In the hands of the visionary Philippe Starck, everything becomes poetry. Even the iconic Perrier bottle is reimagined as a Fresnel lens in a lighthouse, an ode to his love for sailing. But the striated pattern goes beyond aesthetic purposes; they’re a solution to Starck’s childhood fear of letting the bottle slip out. He once clutched it so tightly it hurt. “The bottle clings to me, I cling to the bottle: another form of play. You’ll see it, in this new bottle, the bubbles are out of this world,” he says.

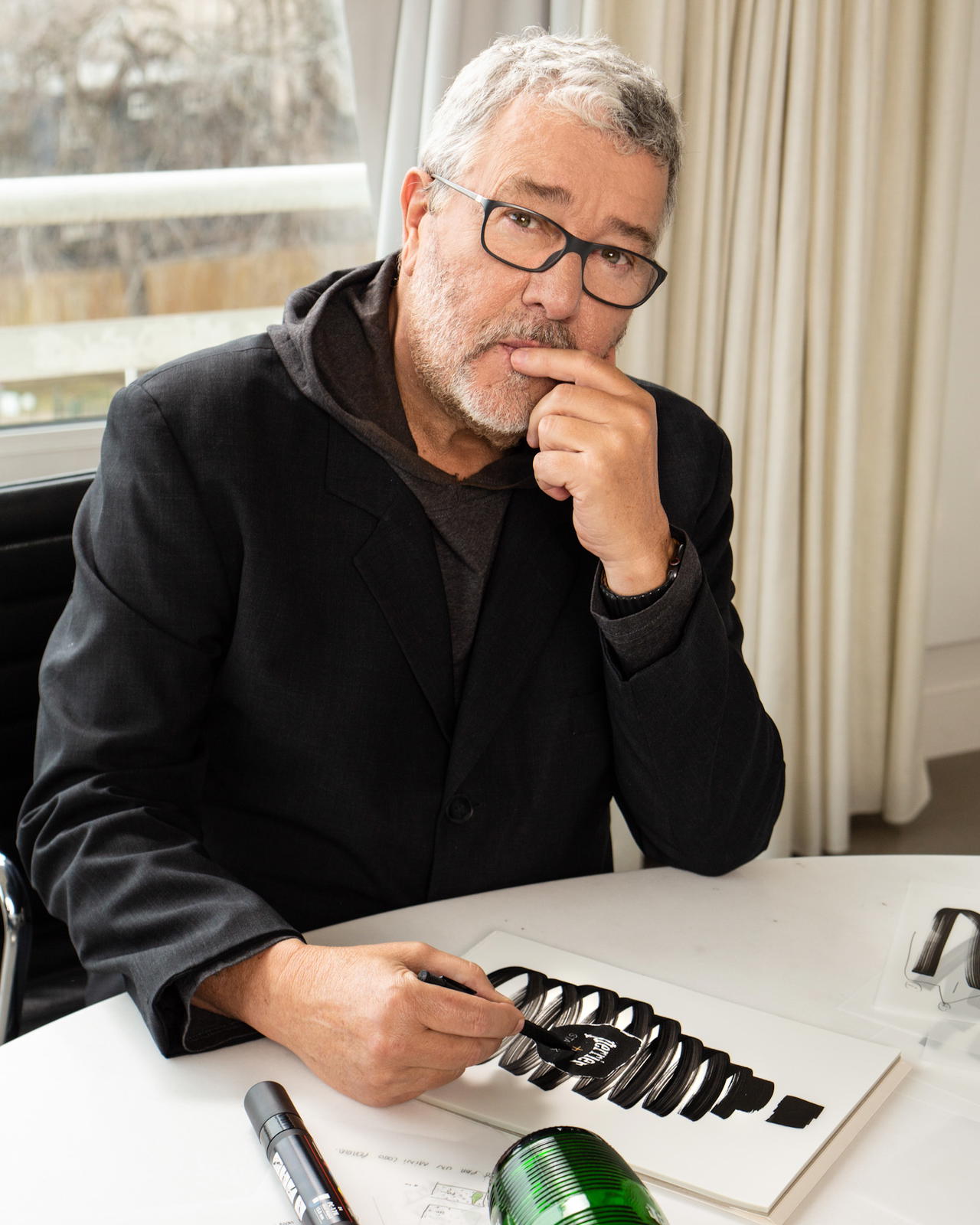

We chat with the French industrial designer and architect about his recent collaboration with Perrier, his design philosophy, and why he considers himself “nothing more than a creative machine.”

