At London’s Victoria and Albert Museum, “Cartier” (through 16 November 2025) opens in a hushed gallery with a show-stopper: a 1903 tiara made for Consuelo Montagu, Dowager Duchess of Manchester. In elegant garland style, its French neoclassical lines unfurl in sweeping, heart-shaped arcades, each alive with light. More than a thousand brilliant-cut diamonds—stones owned by the duchess—glitter across the diadem, an early statement of Cartier’s precision, restraint and theatrical flair.

A pivotal moment in Cartier’s evolution as a luxury maison, the ‘Manchester Tiara’ was more than that. Designed by Cartier in Paris for the American heiress who married into the British aristocracy, it embodied a cross-cultural identity that helped define the company’s future in Paris and beyond it.

By the early 20th century, founder Louis-François Cartier’s grandsons built the brand into a global empire: Louis in Paris, Jacques in London, and Pierre in New York.

never imitating, always evolving

As the UK’s first major retrospective in almost 30 years, “Cartier” features over 350 objects, including royal tiaras, maharaja commissions, and iconic brooches. According to Pierre Rainero, Cartier’s Director of Image, Style, and Heritage, this is not a vanity project. Independently curated, the exhibition explores culture and craft.

“Our role is to open doors for curators. Cartier exhibitions are not curated by us. We want an external and scientific vision of our work. We are only responsible for fact-checking and authentication,” he says.

Such openness in allowing its legacy to be viewed through an objective lens underscores Cartier’s quiet confidence in its history. The exhibition’s first section explores its creative DNA and highlights how its visual language developed over time.

In terms of aesthetics, Cartier is known for fusing traditions. Early in the 20th century, for example, it incorporated 18th-century French motifs along with Islamic art, Indian jewellery, and Egyptian symbolism. These syncretic design elements are evident in pieces such as the ‘Scarab Brooch’ (1925), featuring colourful, calibre-cut gem-set wings. The diamond-set, openwork piece is inspired by the bazuband, a traditional upper-arm bracelet from India.

Such influences have always been about transformation, not imitation. “Our founders looked at Cartier as continuously innovating,” says Rainero. “The very notion of beauty is constantly evolving, so you cannot be framed by what has already existed.”

Unleashing creativity In every creation

The next section of the exhibition demonstrates Cartier’s technical mastery, as well as its design brilliance. It explores the inner workings of its ateliers, from sourcing rare and unusual gemstones to pioneering in-house workshops.

Taking centre stage is the ‘Panther Bangle’ (1978) in platinum and pave diamonds, with emerald eyes and onyx spots. With its sculptural form, twin panther heads and hinged design, it paved the way for the Panthere de Cartier’s 1980s renaissance across bangles, watches, and high jewellery.

Also included is the Cartier ‘Hutton-Mdivani Necklace’ (1933), which American heiress Barbara Hutton received as a gift from her father Franklyn Laws Hutton on the day of her wedding to Prince Alexis Mdivani of Georgia in June that same year. The imperial green jadeite bead necklace was strung with 27 gigantic orbs and a clasp adorned with a navette-cut diamond. How these brilliant green beads of striking perfection were carved from the same boulder is still a mystery.

