For four days in October last year, an exhibition dedicated to A. Lange & Söhne’s first scandalous watch, the Zeitwerk, occupied the Ion Orchard atrium. Although its digital display was inspired by a 19th-century Dresden clock, fans of the German watchmaker’s neo-classical watches were stunned to see something so brazenly “modern” when it was first unveiled in 2009.

But as divisive as the Zeitwerk’s design was, there was no questioning its pedigree. “A strong design will polarise and I accept that,” shared CEO Wilhelm Schmid at the opening of The Mechanical Masters showcase. “The only thing I will fight is when people say [the Zeitwerk] is not a Lange. The amount of craftsmanship it has, the way we assemble and decorate our movements, the technical purpose—it’s a Lange through and through; it just looks different.”

Schmid believes collections like Zeitwerk are critical to the longevity of traditional brands like A. Lange & Söhne, which has nearly 177 years of history behind it. Deviating from the formula allows for creativity and experimentation, just as the Odysseus did in 2020. It was the brand’s first stainless steel watch and its first bracelet watch. There was, of course, some resistance to it. “I saw comments like, ‘I absolutely hate this watch, it is not Lange’. However, the Odysseus is our playground. It gives us the freedom to do things we wouldn’t do with other collections,” he said, referencing the new Odysseus in titanium—another material first for the brand—that was released earlier last year.

Compared to more conservative collections like the Lange 1 and 1815, the Zeitwerk has fewer variants, but the ones that exist pack serious horological muscle.

Schmid admitted he thought the Zeitwerk would be a “monolithic watch”, a one-off experiment with no plans to further its legacy when it was first conceptualised. “However, we realised it had so much power that we could play with extra complications, and out came the Striking Time, the Minute Repeater, and the Date. It wasn’t planned as a family. It just evolved into one over time.”

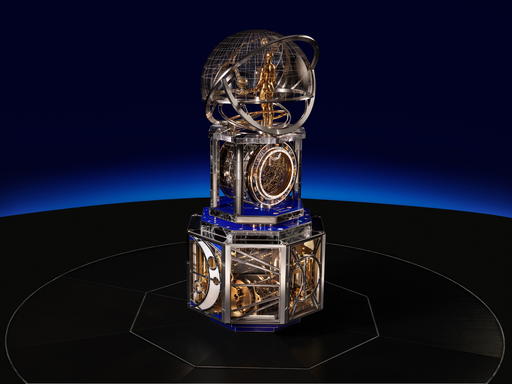

Photo: A. Lange & Söhne.

The Zeitwerk family recently welcomed its newest member, a second-generation version of the time-only original. The brand-new L043.6 calibre has a 72-hour power reserve, thanks to a patented barrel design with two mainsprings and a new pusher that allows independent hours adjustment. There are 451 components in the movement (up from 388), and each is hand-finished—even those you can’t see though the sapphire crystal case back that offers a decent view of the whole thing. Among the minimal aesthetic changes are a larger seconds subdial and a slimmer case thickness of 12.2mm. The case is crafted in rose gold with a black dial or in platinum with a silver dial.

“You won’t notice the differences unless you put the first Zeitwerk next to the new one, and that’s on purpose. It’s like the 1967 Porsche versus the 1968 version—only experts will know the difference,” shared the classic car-loving Schmid. “We also didn’t want the first-generation Zeitwerk to look old next to the new one. They have to co-exist. It’s a tricky balance, but you don’t buy a 100,000-Euro (S$143,000) watch for fashion.”

Photo: A. Lange & Söhne.

Appealing only to experts is a strategy that flies in the face of bloated profits. A. Lange & Söhne makes only around 5,500 watches a year, mainly due to necessity. Many of these processes require a skilled hand, and each collection has a dedicated team. Since watchmakers need years to master movements, Schmid cannot simply pull a watchmaker from the Datograph team to work on the Lange 1, for example. Even if he could, he wouldn’t. “The majority of people who know about us are experts, but we are becoming more wellknown every day,” he said. “How do we maintain that ‘secret society’ element while growing? Because of our relative brand unawareness, this is a permanent challenge for us.”

Schmid’s biggest challenge isn’t ironically lamenting his company’s popularity. It is getting new talent, and that is something the whole industry faces. “Young people are now growing up in a world where the life cycle of a product is six months. Everything is instantly available, the time is visible everywhere, and people work intellectually rather than physically. And we are all working in remote areas. Le Sentier, Le Locle and Le Brassus are not exactly hotspots,” he laughed, referring to the watchmaking hubs that brands like Jaeger-LeCoultre, Rolex and Audemars Piguet call home.

“The only thing I will fight is when people say [the Zeitwerk] is not a Lange. The amount of craftsmanship it has, the way we assemble and decorate our movements, the technical purpose—it’s a Lange through and through; it just looks different.”

Wilhelm Schmid

At least now that the world has reopened, Schmid can bring members from the watchmaking and decorating team around the world on these travelling exhibitions to add some adventure and variety to their otherwise quiet lives on the craftsmen benches. Master Watchmaker Robert Hoffmann and Master Engraver Robert Arnold were at the Mechanical Masters showcase to demonstrate their skills and answer questions from eager fans and neophytes alike.

Even though Schmid’s priority isn’t to rapidly increase production and make gobs of money for the company, he remains confident about his careful strategy and is optimistic about A. Lange & Söhne’s future. “The good news is that our foundation is so strong that no CEO can derail the company,” he quipped. “We think long-term because it stops us from being too opportunistic. As long as we are controlled, sustainable and profitable, we will not fail.”