In the rolling countryside of County Cork, Ireland, past hedgerows and winding lanes, an 18th-century farmhouse in Fartha hums with the sound of hammers, chisels, and sanders as hands coax wood into improbable shapes that split and then converge, giving the sensation of movement.

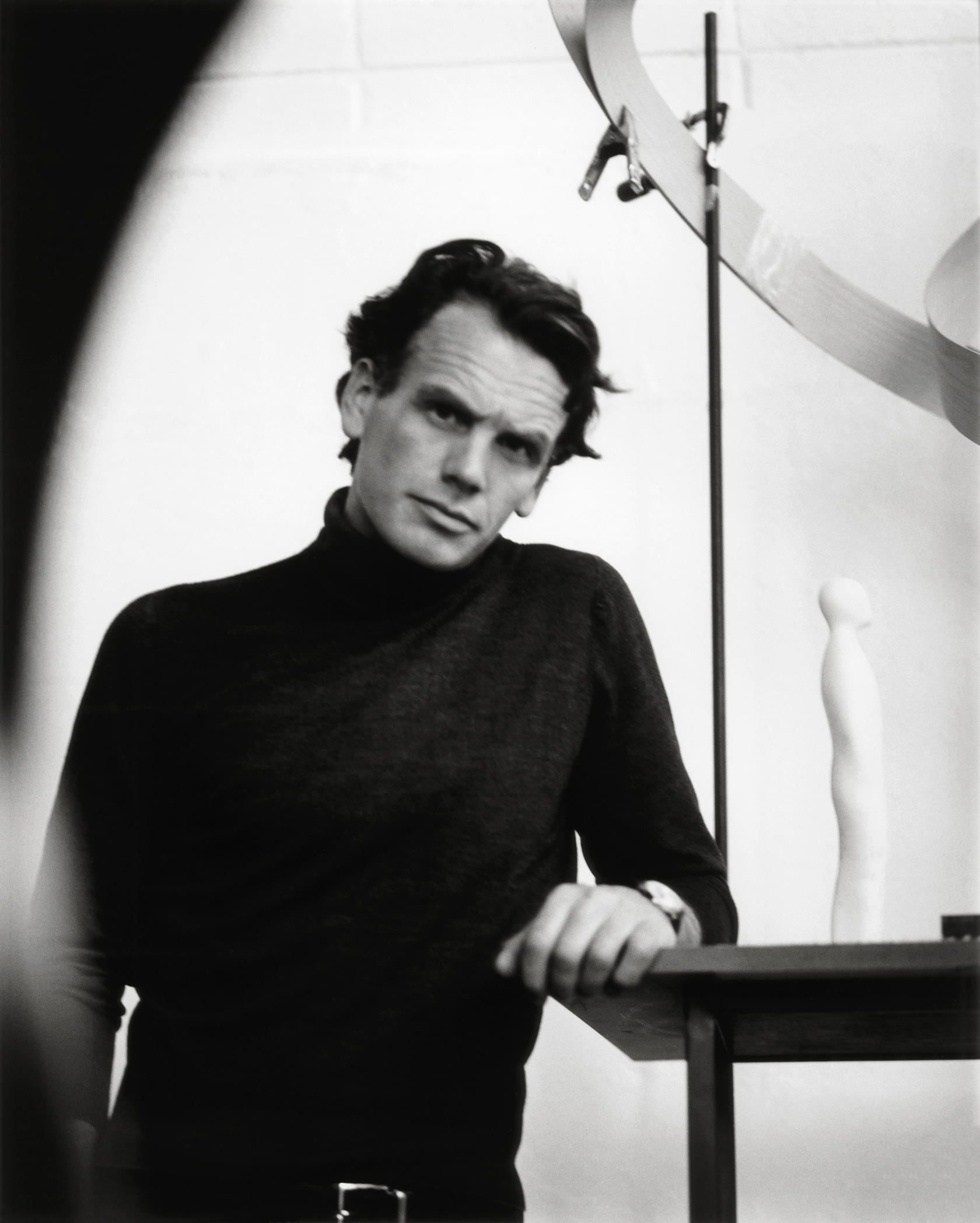

This is Joseph Walsh’s studio, founded when he was 20 years old. It began as a young man’s desire to make things and has evolved into one of the world’s most respected design studios. Amidst sweeping loops, swirls, ripples, and ribbons of oak, ash, and walnut, one senses that he is not simply shaping furniture or sculpture. It is an experience, an invitation to inhabit form as a gesture suspended.

from farm to form

Walsh was born in 1979 on this farm, surrounded by people who made everything they needed: gates welded by neighbours, leather shoes and schoolbags made by the cobbler, and more. These rhythms of life shaped everything that came afterwards: “I grew up on a farm and was lucky to see a world where people still made and fixed things.”

