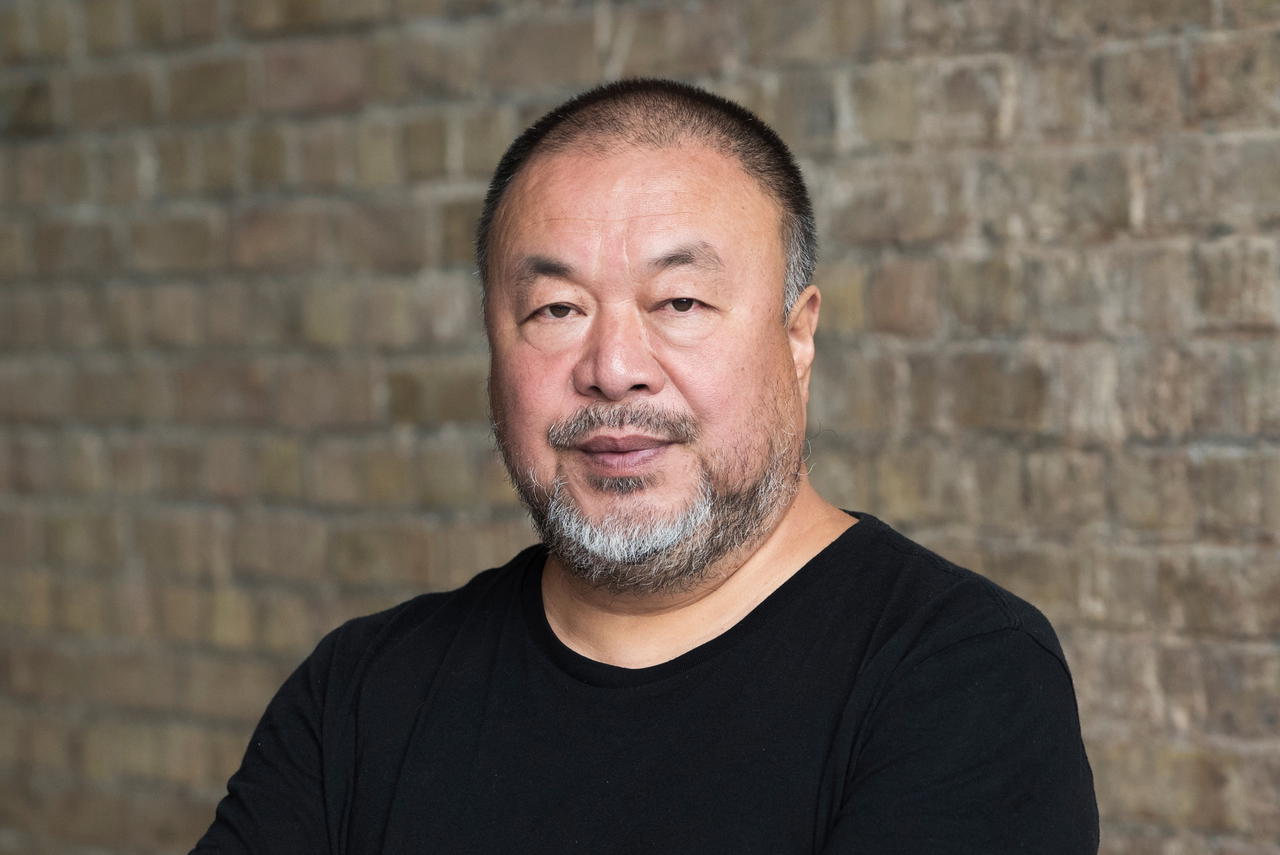

“I always tell people I’m a fake artist, but they don’t believe me, so I still associate myself with art activities. I’m happy people tolerate what I do,” says Ai Weiwei, matter-of-factly. He’s dead serious.

“It’s not that I wanted to become an artist. It was only because I didn’t want to be anything else like a banker or a business person,” he adds. “My father was a writer, so being an artist was natural. However, it was also a shortcut. I would rather be called a writer than an artist, but I am not very skilful. A poet needs to be in a more pure and innocent state. I have already messed up.”

He’s referring to his father, the great Chinese poet, Ai Qing. Communist officials accused him of being an anti-revolutionary rightist during Chairman Mao’s anti-intellectual campaign shortly after Weiwei was born in 1957 in Beijing.

As a result, the family was exiled to semi-military labour camps in Heilongjiang and Xinjiang for two decades. They were only allowed back into Beijing in 1976 at the end of the Cultural Revolution.

