Annie Leibovitz has never been just a photographer. She has been a cultural narrator, focusing her lens on the people and places that define modernity for more than half a century. Rather than simply capturing, her images stage, probe, and mythologise.

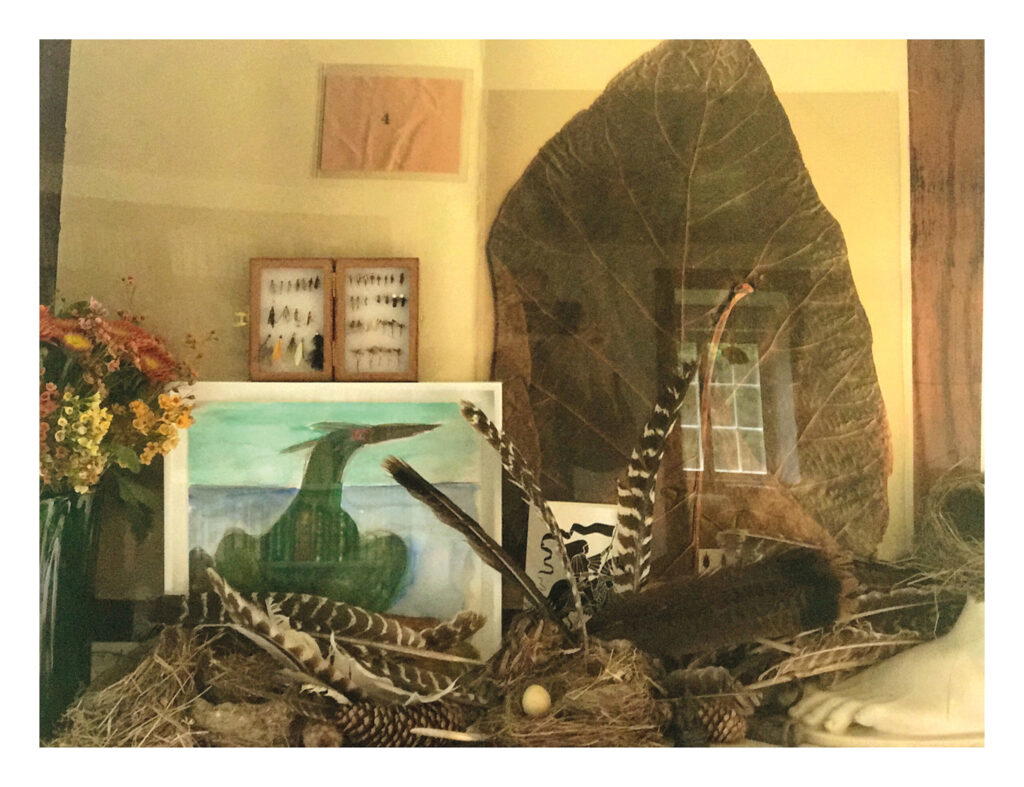

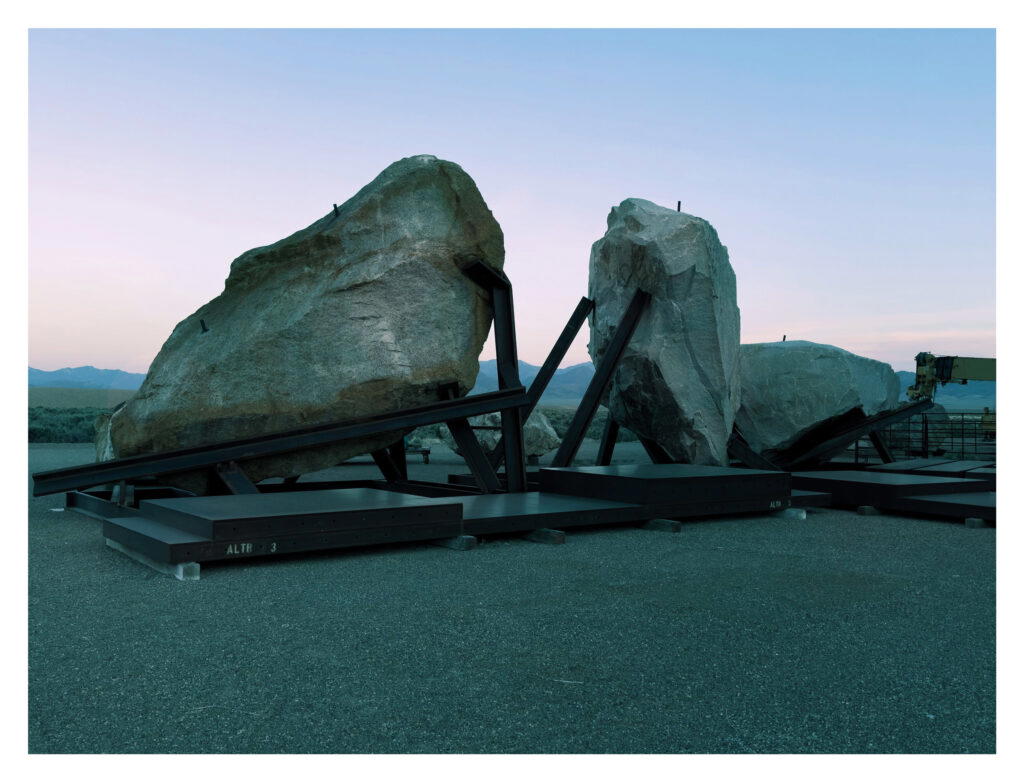

This summer, she took centre stage again with “Annie Leibovitz. Stream of Consciousness” at Hauser & Wirth Monaco from 2 July to 27 September. A far cry from traditional greatest-hits retrospectives, the exhibition presented two decades’ worth of landscapes, interiors, still lifes, and portraits, including those here, arranged in a rhythm that invited visitors into her intuitive world.

A portrait of a Supreme Court Justice seated beside a stark glacial landscape; a photo of a singer sprawled on a sofa facing a snapshot of a cluttered artist’s studio… “It was so interesting to think about the work out of order,” she says of abandoning her usual chronological approach. “It was definitely a stretch for me, but I really loved it. I’m very interested in process. I love process.”

Born in 1949 in Waterbury, Connecticut, Leibovitz grew up as one of six children in a family constantly on the move due to her father’s career in the United States Air Force. Both a disruption and a gift to her, she says, “It was a great childhood because you got to move every couple of years and reinvent yourself,” she recalls. The going in and out of so many different places was also a precursor to portraits.

A modern dance instructor, her mother infused their home with creativity, introducing the children to performance, music and formal family portraits, along with early experiments with 8mm film, which left Leibovitz fascinated by how images are interpreted and remembered. “She was a creative force, a hard act to follow,” she recalls.

She entered San Francisco Art Institute in 1967 as a painting student, but soon turned to photography after a camera purchased on a family trip to Japan unlocked a passion. “Photography was immediate and gave me confidence. I was awkward and gangly, and the camera just made me feel comfortable.” By 1970, she had switched majors and began shooting for Rolling Stone magazine.

“Rolling Stone built me. It was an extraordinary beginning, learning how to be a photographer. I grew up with the magazine, the magazine grew up with me; we all grew up together,” she adds.

Embedding herself in their worlds, Leibovitz shot candid, raw images of musicians, actors, and writers as they reshaped American culture. Her turning point came in December 1980, when she photographed John Lennon naked and curled up around Yoko Ono hours before his assassination. That image remains one of the most searingly intimate ever taken of a celebrity.