Before mass industrialisation swept rural life, improvisation was an inherited culture in agricultural Ireland. “Having something made today is a luxury. When we were young, it was a luxury to buy something. It was normal to make it,” he says.

By the time he was 12, Walsh had already built a dresser from scratch. He charted his own course after dropping out of school without formal training. “Starting to make things with your hands when you’re so young gives you an advantage,” he admits. “You have muscle memory and things come naturally to you. Success in making something [when you’re] young enough gives you this incredible feeling of empowerment and humility at the same time.”

He visited master makers around Europe, absorbing techniques and ideas, then returned to Fartha to experiment. It was never about replicating traditional craft, but about discovering possibilities. This instinctive, boundary-pushing still defines his studio.

The turning point came with Enignum, his series of wooden tables, chairs, beds, and sculptural works with flowing lines that feel grown rather than constructed. Breaking convention, Walsh abandoned geometry by bending thin layers, taking them off benches and formers, and allowing the wood to dictate the shape and the atmosphere to clamp the piece, instead of carving the wood out.

“At first, I tried to control the curves, but after a solo show on Fifth Avenue in New York in 2008, I threw the rule book out and decided to work freely,” he says. The results were intuitive, organic, and unlike anything seen before. Compared to rectangles imposed by industrial saws, curves are more natural. “Trees don’t grow as planks,” Walsh argues.

Even though he works with a wide range of materials, including transparent resin, marble, and upholstery, his work is a meditation on wood’s inherent qualities— strength-to-weight ratio, sustainability, delicacy, and monumentality. He still remembers the gift of trees from a farmer when he was 15: “This wood was like treasure to me. I knew each tree and each plank.”

That intimacy with material remains central to his practice.

AN UNHURRIED ETHOS

Unlike industrial designers who license forms to manufacturers, Walsh manufactures his furniture in-house. The Irish, Japanese, and Italian artisans on his team collaborate with specialist foundries, glassblowers, and aviation engineers to push the limits of technological feasibility. “The big breakthroughs come from the fact that I make the pieces here, without being limited to a production line.”

The studio’s ethos is unhurried, deliberate, and deeply human. Timber is purchased at least five years in advance and allowed to dry. Clients are guided through patient processes that can take years, but produce objects meant to last for generations. In Walsh’s words, “If you create something with energy, beauty, and intelligence, nobody wants to give it up. Its life goes on and on—as long as somebody restores it, sells it, or buys it.”

Walsh stands out from the gallery system that dominates much of contemporary design by focusing on private commissions, with collectors spanning continents. They include Japan, South Korea, China, Singapore, India, Greece, Italy, Austria, Switzerland, Canada, the US, Argentina, Uruguay, Peru, and the UAE.

beyond the studio

From liturgical commissions for Irish churches to a 6-m dining table and 20 chairs for the Japanese embassy in Dublin, as well as one-off art pieces and ambitious architectural collaborations, his reach is astonishing.

His creations are in the Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York), The Centre Pompidou (Paris), and Chatsworth House (England). Through Tokyo-based gallery A Lighthouse called Kanata, his work travels to Shanghai for the West Bund Art & Design fair this November, and to Art SG in Singapore in January 2026.

His first monumental outdoor sculpture, ‘Magnus Rinn’, was unveiled at Expo 2025 Osaka. This milestone piece is made from gilded bronze and oak, and it combines Irish aerospace lamination technology and Italian foundry craftsmanship. The installation marks the conclusion of Walsh’s seven-year research and the beginning of a body of exterior work.

Closer to home, he is prototyping a “maker’s house”—an experimental architectural project inspired by vernacular forms, built with natural materials but designed for modern living. In addition, he will erect his largest outdoor sculpture—a bronze and wood composition standing 10.5m tall—on the grounds of Adare Manor, host of the Ryder Cup in Ireland, in 2027.

Rather than just being a place for making, Walsh’s studio is an environment in which dialogue takes place. Every September, he convenes Making In, a gathering of makers, architects, performers, economists, monks, and growers. “The same group wouldn’t have the same conversation in a museum or city,” he notes. It’s the workshop environment—a space for imagining and creating—that sparks conversations. These discussions, in turn,

feed back into the workshop, creating a continuous cycle of inspiration and innovation, he explains.

He believes such exchanges nourish not only his own practice, but also a broader appreciation of how things are made. “Our parents or grandparents would have been connected to some form of making, but as we have become more consumer-oriented, we’ve become detached from how things are created. It’s a real reflection on society that utilitarian tools were made so well during their time, and now they’re made so poorly.”

The farmhouse in Fartha, where it all began started, still anchors Walsh. It now serves as a home for a dedicated team, a vibrant community, and a philosophy that views making not just as a skill, but as a way of life. The ultimate goal of his practice is to slow down, work with the seasons, let materials breathe, and allow ideas to mature.

Hours and years of sketching, bending, laminating, and finishing go into each creation. In an age of instant consumption, he offers something rarer—permanence.