In the gardens of L’Hôtel de Maisons during last October’s Design Miami Paris fair, Vikram Goyal’s installation ‘The Soul Garden’ unfolded like a quiet apparition. Five sculptural creatures—an elephant and its baby, a tiger, a tortoise, and a crocodile—rose from the manicured lawns in rippling contours of hand-worked brass.

The area was also filled with olfactory molecules created with Sissel Tolaas, a Norwegian artist and researcher known for her work with smell, who was inspired by the ancient Indian mythology of the Panchatantran.

These olfactory layers were created with Vikram to entice visitors into his interpretation of the ancient Indian collection of interrelated animal fables. “It’s a sensory space where craft, mythology, and scent come together to invite reflection and connection with nature,” he says.

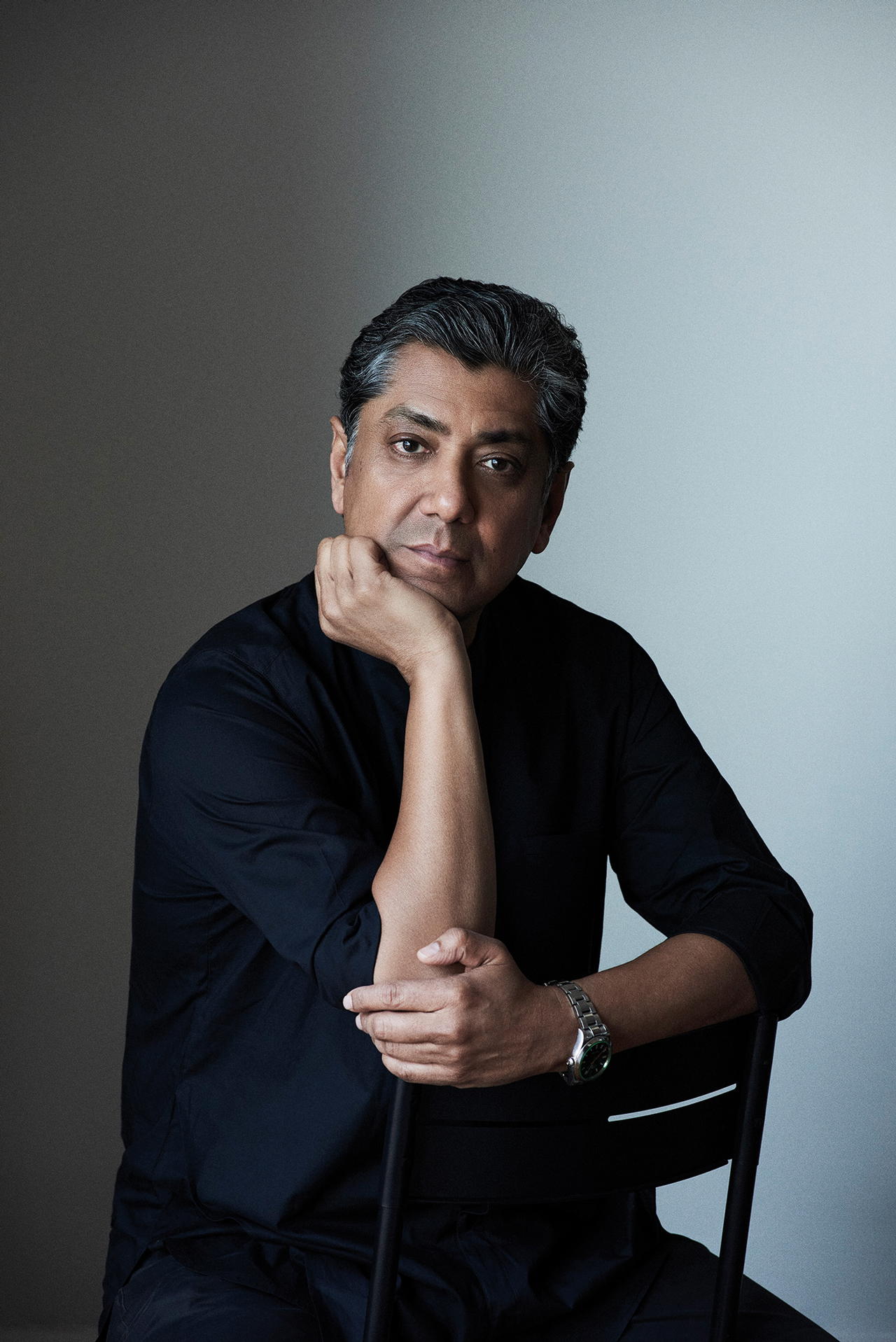

At the heart of his practice is a commitment to designing objects that feel alive, rooted, and resonant. Despite being one of India’s most internationally recognised designers, his path to collectible design was anything but straight. He was born in Jaipur in 1965 and raised in New Delhi, but spent most of his childhood in Rajasthan, where his mother’s family lived. Those early years left a lasting imprint on him that he still considers foundational.

His memories include palaces, carvings, painted walls, and a physical presence of art, ornament, and history. “In my work, that landscape remains a silent collaborator, which channels scale, surface, and memory.”

His parents nurtured intellectual rigour and instinctive respect for cultural heritage. These dual sensibilities shaped how he saw the world and led him to pursue engineering at Birla Institute of Technology And Science – Pilani in India and later a Master’s degree in development economics at Princeton University. From there, his path seemed conventional: a promising finance career at Morgan Stanley in New York and Hong Kong.

PRECIOUS METAL

However, something was missing. Although rewarding, the corporate world left him yearning for something “more rooted, material, and expressive”. It brought him back to India in 2000 and to a master craftsman named Ramesh, brass sheets, hammers, and the beginnings of a studio that redefined Indian metalwork possibilities. “This transition was deeply personal rather than opportunistic, a pull from inside me towards material culture,” he notes.

Brass is Vikram’s signature medium today. “Metal, especially brass, has an alchemical quality,” he says. “It responds to the hand, carries weight and presence, and ages gracefully. In India, brass has deep cultural resonance, from ritual vessels and temple ornaments to everyday objects.”

In his hands, the age-old repousse technique becomes expansive and sculptural. “Repousse is the beating heart of our studio,” he discloses. “You hammer from the reverse side; you don’t see the result until it’s nearly finished, which means there is an element of discovery and risk.”

His atelier’s invention of hollowed joinery, which fuses multiple hammered brass sheets together to create a hollow structure, allows monumental works to maintain a surprising elegance. He explains that its ethos is to push technique without sacrificing the handmade touch.