By the 1980s, Vanity Fair and Vogue had offered her new platforms where she created elaborate tableaux that combined portraiture with film and fashion, and redefined what a celebrity portrait could be: Demi Moore appeared nude and pregnant; Olympians posed as modern-day demigods; and a portrait of the Obama family for the White House was both intimate and iconic.

Today, her reputation precedes her when she works with the rich, famous, and powerful. “There’s a built-in extension of trust,” she explains. “We’re all working towards taking a really good photograph. But it’s never easy. Every single time has its own set of problems to solve.”

Even so, Leibovitz resists dividing her work too neatly. Preparing personal projects is not so different from preparing for commercial projects, she says. “I rely on my own point of view and bring it to the table. I’m interested in the commercial landscape and I try to bring something that feels personal because I think it’s territory that’s not developed enough. “I was brought up as a fine art photographer and I still try to apply that to every single thing that I do.”

Although portraits dominate her public image, quieter subjects have long accompanied them. Even in portraits, she notes, landscapes are made by looking for locations. “I don’t like to call them backgrounds—they develop as their own world.”

This interplay was highlighted in the Monaco exhibition, where still lifes and portraits spoke to one another across time; landscapes echoed interiors. There was no linear effect, but rather an associative one—a visual stream of consciousness.

In her work, Leibovitz blurs the line between photographer and artist. “I’m an artist and I’m a photographer,” she insists. “I can’t separate them. I’m proud to be both. Why wouldn’t someone want to develop all these different ideas photography has to offer? Especially digitally, a whole new set of possibilities are fascinating to me. I’ve been privileged to work with all of these ideas.”

She continues to embrace new tools with an open mind. From medium-format cameras to iPhones, all are extensions of her vision. “It’s about content. It doesn’t matter what you’re using—it is about what you are saying.”

At 75, Leibovitz’s legacy is double-edged. In her unforgettable portraits of the world’s most celebrated figures, she has transformed photography into a hybrid of art, journalism, and cultural storytelling. She is working on an archive book series to preserve the chronology that shapes her storytelling. But she remains restless, curious and engaged with the present.

“I’m still recording my time,” she concludes. “It’s a very difficult moment in the world, and I’ve been trying to figure out steps I can take to make things better.”