No matter where one grows up in, it’s almost a cross-cultural phenomenon for a man to have his first grown-up tailoring moment at a certain point in his life. For me, it was for a junior college formal. It wasn’t my first time wearing a suit; it was the first time that I went to a tailor, picked out the colour and fabric I wanted my suit jacket to be in, and got measured for it.

The idea was to wear a cream-coloured blazer—a colour that I was very certain no one would have thought of. It wasn’t luxurious in any shape or form, given that it was a polyester-blend material and lined with more polyester. But I knew the details that I preferred based solely on my idea of contemporary fashion back then. I didn’t want shoulder pads, I wanted my buttons to be colour-matched to the main fabric, the shoulders to be slightly roped, and that the fit to sit somewhere between slim and regular.

It was an old-school tailor shop at Lucky Plaza decorated with suits—that were bordering on tacky—on mannequins surrounding the space, as though to showcase their most outré capabilities. I was a tad apprehensive but thankfully, the blazer turned out as requested. I felt grown up. To be able to wear something that was fitted to me and to some level of personal customisation felt like one of the first steps towards manhood.

There’s little doubt that therein lies the emotive quality of menswear tailoring. Except for shirts and trousers, suiting still is often regarded as occasionwear especially as it’s increasingly becoming less necessary in the everyday context of society.

The history of men’s tailoring dates back to beyond 1600s Europe from where the first instances of modern suiting and tailoring were then adapted. While tailoring is now widely available to almost everyone, custom clothing then were only afforded by royalty and nobility with craftsmanship focused on using the most exquisite of fabrics. Tailoring was used as a sign of power and dignity, very clearly dividing the different classes of society. Hence, it was little wonder that tailoring styles were incredibly excessive and consisted of multiple layers. Tailored adornments such as ruffs, broad lace collars, and breeches added on to the distinguished styles of the time, further accentuated by heels (yes, for men) decorated with shoe roses and other manner of embellishments.

Towards the 17th century, the ornamentation began to slowly dial down. It was almost de rigueur that life in the West was heavily governed by politics and religion. Three different factions grew dominant based on their differing ideals—the Cavaliers, Roundheads, and Puritans.

The Cavaliers were named after well-dressed soldiers who fought in support of the Catholic King Charles I in the English Civil War and were thus linked to Catholicism. The Roundheads were the opposing faction who supported England’s governing body and more Protestant religions, while the Puritans were their offshoot but stricter in ideals of wanting zero excessive displays of self.

At the same time, a burgeoning wealthy middle class were seen as disruptors to the social class delineation that the nobles were used to. The Industrial Revolution too made creating custom clothing even more affordable than ever and simpler suits gained popularity for their practical ease, comfort, and of course, cheaper production costs—as exemplified by the Victorian and Edwardian eras and a period that collectively became known as the Great Male Renunciation.

There were no longer any flou in men’s dressing and tailoring was relatively much more rigid than the years prior. It was the beginning of tailoring becoming stuck in gendered convention. Changes, if any, were very minor.

But if we’ve learnt anything in fashion, is that it all comes back around. Attitudes shift a fair bit in fashion albeit in menswear’s more glacial pace. Staid tailoring eventually made way for more exciting hues and cuts thanks for the 1960s where the rise of countercultures grew more prominent in the West. The Mods and hippies—although differed in attitudes and outlooks of life—were brimming with self-idealised sense of identity that were far from the mainstream. There was once again a creative resurgence and tailoring took the form of sleek Italian but mixed with more utilitarian pieces for the Mods, while the hippies embraced colours as well as floral and psychedelic prints.

As lifestyles began to relax in the 1970s, so did the fashion. Tailoring started to be paired with more casual separates, essentially breaking the suit. It wasn’t unusual for a formal velvet tuxedo jacket to be worn with something as casual as polyester slacks. Giorgio Armani was a powerhouse and cemented the look of the decade: unlined suits with zero padding and with an intentionally looser fit all over so that sleeves could be easily pushed up and trouser hems folded as needed. Everything—ties, collars, and lapels—were designed narrow and, a lot of the times, were left undone for a rakish appearance.

The decades after were continued riffs on the high-low styling in terms of formalities of dress. It wasn’t as though tailoring was completely dead; the idea of tailoring became far removed from any of its traditional notions. Sure there was power suiting that was a 1980s favourite, but beyond the professional setting, more leisurely proposals reigned supreme.

The most significant evolution in tailoring that proceeded came in the form of Hedi Slimane. At the creative helm of Yves Saint Laurent’s Rive Gauche Homme line, Slimane’s autumn/winter 2001 was a prelude to what remains his signature—skinny-everything tailoring. A love for Mick Jagger-era rock and roll prompted the hard-to-get-into silhouette that became a revolution. Slimane was even cited for being the reason the late Karl Lagerfeld lost about 42kg to fit into his Dior Homme suiting.