Ai shows me a photo of a hole carved into the ground previously used for farm animals, which he keeps as his mobile phone’s home screen. It’s a constant reminder of the underground cavern he lived in with his family for five years. His father was forced to perform hard labour, including cleaning public toilets. He picked up practical skills in his communal work detail, such as making furniture or bricks, which he would later apply to his art.

“It was extremely harsh. We had very little fruit, no meat, no cooking oil, and no electricity. Water had to be carried back from a distance. That’s how I grew up until I was in high school,” says Ai.

Exile has become a way of life for the nomadic artist, who lived in the US from 1981 to 1993 and has been in Europe since 2015, after leaving China for safety reasons, and receiving asylum in Germany. Currently, he is building a new studio in the Portuguese countryside, which will be completed this summer, while maintaining spaces in Berlin and Beijing.

We’re standing in Galleria Continua’s flagship gallery in San Gimignano, a walled mediaeval hilltop village in Tuscany southwest of Florence. It’s a UNESCO World Heritage Site and the venue for Ai’s latest solo show Neither Nor, on display until Sept 15 2024. According to him, the exhibition is named after an early work by Jasper Johns, one of his favourite artists.

“Most times, our thinking is not limited to absolute truths or single interpretations but rather exists in a state of ambiguity that encourages greater possibilities and debate. Human thought, culture, and art thrive in this state. As a result, it is often difficult to provide definitive yes or no answers. Regardless of the answer, there is a strong sense of exclusivity and a lack of tolerance for alternative perspectives.

“In today’s world, there is too much political correctness. It doesn’t allow people to think outside the cage. Humans are capable of thinking freely and asking questions. However, in many societies, even universities, this is not allowed. In the West, there is censorship as in China, but at a different level. It prevents liberal thinking and questioning.”

Ai has never shied away from poking the hornet’s nest. He speaks his mind fearlessly and believes art and activism are intertwined. In 2005, Chinese web portal Sina invited him to write a blog. He soon found it to be an effective platform for airing his criticisms of the Chinese government.

Through the blog, he distanced himself from his role in designing the National Stadium for the 2008 Beijing Olympics, also known as the Bird’s Nest, in collaboration with Swiss architects Herzog & de Meuron. He alleged that the Olympic Games were tarnished by official corruption.

When he conducted his own citizen investigation following the 2008 Sichuan earthquake, he berated officials for their negligence, which resulted in thousands of students dying in collapsed public schools due to substandard construction. This probe culminated in the installation ‘Remembering’, which saw the façade of the Haus der Kunst museum in Munich covered with 9,000 colourful children’s backpacks arranged to form a quote in Chinese from an earthquake victim’s mother.

The government quickly shut down his blog after it became popular, with as many as 100,000 views per day. So, he transferred his online presence and thoughts to Twitter and garnered worldwide exposure.

Despite this, the Chinese state continued to restrict Ai’s freedom of movement and communication. His studios in Shanghai and Beijing were razed, his home and studio were monitored by government cameras, and he was severely beaten by police. He was also jailed in 2011 after being accused of tax evasion. Global awareness of his situation and increasing diplomatic pressure from democratic countries led to his release after 81 days.

Although he was fined 15 million yuan (S$2.8 million), Chinese and international sympathisers raised the money for Ai to pay it off. In the aftermath of the incidents, international media coverage brought more attention to the outspoken artist and the authorities’ efforts to silence him backfired.

Ai asked his son Ai Lao what he thought about his father’s imprisonment. “Ai Lao said that even though I had been detained, it was okay since it was like a big advertisement for me. That’s true. I’ve become very well-known in art circles. What the Communists did suddenly put me on a broader stage. Even the secret police interrogators asked me, ‘Weiwei, without our pressure, you would never have become so well known, right?’ I said, ‘Yes, it takes a powerful state to make me become a known person’.”

Ai knows that when he comes up against an obstacle, he can rely on the public’s help. In 2015, when Lego refused to sell him a bulk order of bricks because it didn’t want its products used for political purposes, he mobilised his fans through social media. In a show of solidarity, they sent him millions of Legos via mail and official collection points.

Labelling Lego’s act as discriminatory, he points out, “It didn’t even realise it had made a political statement by not selling me the bricks. I won the case. Now I can freely use them. When it said I could not use Legos, it encouraged me to do something that seemed impossible. Globally, people supported me, but it all happened spontaneously. It’s impossible to plan such things.”

