The evening rush hour in Samarkand is in full swing, and I can hear the faint din of traffic in the distance from my vantage point at Registan Square. I am standing in the centre of this open plaza flanked by three ornate madrasahs that were once important schools for both religious and secular education in the region.

However, my mind isn’t on the dazzling blue tiles that adorn these monuments, or the flickering lights that slowly illuminate them. What I am thinking about is how all roads in Samarkand still lead to this plaza, as they did many centuries ago. Just for different reasons, though.

The Registan, literally meaning sand or desert, was once a gathering place for town folks to listen to royal proclamations, celebrate festivals, and watch public executions. The markets lining the square were where traders and merchants from all over the world gathered to haggle over an unimaginable variety of goods. Back then, rush hour must have meant something entirely different.

As you might have guessed, I am in Uzbekistan, the landlocked central Asian country that was once an important stop on the Silk Road, an extensive network of trade routes. From silks and spices to algebra and oriental philosophy, all kinds of things passed through these roads and bazaars between China and Europe.

For over 1,500 years, from the 2nd century BC to the mid-1400s, endless throngs of caravans plied this trade channel, picking up and passing on thoughts and ideas along with disposable goods, precious metals, and fine textiles.

Thanks to its strategic location right in the middle of this passage, Uzbekistan managed to imbibe the best of cultural mores, cuisine and crafts from various sources, including China, Mongolia, India, Iran and Turkey.

More recently, Uzbekistan was part of the erstwhile USSR, from 1924 until it declared independence in 1991. Reminders of this cultural conflation are all around, with the past and the present existing side by side. I quickly learn to say thank you in both Uzbek (“rahmat”) and Russian (“spasiba”), and discover both soupy dumplings from the east and the Persian samsa (savoury meat or potato pies) traditionally cooked in a tandyr, which is much like the tandoor.

On this current Silk Road exploration journey, I have flown into the capital city of Tashkent and taken a train to Samarkand, just two hours away. In its world heritage site inscription, UNESCO says, “The historic town of Samarkand is a crossroad and melting pot of the world’s cultures”.

Founded around the 7th century BC, Samarkand at its peak was one of the most important sojourns on the Silk Road. Even after the land trading routes were closed, the rulers of the Timurid dynasty—successors of the Turco-Mongol conqueror Timur—continued to keep Samarkand flourishing as a centre of trade and education by building monuments like the ones I am currently staring at.

In Uzbekistan, there is no escaping Timur, also known Amir Timur or Tamerlane by the rest of the world. Particularly in his capital Samarkand, where his legacy lives on in many ways, including this trio of madrasahs built by his successors. As with most of Uzbekistan’s historic sites, they have also been painstakingly—and somewhat controversially—restored in recent decades, and now shine with renewed vigour.

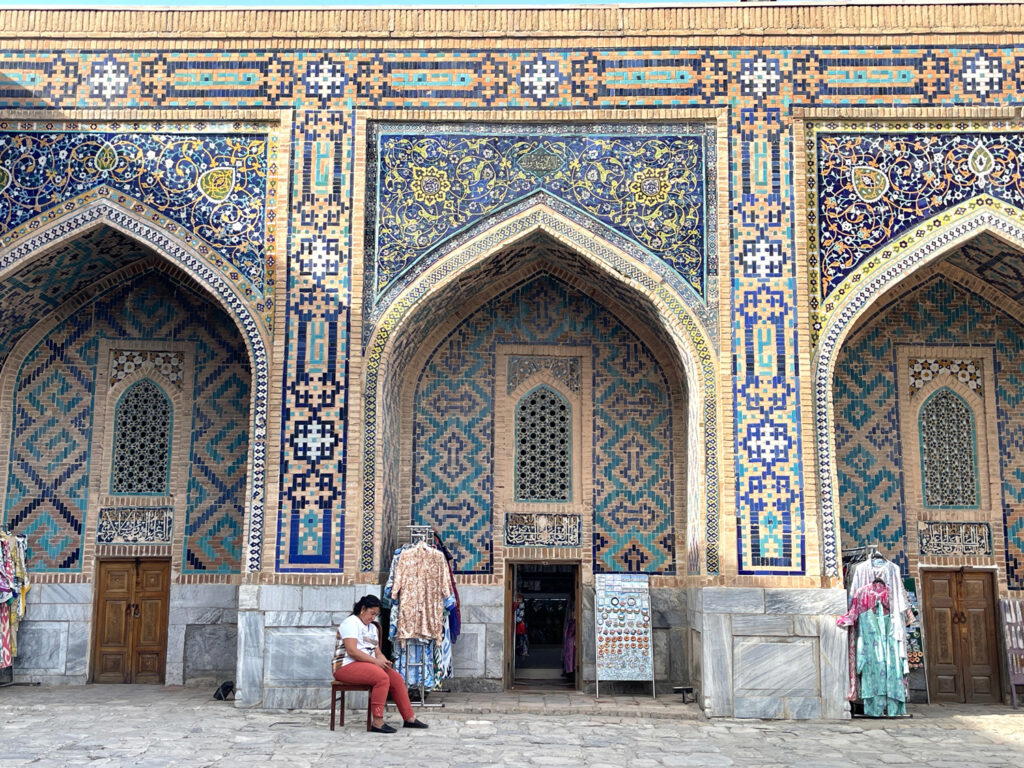

These madrasahs, built between 1420 and 1660, may not have the crowd of eager scholars now, but Registan is still pulsing with the excited clamour of tourists and the persuasive sales pitch of craftsmen and souvenir sellers who have set up shop within their inner courtyards. But even the finest tapestries at these ateliers fail to awe and impress as much as the profusion of glazed mosaics in a dozen shades of blue decorating the minarets and cupolas.