Not only was Slimane changing the way tailoring fit, he also opened the doors for a more gender-blurring approach to tailoring. The hyper sexualised rock and roll edge characterised by sheer fabrications as well as chest-baring tops was heightened the moment Alessandro Michele of Gucci came into prominence in 2015. At a time where gender norms were being challenged by a whole new generation, Michele interpreted it by softening tailoring—rounding shoulders, hems and opting for silk crepes and georgettes as nods to more fluid moments in fashion.

The gender-blurring aesthetic hasn’t stopped since. Michele may have left Gucci but the torch has been passed on to a slew of independent fashion designers who have championed men’s tailoring from the very foundations of their labels, and deconstructing them for the now. Adding in typically feminine flourishes without a care for traditional norms is a similarity.

It’s a clear reflection of today where men are more than just their socially constructed masculine ideals. Malaysian-born fashion designer Sean Suen captures this beautifully with collections that focus on menswear tailoring but elevated in non-traditional ways. For his spring/summer 2023 collection, a hangover-inspired collection sees traditional swathes of blacks, whites and creams interspersed with feminine laces and sheer fabrics juxtaposed with oversized tailoring in a play of textural tensions.

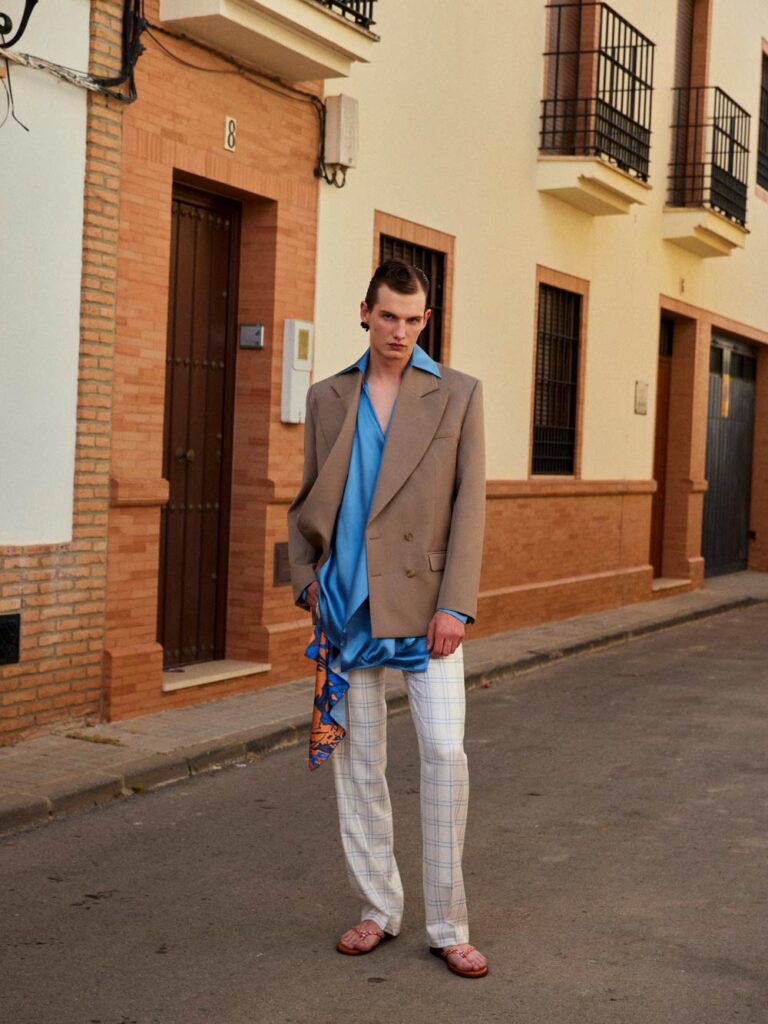

Similarly, Spanish brand Mans roots itself in classic tailoring references and Savile Row craftsmanship, combining them with cultural references The results are often vibrant and colourful, just like its spring/summer 2023 collection that captures a man unapologetic of his neo-masculinity.

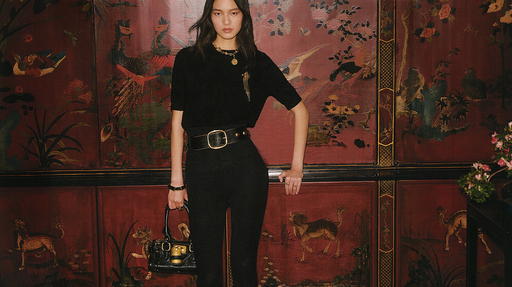

Then there’s Highlight Studio’s more casual take on tailoring by showcasing its versatility beyond formal occasions and how that they can be cut the same for women as well through boyish constructions.

The thing is, I could still dig out that very same cream blazer that was made for me 15 years ago and it would still be able to fit in today’s context. It’s not because I was in some way skilled at ascertaining evergreen design nuances, but rather, the evolution of menswear tailoring is hardly on par with that of women’s fashion.

But having said that, the fact that evidences of different kinds of menswear tailoring still remains, exemplifies just how important tailoring is in the menswear universe. The suit may never actually die, at least not entirely.

Where will tailoring go next? There’s no telling, really. But if we take social gender constructs as a gauge, hopefully it’s to where a suit is more than just a symbol of masculine ideals.