The sea lay glassy and still, a silence so deep that it felt almost sacred, until a sudden plume of spray shattered it. A pod of humpback whales rose before us, their dark backs arching gracefully through the water.

We leaned over the railings, mesmerised as their tails lifted high and crashed down with a deafening slap that sent ripples racing across the fjord. Misty spouts of mist, sun glinting on wet flukes, and the echo of deep calls echoing through the Arctic air held us spellbound.

Then shadows glided just beneath the surface before breaking fully into view. Fin whales, the second-largest whales on Earth, moved with quiet majesty, their massive bodies dwarfing humpbacks. Greenland hosts 15 whale species, from minke and humpback to beluga and narwhal.

The calls of fin whales, however, span hundreds of kilometres and they swim with their mouths open to catch and filter prey, our expedition team explained. There was grace in every motion, as if the ocean bowed to their rhythm. Some cameras clicked, but most of us stood in stunned silence, grateful to witness one of the ocean’s most humbling spectacles.

I was aboard the expedition ship Ocean Albatros run by Albatros Expeditions (or, since mid-October, Polar Latitudes Expeditions post-merger), sailing along the wild, jagged coast of Greenland, Denmark’s autonomous territory and the world’s largest island, on an 11-day journey.

We had flown in on a chartered plane from Copenhagen, landing at Kangerlussuaq in West Greenland, a former US air base during World War II. Beyond the airstrip, the edge of the Greenland Ice Sheet stretched: vast, white, and seemingly without end.

Our first excursion was a drive to Reindeer Glacier in tundra trucks, past frozen ground dotted with red wildflowers and lichen, a hybrid colony of algae. Besides woolly musk oxen, which can weigh as much as 400kg and are named after a strong scent released by males during mating season, we also spotted reindeer grazing.

This was Greenland’s heart: immense, silent, and slowly shifting due to climate change. From there, we visited Aasivissuit, a Unesco site and summer hunting ground for the Inuits. Living hunting traditions coexist with archaeological traces of settlements. As our guide explained, winter settlers hunted caribou and dried its meat alongside trout, seal, and whale for the long Arctic winter.

After boarding black inflatable Zodiac boats from a small jetty, we reached the Ocean Albatros and its luxurious, spacious cabins with balconies, lecture and observation lounges, along with a library, jacuzzi, sauna, and gym.

The voyage began with introductions to the crew and expedition team. Then we donned muck boots, strapped on life jackets, and once again stepped into bobbing Zodiacs. We glided past glaciers whose ice shimmered in shades of blue. Scientists aboard the boats warned that glaciers were receding here, reshaping ecosystems and fjords.

We also learnt that roads are rare in Greenland because of its rugged terrain, where fjords carve the land and ice covers it. Most people get around in dog-driven sleds, snowmobiles, and boats.

It was fascinating to visit tiny settlements like Kangaamiut and Aappilattoq, clinging onto fjords and formidable rock faces. With upturned boats and sleds in their yards, wooden homes with bright colours and sloping roofs lined the rough terrain. There was a school, a grocery store, a church, and a soccer field in every small settlement, whose residents welcomed us with soulful choir music and kaffemik, the traditional sharing of coffee and cake. Almost everyone makes a living by hunting or fishing.

Life On The Ice

Most young people, however, move to Nuuk after high school. Lying further south and stretching along the coast, Greenland’s capital has about 20,000 people. Founded by the Danes in 1721, it blends modern life with traditional Inuit customs. Colourful murals brighten its harbour and the shoreline is lined with statues honouring the “Mother of the Sea”, the Inuit goddess who controls all sea creatures and the bounty of the ocean.

In the Greenland National Museum and Archives, mummies preserved in permafrost and ancient wooden kayaks offer glimpses into a history shaped by the sea, ice, and human invention. Kayaks, once crafted from driftwood and sealskin, were fitted precisely to their owners’ bodies, a perfect marriage of craft and survival.

Without a doubt, the West Coast felt connected, green, and navigable, yet still wild. Glaciers calved dramatically, fjords were navigable, and towns such as Nuuk bridged tradition and modernity.