Photo: Ela Bialkowska OKNO Studio

As part of Ai’s first Lego masterpiece, 176 portraits of activists and political prisoners were displayed on Alcatraz Island in San Francisco Bay. They ranged from former president of South Africa Nelson Mandela to Burmese politician Aung San Suu Kyi. The pixelated effect resembled surveillance and Internet images.

“Using Lego gives me liberty because even though I haven’t painted since the ’90s, I’m still tempted to do 2D work,” he says of his bas-reliefs made from the tiny toy bricks resembling mosaic tiles. “While Lego is not exactly 2D, it is constructed of small sculptures and pixels. I love Lego’s childish quality, but there’s a profound political or personal meaning or artistic argument behind my works.”

Some see Ai’s Lego installations that replicate some of the most venerated works of Western art history as provocative. However, his work has never just mere copies. There’s always an insertion. In his Continua exhibition, Giorgione’s ‘Sleeping Venus’ features a coat hanger referencing self-induced abortions and the repression of women’s rights.

In Rubens’s ‘The Rape of the Daughters of Leucippus’, a panda clings to a horse as a symbol of contemporary Chinese power.

A refugee materialises in Georges Seurat’s ‘Un Dimanche Après-Midi à l’Île de la Grande Jatte’ in response to the 2022 ban on the burkini in France.