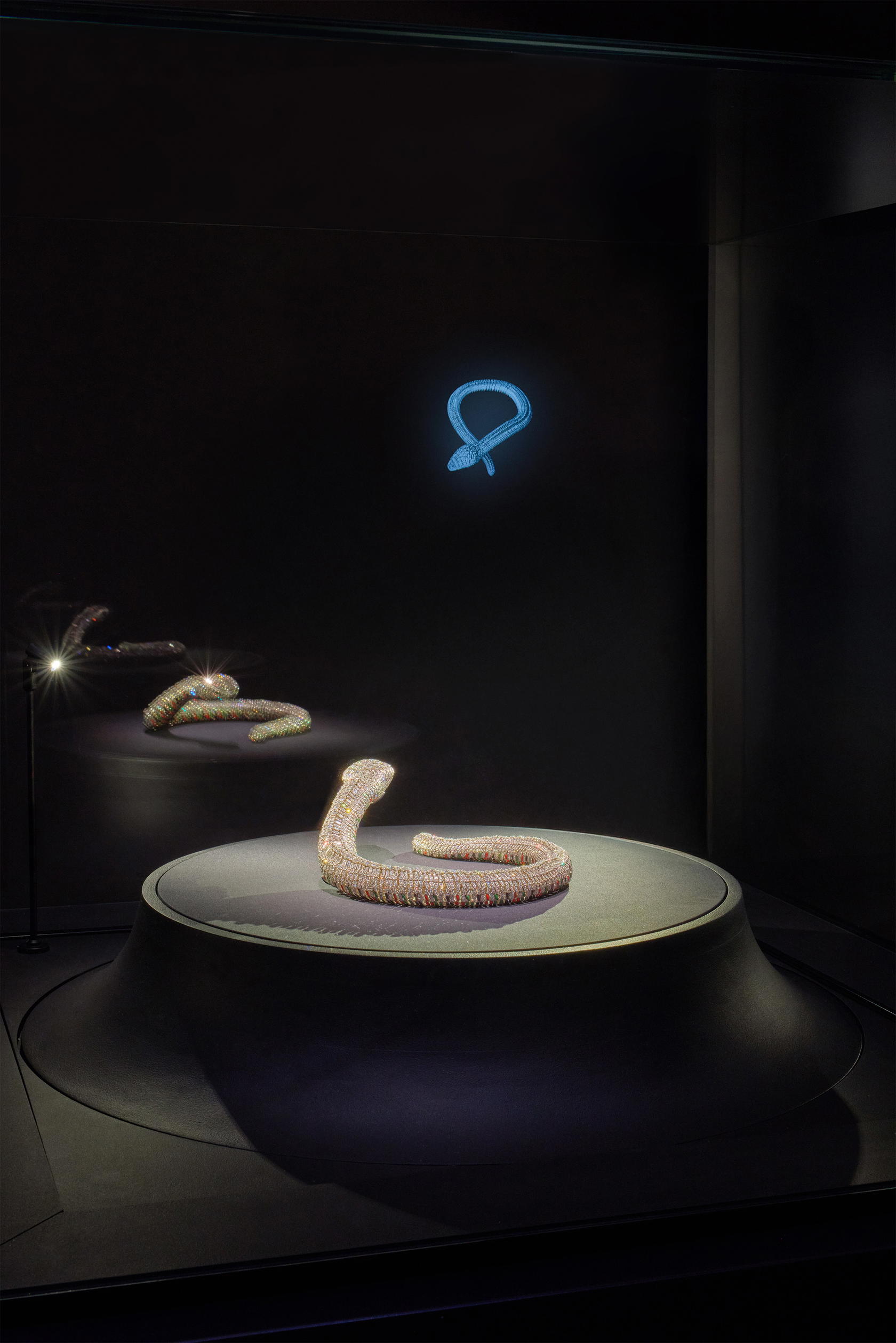

No less spellbinding is the ‘Snake Necklace’ (1968) commissioned by Mexican film icon María Félix. Cartier’s artisans created a life-size serpent in articulated platinum, adorning it with 2,473 diamonds and an underside of scales in black, red, and green enamel. The hues referenced the Mexican flag.

The maison is also known for its mastery of horology. Through its iconic timepieces, the exhibition traces technical milestones, including the ‘Santos’ (1904), the world’s first pilot wristwatch, ‘Crash’ (1967), purportedly derived from a car accident and later embraced by punk royalty, and ‘Carabiner’ (2024), with its watch face suspended on a metal clip.

Cartier’s legendary mystery clocks are even more mystifying. Introduced in 1912, they use transparent rock crystal to create the illusion of floating time without a handle. Resembling a torii (Japanese Shinto shrine gate), the ‘Large Portique Mystery Clock’ (1923) made of rock crystal, onyx, galalith (originally coral), diamonds, enamel, gold, and platinum stands out.

Cartier’s ethos is reflected in these objects, says Rainero. “It is intrinsically part of a jeweller’s job to evolve. When you understand the role the objects you create for your clients play, you evolve.”

Lastly, we look at Cartier’s role in fashion. Its expertise and fantastical narrative have transformed stars into icons over the decades. Among the highlights is an opal-and-diamond tiara from 1937, commissioned by the Dowager Duchess of Devonshire and later worn as a necklace at Queen Elizabeth II’s 1953 coronation.

There are two other iconic fashion moments that stand out as well. As Grace Kelly’s second engagement ring, Prince Rainier of Monaco gave her a 10.48-ct emerald-cut diamond set in platinum flanked by two baguette-cut diamonds in 1956, which she wore in her final movie High Society. Then there is the ‘Scroll Tiara’ (1902) Rihanna wore on the cover of the September 2016 issue of W magazine.

There is only one way to describe the “Cartier” exhibition: Exceptional.