Following this, we sailed to Qassiarsuk in South Greenland, billed as the “Garden of Greenland”, where Norse settlers farmed fertile valleys. There were reconstructed turf houses beside meadows where fluffy sheep grazed. A short journey led us to Igaliku, where the ruins of 12th-century Gardar, the residence of bishops, spoke of Norse farmers living alongside glaciers and fjords. Now, those same glaciers were retreating, reshaping the land.

Leaving the accessible west, the ship turned east through Prince Christian Sound, a 100-km corridor of jagged cliffs, icebergs, hanging glaciers, and lofty peaks soaring as high as 2,200m. We were told that Greenland has some of the oldest rocks on earth—up to 3.8 billion years old—due to a lack of recent tectonic movements. It was a place of silence, only broken by the occasional roar of the calving ice. Indeed, the untamed nature of East Greenland makes humans feel small.

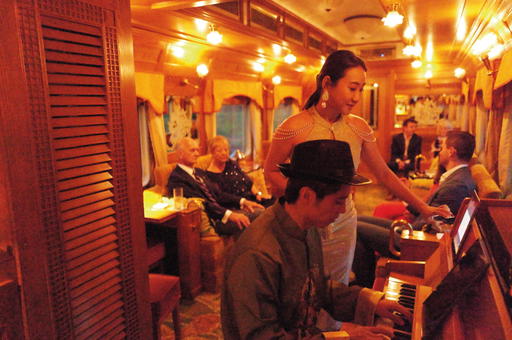

Life aboard the Ocean Albatros quickly found its own rhythm again. Mornings began with quiet moments in the sauna and gazing out at drifting ice, while afternoons were often spent on deck alongside expedition leaders, scanning the horizon for wildlife.

Between landings, guests gathered for lectures that ranged from geology and marine biology to an engaging introduction to the Greenlandic language. Conversations flowed easily, too, whether with the crew, representing more than 29 nationalities, or with fellow travellers from across the globe. Each encounter added a new perspective, turning the voyage into as much a cultural exchange as an Arctic adventure.

DRAMATIC SCENERY & ICEBERG HIGHWAY

We also hiked through Queen Marie Valley, feeling like pioneers in the wilderness, where glaciers fed a rushing stream beneath towering, jagged peaks. Our path crossed permafrost and spongy ground, thick with crowberries and wildflowers in vibrant yellow and red shades. Also, since this was polar bear territory, our expedition guide had a rifle.

Then, sailing into the vast expanse of Sermilik Fjord, its waters nourished by three mighty glaciers, we found ourselves surrounded by some of Greenland’s most dramatic scenery. Jagged mountain ranges rose like sentinels on either side, while great rivers of ice spilled into the fjord, calving into an endless procession of icebergs.

In our Zodiacs, we drifted through what an expedition leader called “iceberg highway”—a shimmering corridor of ice giants, some taller than city buildings; others sculpted into fantastic shapes and shaded in whites, aquas, and deep translucent blues.

Laura, one of our guides, explained that some of these icebergs were formed millennia ago. In their striated patterns, glaciers grind across rock, gather debris, and compress under immense weight. The deeper the compression, the more the ice transformed, creating those rare, luminous blue tones that glow from within. I was reminded that every iceberg was more than a spectacle; they were stories embedded in ice and time.

At Ikateq’s Bluie East Two, the past lingered in rust and silence. As a former US airfield during World War II, it is now littered with corroding barrels, weathered trucks, and the skeletal remains of machinery slowly surrendering to time. Through this surreal landscape, wildflowers and tundra vegetation have begun to reclaim the ground, leading us to a glassy glacial lake. Nature weaved itself around war relics, creating a haunting contrast. Our minds were left wondering, should such a place should be cleared away or should its existence as an open-air monument be preserved?

Finally, we reached Tasiilaq, the largest town in East Greenland. Brightly painted houses clung to hillsides, with cod fish hanging out like laundry, and steep staircases connecting them to the streets. Children ran through the streets as sled dogs barked in chorus. In Flower Valley, beyond the town, Arctic blooms exploded.

Greenland’s vastness seeped into our bones. Time felt suspended here, measured not by clocks but by the slow pulse of ice and the rhythm of the tides. Somehow, we felt at once infinitesimally small and intimately connected to this fragile, immense landscape. A fjord’s curve, a shimmering fluke, or a retreating glacier reminded us that this was a place alive with motion, memory, and resilience. Witnessing it, even for a moment, was humbling.