Congrats on your collaboration with Perrier! Could you tell us how this came about?

This collaboration is part of Perrier’s 160th anniversary. I was honoured. Working on the Perrier bottle is like being asked to reimagine the Eiffel Tower. These are world-famous icons, yet they are profoundly French and deeply sentimental.

Could you walk us through the design process of the Perrier + Starck bottle?

It took over three years of work to create the new bottle. The brief was extremely precise: nothing was imposed on me, and everything was impossible. The challenge was to be humble to respect and celebrate this icon. I focused on the minimum of things, the bone of the subject.

As a sailor, the sight of a lighthouse has always captivated me. This gave me the idea of applying the Fresnel lens to the bottle. Through it, we see reflections, diffraction, and aberrations. These extraordinary optical effects bring about a poetic dimension.

What’s the most challenging part about reinventing such a recognisable bottle design?

When you are lucky enough to work on an icon, you cannot imagine changing it, neither shape nor colour. However, you can play with it or twist it. As a creator who expresses himself in three dimensions, I wanted to amplify the sentimentality by playing with the glass of the Perrier bottle to create optical tricks through the bubbles.

You’ve designed plenty of iconic products in your career so far, like the Louis Ghost chair and the Juicy Salif juicer. Which is your favourite and why?

I never look at the past because I cannot remember anything. We should never look back, except to verify something that has already been acquired and on which we continue to build. We must take part in our permanent mutation and evolution. I am working on 250 projects at the same time, constantly looking forward.

Naturally, my favourite project is the upcoming one. I follow the same process: a project deserves to exist if it benefits the user, whether material or immaterial. For example, the Louis Ghost chair talks about our collective occidental memory of a chair.

You’ve been described as a “forward-thinking genius” and a “brilliant designer”. How would you describe yourself and what you do?

I consider myself a dreamer, an adventurer, and an explorer. I always create with the highest level of honesty. If design does not save lives, it can somehow improve lives. My only motivation has always been the profit of the person who will use the things or places I create.

What is good design?

Design products are made to live with. Functionality is key. Culture and aesthetics do not count for me, because I am not an artist. I use materials, shapes, and colours, to reflect what my community, my family, or even myself want and need.

One rule of elegant functionality is to find the centre of the project, the backbone, and the minimum. When you have found the minimum, you can guarantee that it will be timeless. Useful and honest design results in a timeless product. It is created with materials of the highest quality to ensure its longevity.

You once mentioned in a Harvard Business Review interview that you “never collaborate—not because you don’t like other people but because you are not able to do it.” Why the change of mind with this Perrier collaboration?

I have collaborators of course, an amazing team that I work with. I do not delegate or work in a group. I always design everything alone. When I share a project, my team receives it finished; there is nothing to do except to crystallise and computerise it.

Beautiful projects are like having children, partners must be in love. After many years of creation, I am lucky to be able to choose the projects and partners I want to work with. It is important to work with the good ones, the ones who come to you with a real vision, who use their savoir-faire to be of service. To me, venality is unthinkable, and people with a real vision are indispensable. The other qualities are intelligence, sympathy, openness, and liveliness. Perrier ticks all these boxes.

What’s your ideal environment to design in and why?

My wife, my daughter, and I live near Sintra in Portugal, in the middle of nowhere, surrounded by nature. The more materiality, the less humanity. I cannot create in cities. We do not go to the movies, cocktails, or dinners. I have no connection with reality. I work alone on a small table, with my Japanese criterium and my tracing paper. The only thing I do is create. I reach a high level of concentration, which enables me to produce a huge number of projects in very transversal territories. I am nothing more than a creative machine, and everything around me is organised so that the creativity runs smoothly. 14 hours a day, every day of my life.

What do you foresee as the next big design trend and why?

I don’t believe in trends because a trend is a recent idea. We think it is eternal, but everything has a birth, a life, and a death. It is urgent because when you make something trendy, it means it will soon no longer be. The trend is what one throws away. To create something a little bit new, you must avoid being mainstream.

On the other hand, design doesn’t have much of a future, given that it is a producer of materials. The future does not belong to the production of materials. Dematerialisation and bionism is the only way to evolve, to be more of us.

The interview has been shortened and edited for clarity.