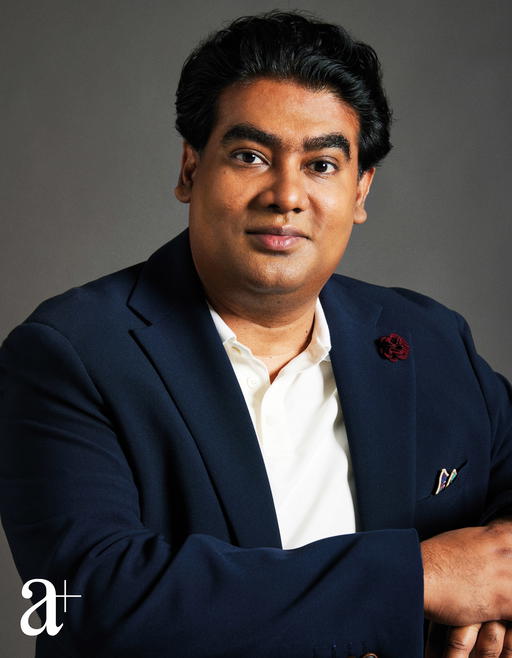

A common misconception about the blind is that they don’t see anything at all. But vision impairment exists on a spectrum, so even after getting diagnosed with Stargardt disease at the age of eight, Cassandra Chiu could still read with a magnifying glass. It is only because her condition has deteriorated that she can now, at best, tell whether a room is lit.

But Chiu doesn’t take a dichotomous view of her vision loss. “What I could see then versus now doesn’t make me more or less blind,” she says. “The challenges and the tools I use to navigate them are just different. What remains constant is the need for creativity and problem-solving, whether independently, with support from others, or with my guide dog.”

In 2011, Chiu became the first woman in Singapore to be a guide dog handler when she received her first guide dog. She received her third and current guide dog nine months ago, but withholds its name publicly as a precaution. “This prevents people from calling out to it while it is working, which can distract it. It’s something I experienced with my previous dogs,” she explains.

In 2020, she founded K9Assistance to promote the acceptance of all types of assistance dogs. The charity not only advocates for guide dogs for the blind, but also for mobility assistance dogs for people with physical disabilities, hearing dogs for the deaf and hard of hearing, and autism assistance dogs for autists. Chiu’s efforts have borne fruit.

“In the past, people didn’t know what assistance dogs were. It was rare to see one on public transport. Now, I hear children explaining to their elders that my dog is allowed on the MRT because it is working. The shift in public awareness matters.”

Cassandra Chiu on increased social awareness

In addition to being an ardent advocate for equal opportunities for persons with disabilities, she is also the president of the Disabled People’s Association. Because her roles at K9Assistance and Disabled People’s Association represent governance and management respectively, she is able to acquire insight into different charity functions, she explains. “Understanding the board’s strategic priorities helps me make better operational decisions. At the same time, my frontline experience allows me to shape long-term plans that affect service delivery.”

Her social responsibilities are on top of her work as a psychotherapist, where she primarily works with couples to improve communication, reconnect, and navigate difficult times in their relationships.

In spite of the hoops she’s had to jump through as a visually impaired person, Chiu is grateful for infrastructure like tactile markings and audible traffic lights—a sign of Singapore’s inclusivity.

That said, she reckons there is room for greater empathy. “People may feel sympathy, but that’s not the same as understanding. One of the biggest challenges I face is what I call the ‘societal handicap’. It’s when people make assumptions about what I can or cannot do just because I’m blind, which can be more limiting than the blindness itself.”

She recounts an incident in which she was turned down for a job. “They said, ‘You’ll need to work late and it gets pretty dark at night here, so we feel it might be dangerous for you’. But I’m blind, so light or dark makes no difference.”

Chiu hopes for a continuous shift in mindset. In her experience, disability is often viewed through the lens of pity or limitation rather than potential and equality. She also believes that we should refrain from viewing accessibility as an act of kindness when it is a basic right.

“The disabled are an integral part of society. Inclusion shouldn’t be about making space for us, but removing the barriers that keep us out.”

Photography Mun Kong

Art direction Ed Harland

Hair Yue Qi using GHD

Makeup Sarah Tan using Shu Uemura

Photography assistant Melvin Leong