It was 1974. A lone, purposive expedition on foot through a dense jungle led Hannes Schmid to the indigenous Dani tribe of West Papua, Indonesia—cannibals he had read about in a gazette six months earlier. But he was persona non grata, so reception was more grotesque than gracious. The young Swiss photographer found himself pierced with arrows, pummelled and schlepped over rocks by his feet.

Back at the village, he was hurled into a pig sty. “I think they were shocked to see me,” he explains. He was let out for a lashing every two days and the tribe adhered to a strict hierarchy. “At the top were the warriors. Then the men. Then the boys. Then the pigs. Then the women. And then there was me!”

He gradually learnt their vernacular, estimating it comprises some 200 words. This enabled him to figure out why he was kept alive although despised: he was of no use to the tribe. Slaughter would have been ample effort for zero reward.

“The people believed that once they eat you, you would serve them in your next life. However, I was a wimp, always crying and begging. They had no interest in me being their servant,” he recounts with a roar of laughter. Emboldened by their disinterest, he hobbled off one day, by then emaciated and infected with dengue and malaria. His captors watched without batting an eyelid.

On his way down the mountain, he crossed paths with the Korowai, another cannibalistic tribe, but of South Papua. Curiously, the people were benevolent and nursed him, even agreeing to have their pictures taken. Soon, missionaries began hearing about about the white man living in a treehouse, so they arranged for a rescue mission. Schmid pinched himself when he was put on a flight back home.