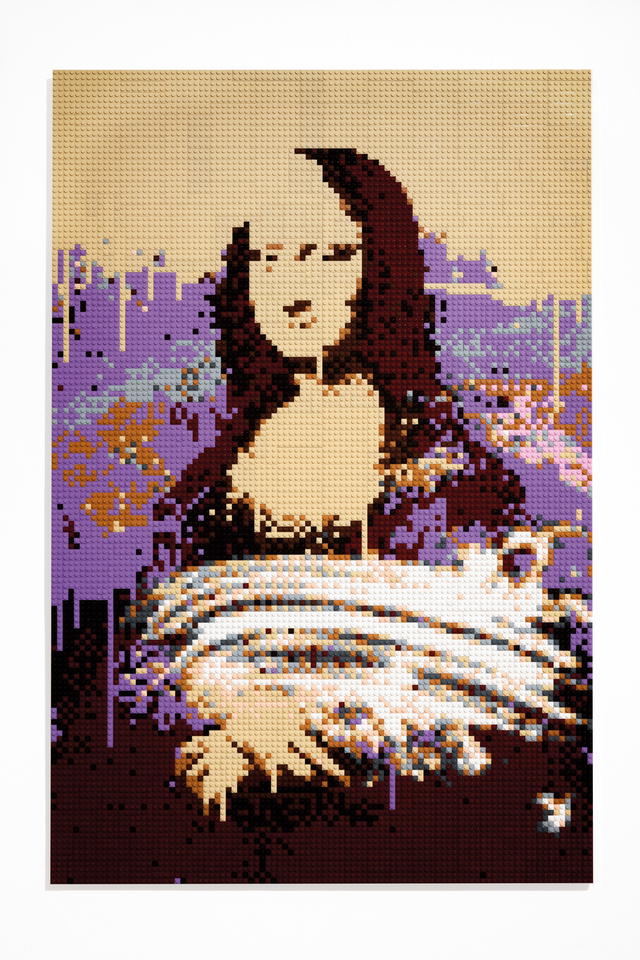

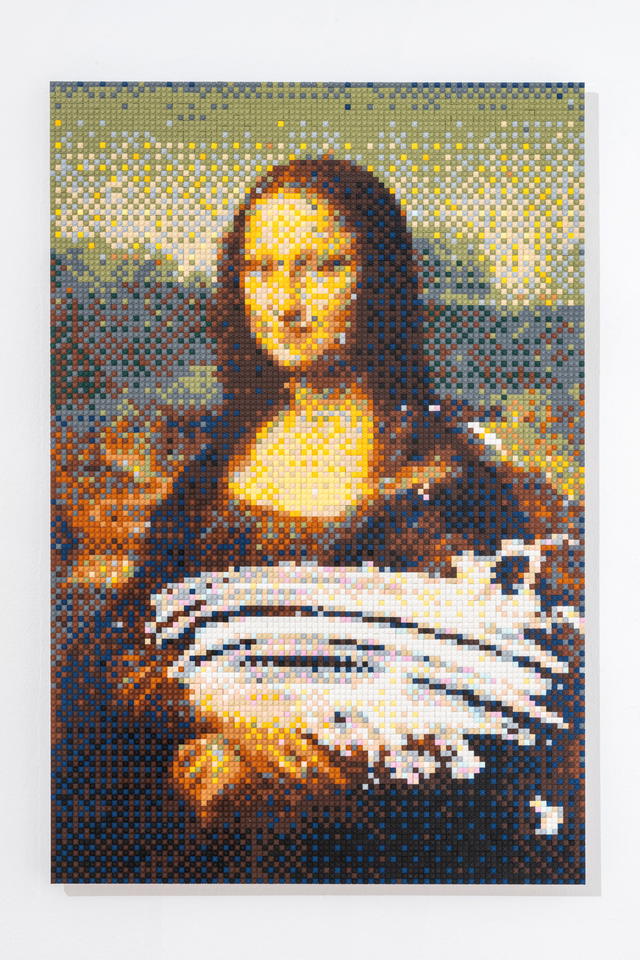

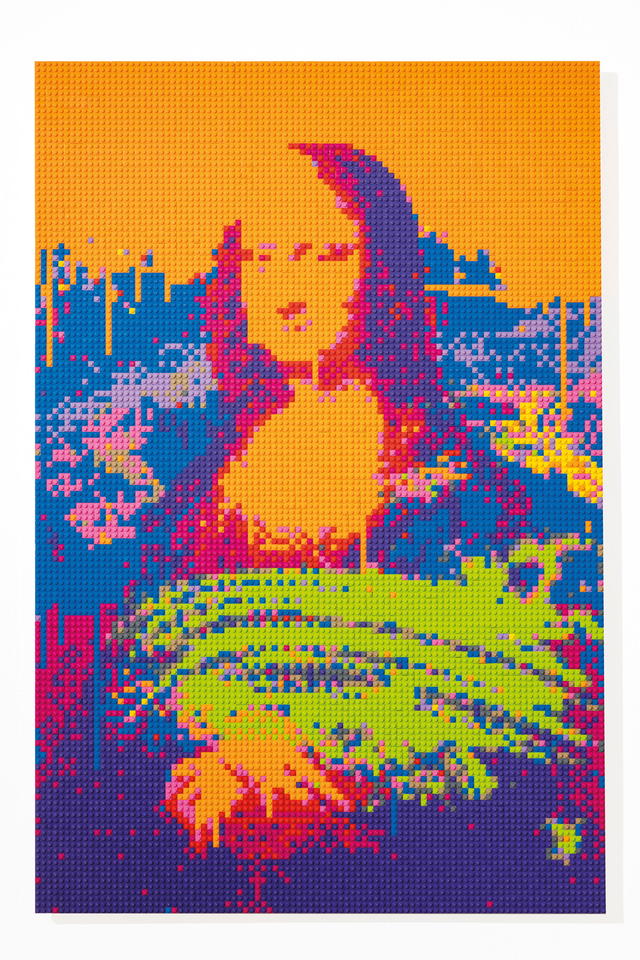

The locust invasion that destroyed entire crops in Pakistan in 2020 is superimposed over Vincent van Gogh’s ‘Le Semeur au Soleil Couchant’. Finally, Leonardo da Vinci’s ‘Mona Lisa’ is smeared with cake, recalling the vandalism perpetrated by environmentalists against the Louvre’s most prized possession.

Ai Weiwei's Interpretation Of The Mona Lisa

Photo: Ela Bialkowska OKNO Studio

Photo: Ela Bialkowska OKNO Studio

Photo: Ela Bialkowska OKNO Studio

Ai insists nothing is ever black or white. “My political position is never clear. The only right I am defending is freedom of speech, an essential human right. Humans have the right to express themselves. Freedom of speech also allows you to say something wrong or deemed wrong, so you can discuss it. If you don’t allow this kind of so-called wrongdoing, then you’re in a most dangerous society.”

He isn’t afraid to say the wrong thing. Neither Nor’s real show stealer is located above the stage in the gallery, which was formerly a cinema. This 6.84-m mural is inspired by da Vinci’s magnum opus, ‘The Last Supper’, regarded as the most important mural in the world. Using his own face instead of Judas’s, Ai has surreptitiously inserted himself into the iconic composition.

“A small amount of money led Judas to betray Jesus and put pressure on religion. Because of his betrayal, Jesus became Jesus. A story needs someone like Judas, in my opinion. So I put myself in the role of Judas because I want to tell people not to trust me. Since young, I’ve been full of bad ideas, and I’ve been able to put them into action. I’m the type of person who makes trouble smartly, and art is all about making trouble,” he concludes.

As I leave him, I do not doubt that Ai will continue his ways that awaken humanity’s social conscience wherever his art leads him.