Liu Bolin, also known as The Invisible Man, first “vanished” in 2005. It was during a

non-verbal protest against the demolition of the Beijing artists village where he worked in preparation for the 2008 Olympics.

Using only acrylic paint, he painstakingly incorporated himself into the ruins without any digital manipulation. Motionless for hours, with his eyes closed and barely visible, he photographed the moment.

The piece became the first in his renowned “Hiding in the City” series, which uses disappearance as an active expression of resistance rather than surrender. Relying on body art, optical illusion, living sculpture, and photography, he conveyed the frustration of urban anonymity in an era of rapid change in a striking manner.

According to Liu, China’s society faced various problems after the Beijing Olympics, including an economic crisis, food safety issues, environmental pollution, and demolition. “I began to use my work as a silent language to express what I saw in China and the world. I hope they can attract people’s attention and allow them to think deeply about different social issues. They are like a mirror, reflecting back on ourselves.”

The Power of Disappearing

Since that first performance, Liu has taken his disappearing act to new heights, blending into supermarket shelves, newsstands, theatres, drifting icebergs, walls of Communist Party propaganda, and portraits of Chairman Mao.

He has even painted himself against the Great Wall of China, the Colosseum in Rome, the Hollywood sign, the glass pyramid of the Louvre alongside French artist JR, and even Singapore’s Merlion set against a cityscape of towering skyscrapers.

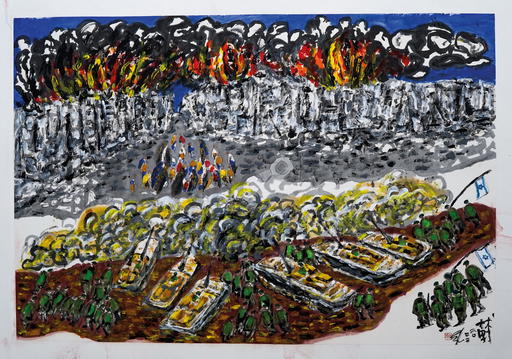

Delving into the art history canon, he has appropriated Leonardo da Vinci’s ‘Mona Lisa’ and Picasso’s ‘Guernica’, using human subjects as his canvas. “In my works, the background is very important,” he points out. “Choosing where to hide is to highlight the meaning hidden in that place.”

But Liu doesn’t stop at disappearing. His art is a vessel for more profound political and social commentary. From creating futuristic heads made of electronic circuits and copper wires concealing video cameras—where the art observes the viewer—to live-streaming Beijing’s smog via mobile phones strapped to his orange lifejacket, he turns the invisible forces shaping our world into tangible, provocative works. Whether he addresses pollution, financial power, or consumerism, his work consistently calls for reflection and action.

Art as a Calling

Born in 1973 in Binzhou, Shandong Province, Liu made his toys as a child. He later graduated from Shandong Arts Institute, before earning a master’s in sculpture from Beijing’s Central Academy of Fine Arts in 2001. “Under the guidance of my graduate advisor, Sui Jianguo, I gradually came to comprehend the importance of focusing on reality in art,” he says.

“Additionally, I recognised that art must not only inherit the evolution of artistic styles throughout history, but also address the challenges posed by contemporary realities. As a result of these insights, I shifted my observational perspective from formalism towards a greater emphasis on reality and began actively conveying my personal sentiments about society through my work.”

Today, Liu’s work merges science, technology, and art. His “Hacker” series incorporated mobile phone circuit boards and hacker networks to examine themes of the virtual world, mobile software, and cloud storage. It set the stage for the “Chaos” series, which uses outdated technology to create fragmented, incomplete forms through 3D scanning and printing.

He describes his hollow self-sculpture as offering a “4D perspective” that encourages both external and introspective examination. “I want my work to encourage thoughtful reflection on humanity, connecting the real and virtual, present and future, wholeness and fragmentation, certainty and uncertainty.”

Hiding in Singapore

Liu’s latest project, “Hiding in Singapore”, explores community and identity. In January, as part of Singapore’s 60th birthday celebrations, he unveiled ‘We Are the World’, a powerful photo performance featuring 60 participants of diverse races, nationalities and creeds. In this single artwork, he gathered his largest group of people ever to disappear into the steps of the National Gallery Singapore.

It conveyed a powerful message of love, unity, and peace, reminding us that mankind itself is the world. Although Singapore shares traits with global cities such as New York, Paris, Hong Kong, and London, it has fewer social tensions than Europe and the US,

Liu observes.

“I explored the possibility of harmonious coexistence among people from different religions and cultures through ‘We Are the World’. Singapore offers a model for the current political and military landscape and a vision for peaceful survival in the future.”

In a second performance at Clifford Pier, Liu collaborated with former harbour boatmen, blending them into the pier’s historic architecture. The piece reflected Singapore’s evolution from a colonial port shaped by migrants into a global metropolis, capturing a pivotal moment in its history.

It was their labour that bore witness to the nation’s development and to those who fought to build it, according to Liu. “Ordinary individuals may remain unseen, but their contributions sustain the country. By returning this group to their former workplace, I hoped to honour the spirits and strengths embedded in Singapore’s past—acknowledged not just in history but in the journey of art itself.”

Liu’s work, whether in the vineyards of Champagne or set against Singapore’s monuments, is a masterclass in making the invisible visible. His process, which can take hours and even days, is similar to a game of hide-and-seek. Viewers are left questioning their perception, believing there is no one there when, in fact, someone is hiding in

plain sight.

He explains that he decided to vanish into the world around him. ‘Some say I disappeared into the landscape; I say the environment took hold of me.”

Through his art, he compels us to see our surroundings, our societies, and ourselves with greater clarity. “My fundamental intention behind these works is to reflect upon the world’s imperfections, striving for transformation through art to contribute positively towards a better world.”