South Africa, Singapore and the Orangutans of Sumatra

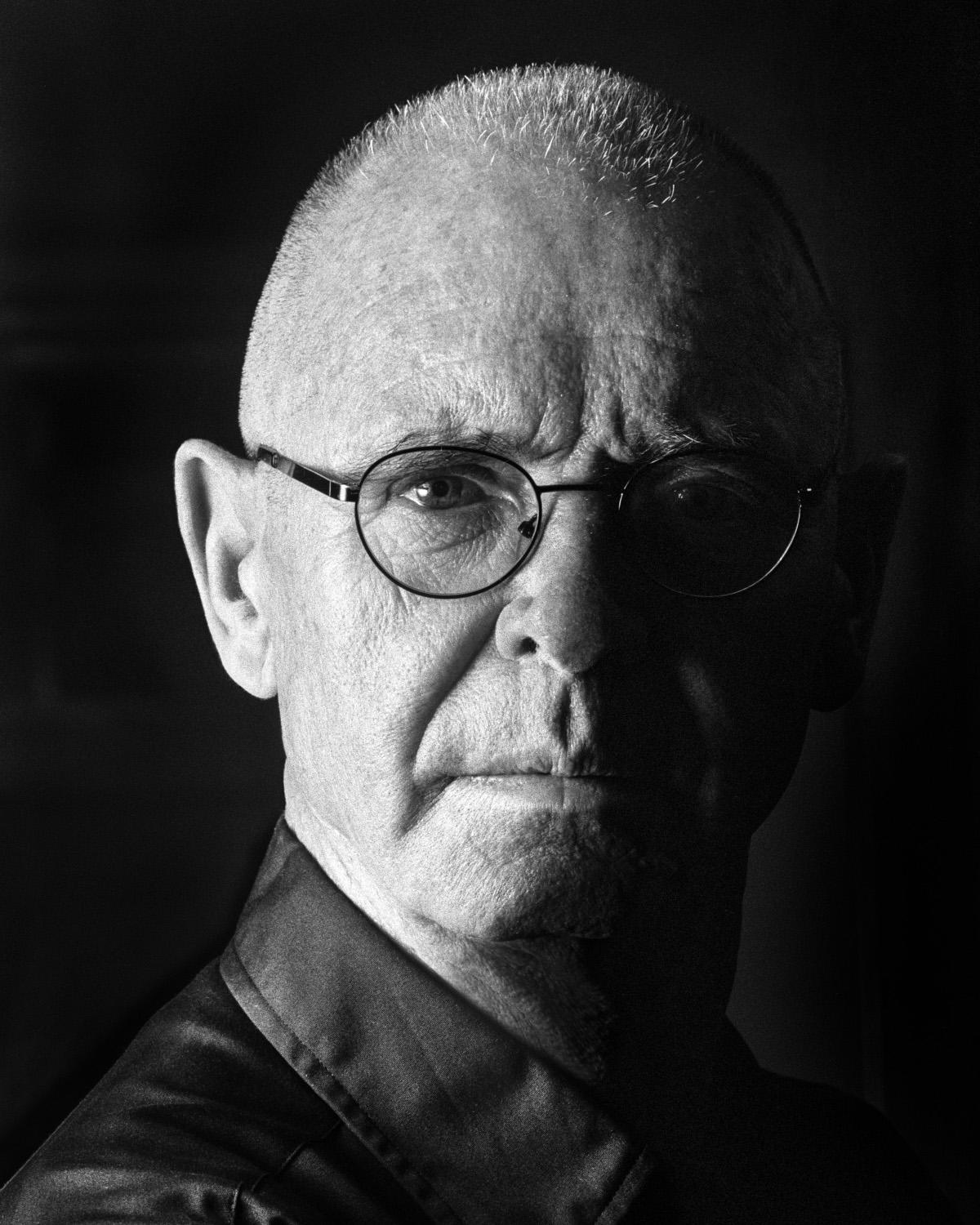

Born in 1946 to an impoverished family with four children, Schmid apprenticed as an electrician in his youth and moved to South Africa in search of work at the age of 22. With a secondhand Minolta 50mm, he picked up photography in a bid to share a glimpse of his travels with family, regularly mailing the films home.

It took him four years to discover that his photographs from his time in the country were largely inscrutable. “There were no print labs in South Africa, so I never saw a single picture,” he lets on. The first time I saw them was when I was back in Switzerland for a visit. I was so disappointed!”

When he was 26, he moved to Singapore for a job, but later decided he didn’t want to continue maintaining electrical systems. In the spirit of adventure, he relocated to Sumatra to work at an orangutan rehabilitation centre to work as an orangutan trainer. “The orangutans didn’t know how to make nests in trees, so I taught them,” he says. “Truthfully, I don’t know if they learnt from me or if I learnt from them. They were much better at surviving in the jungle than I was as a greenhorn.”

Schmid returned to Singapore a year later. While reading the local paper, he came across an article on Michael Rockefeller—the heir to the Standard Oil fortune was said to have been eaten by cannibals in South Papua in 1961. Instantly galvanised to locate the tribe, he booked the next flight out to Jakarta in the hopes of acquiring a special visa.

His request was denied, but the mad lad was undeterred and took up work as a chef on a Chinese ship. When the ship docked in Indonesia, he disembarked and started hiking with only a compass, two cameras, a suitcase of film and balls of steel. The rest is history.

Rock Stars, Supermodels and a Boat on a Mountain

Recovery from his ordeal in captivity took a year. When Schmid was back on his feet, a friend invited him to a concert by British rock band Status Quo. The unbridled headbanging promptly enthralled him. “They reminded me of the Dani people,” he enthuses. “On stage, everyone was shaking like crazy, as were the fans. I was like, ‘This is a tribe!’”

After the show, he was introduced to the band. Upon learning that Schmid was a photographer, the group told him to scram—as was typical of countercultural musicians of the ’70s, the band loathed the press. But they were urged to give him a chance.

“My friend said, ‘No, no, he is a crazy guy! He has eaten rats and beetles. He has photographed cannibals.’ He told me to share my story, so I did.”

Hannes Schmid on the incident that led to his career in rock photography

Intrigued by his temerity, the band manager invited Schmid to do a photo session with the band the next day. Status Quo not only ended up loving the pictures, but also the ardour of the man they saw as a respectable screwball. Schmid scored a job as a tour photographer on the spot.

At the end of eight years, he had photographed 257 of the most celebrated bands of the mid-’70s and the early ’80s including ABBA, The Rolling Stones, Genesis, AC/DC, and Motörhead. Music industry honchos banging on his door meant a German fashion magazine eventually got in line.

“They asked: ‘Can you do fashion photography?’ I said, ‘I can’t. I only take pictures of rock stars’,” he says. The publication engaged him anyway and the images were a hit—there was just something different about this photographer’s intrepid streak. Overnight, he went from rock photographer to fashion photographer, inundated with shoot requests from high fashion magazines and brands around the world. “Kenzo saw my work and invited me to Paris. Then Italian Vogue called. Then American Vogue, Gucci, and Prada. I became one of the most sought-after fashion photographers at that time.”

Schmid had a knack for creating sets that were larger-than-life, positioning models from Mount Everest to the front of the North Face of the Eiger. Till this day, a boat is stuck somewhere up in the mountains because the crew was unable to haul it back down after a shoot. It is a little secret he lets on with a chuckle.

“Giorgio Armani once told me, ‘You know Hannes, it’s a bit crazy. We send you off and we never know what we’re gonna get. But it’s always good,’” he lets on. “I replied, ‘Well that’s important to me.”

Not a Camera, but a Paintbrush

Music and fashion photography was trailed by work in advertising—billboard giants also wanted a piece of him. Schmid moved on to photographing Marlboro campaigns for a decade, playing an instrumental role in recreating the cigarette ads of the Marlboro Man. The fictitious character was a cultural marker of the 90s as American masculinity was epitomised by the archetypal rancher who smoked while riding into the sunset.