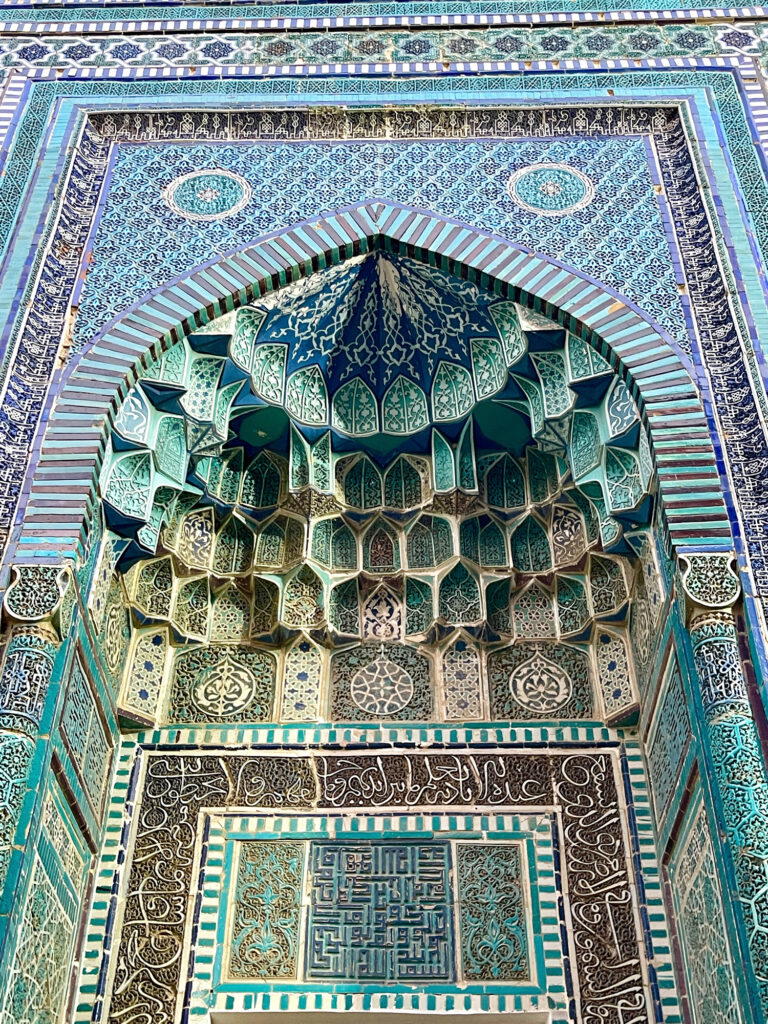

The next morning, my first stop is Shahi-zinda, which eventually turns out to be my favourite site in all of Uzbekistan. This is strange, considering that Shahi-zinda is a necropolis, a collection of mausoleums neatly lined up on top of a squat hill in the heart of town. But when I enter, the early morning sunlight is playing magic with the cobalt and aquamarine tiles, turning them into molten gold. I am immediately and irrevocably enchanted by this remarkable monument, where many of Timur’s relatives are buried.

From there, I head to Gur-e-Amir, where the mighty man himself is entombed in a suitably impressive central room with sumptuous gold-toned walls and ceilings.

There is a lot more to see and do in Samarkand. After all, this city has attracted the attention and praise of travellers from all over the world, from Alexander the Great when he visited it in 329 BC to Ibn Batutta, who called it “one of the greatest and finest of cities, and most perfect of them in beauty”.

But it is time to move on to Bukhara, the other great city that flourished as a hub of both culture and commerce. Countless attractions and covered bazaars lie scattered through the compact heart of the city known as the Historic Centre, another of Uzbekistan’s UNESCO world heritage sites.

Most of this area is pedestrian only, with tour buses dropping off groups at a distance and e-rickshaws ferrying tourists too tired to walk. I am staying in a boutique hotel in one of the cobblestoned main streets of this neighbourhood, within convenient walking distance of the major sights.

After the busy city vibes of Samarkand, Bukhara feels quieter and more laid-back, and it is easy to see why many visitors count this as their favourite town. The individual landmarks are dazzling in their own way—the Poi-Kalyan complex of mosque, madrasah and minaret; the 5th-century stone citadel known as the Ark; the Bolo Hauz mosque; the tiny Ismail Samani mausoleum. But what I find most charming about Bukhara is the open friendliness of the locals.

