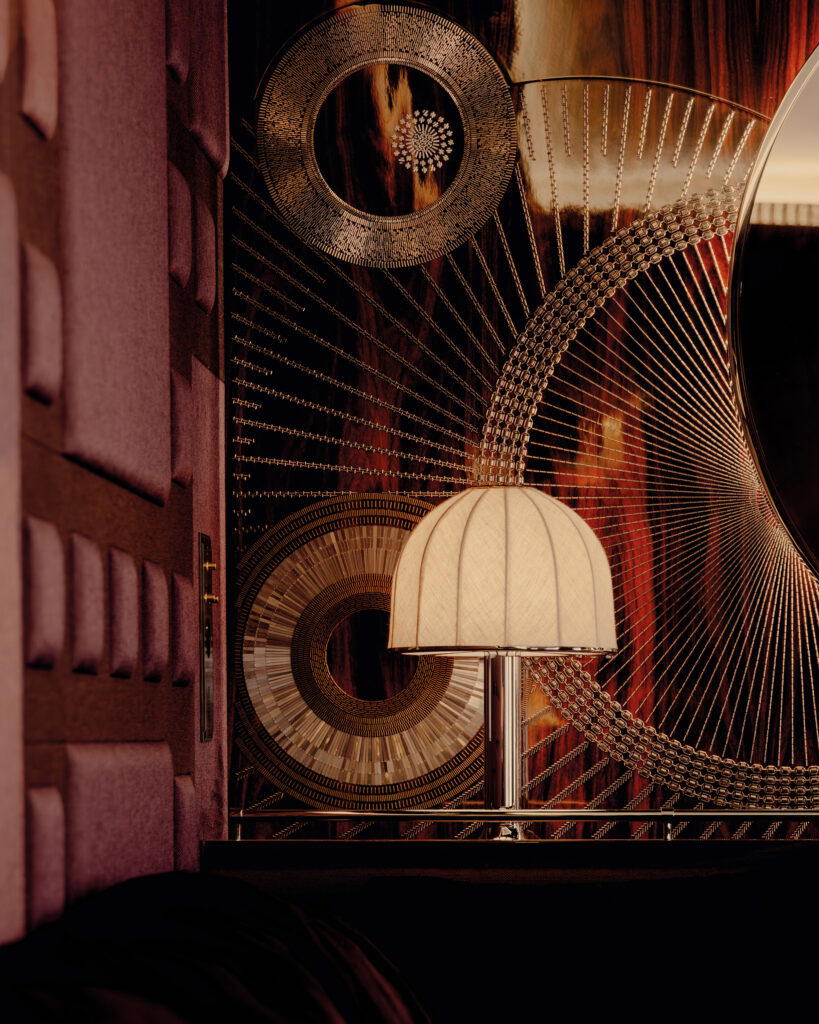

“We also wanted to connect it to the contemporary world, thanks to Maxime d’Angeac’s new Orient Express.” Occupying the MAD’s vast nave, the installation sets a 1926 carriage cabin from the collection beside three full-scale interior models of the future train, conceived by d’Angeac, Artistic Director of the brand’s rebirth.

Working with embroiderers, sculptors, watchmakers, coppersmiths, glassmakers, cabinetmakers, lighting designers and engineers, he shows how the language can be reinterpreted today. Handcrafted wood and glass meet high-tech precision to deliver what the exhibition calls “forward-looking luxury”.

Art Deco’s reach was never confined to France. “The resounding success of the 1925 exhibition was an early catalyst for its global spread,” says Jousset-Avi. American architects drew its vertical thrust into Manhattan’s skyline; Japan commissioned French masters like Henri Rapin; and the great ocean liners Normandie and Île de France became the new ambassadors of French art de vivre.

“Each nation embodied Art Deco principles, drawing on its own cultural history, as in Brazil and Sweden,” she adds.

Design dialogue

One of the movement’s lasting legacies is its interdisciplinary spirit—the seamless integration of art, craft and industry across design, architecture, fashion and the decorative arts.

“This idea is at the heart of the period,” says Lisa Jousset-Avi. “Through the energy of multi-talented creators and the collaboration between designers, craftsmen and manufacturers, interiors were conceived as a complete art form.”

Why does it still captivate a century on? Jousset-Avi notes that contemporary designers continue to mine its imagery—sometimes overtly, evoking luxury and the Roaring ’20s; sometimes more quietly, through straw marquetry, dark woods and enveloping ensembles. The codes remain clear and durable: clean lines, contrast, colour and craft.

That persistence points to a wider truth about design: the dialogue between heritage and innovation never stops. As the 1925 exposition fused age-old techniques with modern industry, today’s makers pair artisanal skill with digital fabrication and more sustainable practice.

Art Deco’s lesson is less about nostalgia than optimism: the belief that beauty and progress can co-exist. From Jean Dunand’s lacquered screens to Lanvin’s glistening gowns, and the reimagined Orient Express, “1925-2025: One Hundred Years of Art Deco” advances a simple argument: elegance grounded in craft and invention endures.