Ironically, Schmid has never been a smoker, so colleagues were never allowed to puff away on set. “I always wore a badge that said, ‘Thank you for not smoking’ at work,” he chortles. “This was a bit of a problem, but they had no choice. They needed me!”

In 2001, he discovered that his iconic cowboy photographs were appropriated by Richard Prince, a notorious prankster in the art world. Unable to take Prince to court because of fair use—a doctrine in US law that permits limited use of copyrighted material without obtaining permission in advance—he deliberated over the best way to reclaim his work.

The brilliant mad man’s solution? To also appropriate his own pictures. “See, a photograph is already a reproduction of art. The original is the film negative,” he explains. “By using my picture, Richard Prince was making a reproduction of my reproduction. I decided to appropriate my own photograph in another medium to stand up to him.”

It was 2005 when Schmid set down his camera to pick up a paintbrush. His first few paintings, he stresses, were horrifying. “Painting a horse is challenging enough. Painting a human on a horse was beyond my ability.”

But his indomitable nature saw the hyperrealistic oil-on-linen paintings develop quickly. The next step was to have them assessed and exhibited, so he packed the scrolls in a ski bag, flew to New York and turned up at the Gagosian. The contemporary art gallery exhibits some of the most influential artists of the 20th and 21st centuries in various gallery spaces around the world.

At the gallery’s office, he found himself rebuffed—he just was not worth their time. “A staffer said, ‘Sir, we are the Gagosian. We do not seek out artists. The world’s best artists seek us out,’” he says. “I replied, ‘Can you imagine if I were the next artist of the century and you missed out on this opportunity? Will your boss be happy?’”

The paintings were surveyed. In 2008, they were put on show and caught the attention of the global press, so art experts came by to scrutinise his techniques. “I had no techniques! I learnt painting on my own,” cackles Schmid. The pieces also earned him a couple of awards.

Save the Cambodian Children

Adventurer. Photographer. Painter. All-around brilliant madman. Now, Schmid is a humanitarian. As with most of his big breaks, welfare work came to him through a chance encounter. While walking on the streets of Thailand in 2013, he stumbled upon an adolescent acid burn victim begging for money. The girl was Cambodian and had been sold by her father to a crime syndicate. Beaten, abused and mutilated, she had never been inside a school or a doctor’s office.

“I was shocked. We see them in the news and in movies, but when you stand in front of a child so terribly destroyed, shivers go right down your spine.”

Hannes Schmid on the encounter that catalysed his endeavour to help exploited Cambodian children

Schmid bundled her into his car and drove her across the border to an orphanage in Phnom Penh, where he learnt that some 300 children in the area are disfigured by gangs every year. Most of them live on a dumpsite. “I thought, ‘Why doesn’t the world know this? What happened here?’ ” he says. “I was by then almost 70 years old. But after years of supermodels, big brands and five-star hotels, I thought maybe there was more to my life.”

He rounded up 280 children and registered them at school, also buying 280 sets of uniforms, pairs of shoes, and backpacks. Knowing that there was a need for a sustainable way of funding them, he gathered together the families of the children in the slums and transported them to farmland. An agricultural village was set up to help them become self-sufficient.

In 2014, he co-founded Smiling Gecko. A non-governmental organisation based in Kampong Chhnang, Cambodia, it has undergone several challenges—vegetables not growing, chickens not laying eggs, fish swimming upside down, and pigs perishing—but Schmid has stayed the course. “The farm failed three times. However, my philosophy is that if you fail and fail again, eventually you fail better.”

Today, Smiling Gecko Cambodia is a thriving community and the site has expanded from nine to 150 hectares, impacting approximately 30,000 nearby residents. On top of providing 466 children with an education, it offers adults vocational training and job opportunities. Board committees include Adrian Dudle, chief compliance officer at Zuhlke Engineering; and lawyer Ines Poeschel; all of whom contribute their skills and knowledge freely, even covering their own expenses. “I would say without arrogance that we currently have the best school in the country,” asserts Schmid.

Some 90 locals are employed at Farmhouse Resort and Spa, a sustainable luxury holiday resort managed by Smiling Gecko Cambodia and an hour’s drive north of Phnom Penh. Situated next to the campus, the award-winning hideaway directs all revenue to finance education and other humanitarian initiatives by the organisation. In recognition of his efforts, Schmid was awarded an honorary doctorate by the University of Zurich in 2018. He regularly speaks at various events on transformation and human capital.

At 77, Schmid may no longer be navigating a jungle, but he is still embarking on a journey. He currently devotes all his efforts to developing the Farmhouse Resort and Spa and finding new ways to support underprivileged Cambodian children.

“Why do children in other countries have the right to clean water, medical attention, and education, but not them? Education is also a human right recognised by UNESCO,” he reasons. “The problem is that we have never defined what education is. What drives me is inequality. It is what I’m fighting for.”