Tired from all the monument hopping, I stop at the Kolkhoznyy Rynok (Central Market)—not because I am in the mood for shopping, but because I am drawn to the array of ruby red pomegranates and succulent slices of melon on display. This Soviet-era market is bustling with local shoppers, but the vendors still find the time and patience to hand out samples of their hard cheeses and candied fruit.

“No need to buy, just try this—our special Uzbek bread,” says a young girl, as she breaks off a generous piece of the flatbread known as lepeshka. From another aisle, a couple beckons to me with a handful of walnuts and pistachios, smiling insistently as I try to refuse. The cheese lady wants me to take a selfie with her, and before I know it, a bunch of other head-scarfed vendors photobomb us enthusiastically.

Having ventured in without intending to buy anything, I walk out with several bags of goodies to take home for myself and as gifts.

On my way back to the hotel, I stop at the trading domes for a feel of what shopping in Bukhara during earlier times must have been like. These covered markets were each located at a crossroad, and used to specialise in a single item—jewellery, caps and turbans, books, carpets, and so on. Only four remain now, selling modern-day souvenirs ranging from textiles and carpets to musical instruments and embroidered shawls in an atmospheric medieval setting.

Walking through these bazaars is also a reminder of Bukhara’s reputation for fine arts and crafts. Even now, there are innumerable workshops and studios tucked into every nook and corner, showcasing traditional suzani embroidery, metalwork, calligraphy, miniature painting, and carpet weaving.

Having seen the places where outsiders typically go in Bukhara, I later take an evening stroll to where locals congregate. The Lyabi Hauz complex, with its rectangular pond on one end and the Nadir Divan-Begi Madrasah on the other, is an open green space that now seems like any other modern city park. Several families have gathered around cups of fragrant tea at their favourite chayxonas (teahouses), their raucous laughter floating in the cool evening air. This is a rare glimpse into daily life in this country, where I am constantly delighted by how the old rubs shoulders with the new.

Dinner over, I walk back all the way to the Poi-Kalyan complex to see the imposing Kalan minaret lit up. This may be one of the rare monuments in this region unadorned by glossy majolica tiles, but it was magnificent enough to stop Genghis Khan in his tracks.

According to local legend, the marauding Mongol razed everything in his path, but spared this early 12th-century tower—whether out of admiration or apathy, I am not sure, since various tourist guides have their own version of what may have happened. But I can see the appeal of this starkly majestic tower.

The next day, a long drive past brown, barren lands takes me to the town of Khiva, on the very edge of the Kyzylkum Desert. My destination is the UNESCO-listed Ichan Kala, the old walled city with dozens of landmarks lining its narrow lanes. As the sun is just about to set, I walk up the steep steps of the watchtower at the Kuhna Ark that once served as the ruling khan’s residence and fortress just in time to see the desert sky turn a flaming orange and then a pale pink before cloaking all of Ichan Kala in darkness. Standing there, I watch as the lights are turned on, bringing the minarets and madrasahs into sharp focus.

Samarkand and Bukhara have allowed me to explore on my own terms, stopping where I wished to observe contemporary life in this country. In Khiva, however, all the attractions are contained within the walls of the Ichan Kala, which has been preserved as a living museum. I begin at the squat, unfinished tower of Kalta Minor, with its stunning decoration of tiles in teal and turquoise, several shades lighter than the blues of the towns I have seen so far. Then there are the palaces within Kuhna Ark, the various madrasahs and finally, the Tosh Havli Palace, with its splendid harem containing the most lavish tilework of them all.

Once I have had my fill of the landmarks, I walk up and down aimlessly, peeping into carpet-weaving workshops and wood carving studios, stopping for Uzbek lemon tea at one of the al fresco choyxanas.

I end up chatting with souvenir salesmen who ask me where I am from. “Hindostan!” they exclaim in delight when I respond, using the old name for India. “Shah Rukh Khan!” they add for good measure. They seem as enchanted by the glitz and glamour of Bollywood movies from my country as I am by the beauty and grandeur of the ancient monuments in theirs.

Khiva is where I have the most powerful spiritual experience of this trip, finding my breath slowing down at the sparse Juma Mosque’s open prayer hall. This sense of peace follows me to the memorial of Khiva’s revered poet and philosopher (and strangely enough, also a fierce wrestler) Pahlavon Mahmud.

As I admire the brilliant tiles covering every inch of the walls and ceiling at what has become a holy pilgrimage site, I hear a man’s voice rise up in prayer, cutting through my contemplative silence. Tourists all around me pause their low-pitched conversations and respectfully turn towards him. I don’t follow the faith or understand the words, but the sonorous worship is comforting and appropriate.

As I planned my trip to Uzbekistan, I had no idea what to expect beyond its blue-tiled monuments. I arrived to discover a land with multiple layers of history, intermingling cultures, and constant reminders of its melting pot ethos. More importantly, the people are friendly and go the extra mile to make me feel at home. One day, your road should lead here as well.