It was 2013. A one-way ticket around the world led Christopher Leow to New South Wales, Australia, where he stumbled upon a self-sustaining farm with an assortment of livestock and crops, rainwater harvesting and off-grid power generation. He liked it so much that he stuck around for three months as a volunteer.

Leow returned to Singapore inspired to learn more about farming. There was just one problem. “Back then, formal education in agriculture didn’t exist,” recounts the 37-year-old. So, he developed his green thumb by participating in local farming initiatives and growing produce in unused spaces such as rooftops and multi-storey car parks. He also travelled overseas frequently for learning stints.

With diligence the mother of good luck, he received a job offer in urban farming in 2016. His first task was to lead a team to establish a flagship farm at Edible Garden City, Singapore’s first circular and community-commercial farm and social enterprise. “It was difficult to turn down the offer despite the low salary back then because it was a wonderfully meaningful venture,” he says.

While he has since worked on other farming projects, he considers that endeavour to be the most memorable. “We encountered all sorts of craziness, as any farm would. There were floods, crop failures, and pythons eating our chickens.”

Despite our limited land space and constraints as a city-state, urban farming in Singapore is diverse, says Leow. On the grassroots level, there are homes with pots of culinary herbs, community gardens, schools with urban farming programmes, and offices with indoor micro urban farms. Then, there are commercial farms that grow vegetables on HDB rooftops and boutique farms that cultivate mushrooms in industrial estates.

But while it has healthy representation, it is not without challenges. First, not only is land at a premium, urban farm plots have to compete for space with things like solar panels. Second, free space isn’t necessarily able to bear the load of an urban farm, especially in older buildings. Lastly, ignorance is still pervasive. “As a country, we have become so disconnected from our food system that farming is perceived as ‘low class’ or dirty,” explains Leow.

“Since we have an abundance of food on our shelves, we don’t see the value of growing our own. To me, this is the biggest hurdle we need to overcome.”

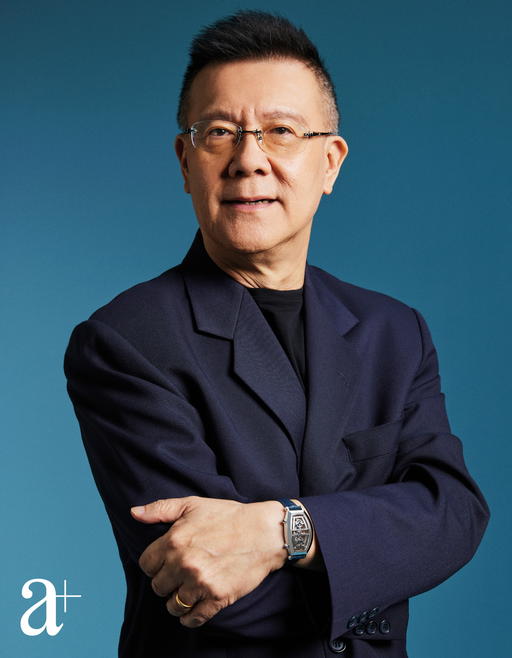

Christopher Leow on a key stumbling block in urban farming

Last year, he founded urban farming consultancy The Freestyle Farmer. Its aim is simple: help people become confident in navigating the complexities of growing food. Thus far, he has worked with several entities including households, schools, hospitals, and restaurants to transform urban spaces into functional, biodiverse, and aesthetically-pleasing urban farms. Apart from hosting the CNA docuseries Growing Wild, Leow also lectures at Republic Polytechnic on topics such as agribusiness risks and organic farming methods. He released a book in 2022 which chronicles his journey of becoming an urban farmer in the city.

His advice for growing our own food? We ought to look beyond yield numbers because they don’t actually mean anything. A bigger yield just means the plants are storing more water, so it is heavier. It doesn’t mean they are better.

As much as possible, farming should be a communal activity. The elderly can lend their knowledge in culinary applications while young adults can lend physical strength. It’d also be ideal that we incorporate growing food into our lifestyle. “We’d be able to create a much more resilient and powerful food system,” affirms Leow.

Art director: Ed Harland

Videographer: Alicia Chong

Photographer: Mun Kong

Photographer’s assistant: Hizuan Zailani

Hair: Aung Apichai using Kevin Murphy

Makeup: Sha Shamsi using Chanel Beauty