When you go back far enough in human history, the world map narrows down to a single continent. The earliest Homo sapiens fossils point to Africa as our original homeland. This is where rivers, forests, and savannahs predated our species by millions of years. In the minds of many biologists, that extraordinary biodiversity is more than just a backdrop to our origins. We are who we are today because of it.

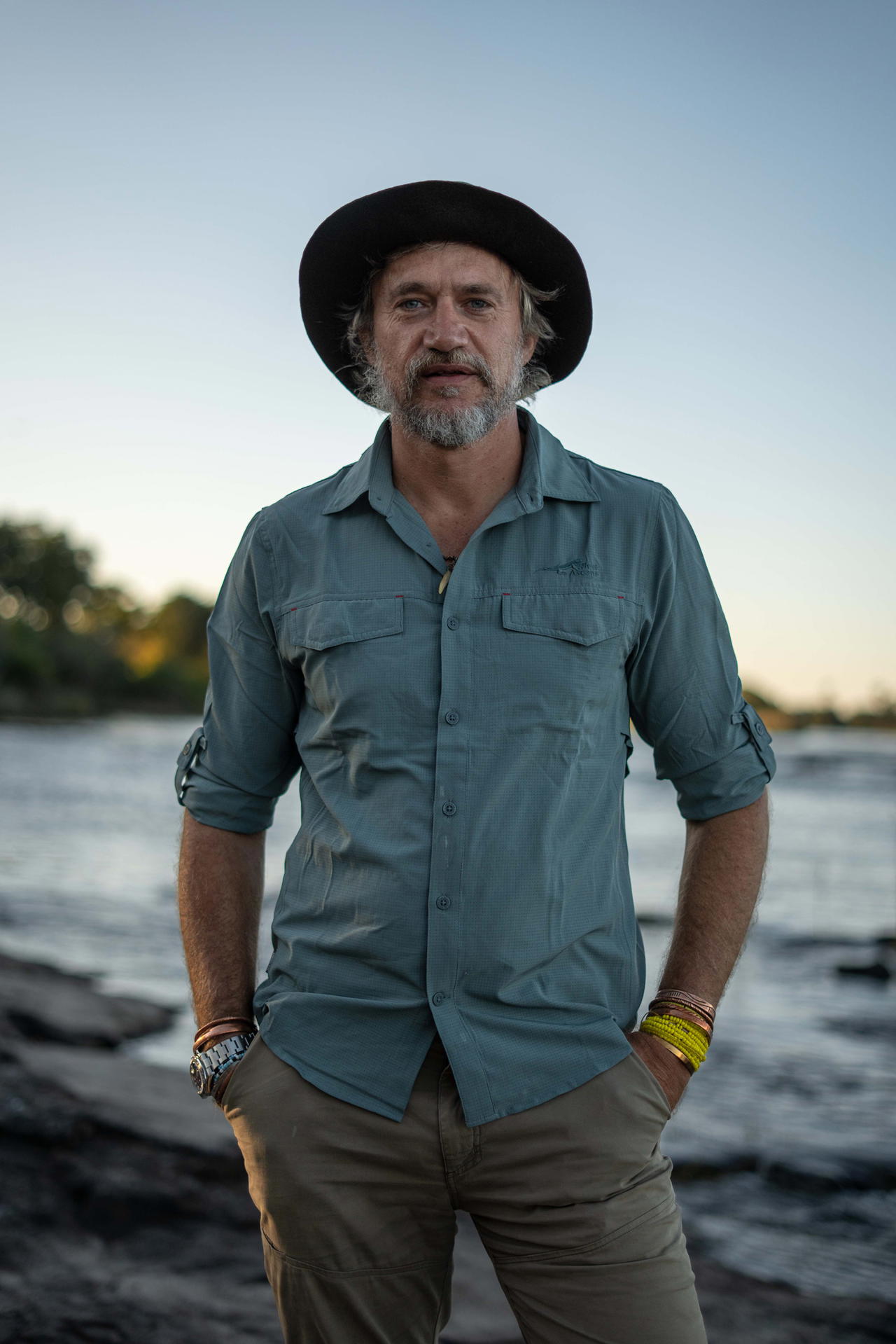

There are few people who take that idea as personally as Steve Boyes. The ornithologist, conservation biologist, and chairman of the Wild Bird Trust has spent over a decade exploring remote wetlands, mapping uncharted watersheds, and documenting species at risk of extinction.

As a National Geographic Explorer, Senior TED Fellow and Rolex Perpetual Planet Initiative partner, he has dedicated his life to conserving the fragile ecosystems that sustained early human societies and continue to sustain millions of Africans today.

Rolex’s partnership proved crucial. In 2019, the Perpetual Planet Initiative, which supports scientists and explorers working in the frontlines of climate change, enabled Boyes to expand a series of isolated expeditions into something much more ambitious: a coordinated scientific programme aimed at studying and protecting the highland water towers that feed Africa’s great rivers.

Through that support, he also founded the Wilderness Project and launched the Great Spine of Africa expeditions in 2022. The inaugural Lungwevungu Expedition in the Lisima Lya Mwono landscape of the Angolan Highlands followed a tributary long believed by local communities to be the true source of the Zambezi.

For weeks, Boyes and deputy expedition leader Kerllen Costa travelled in dugout canoes, navigating rapids and crocodile-infested channels while gathering data that ultimately confirmed the communities’ intuition.

“The Lisima Lya Mwono (‘Source of Life’) landscape is a system of source lakes and previously undocumented peatlands—the second largest peatland discovery in tropical Africa. I found it astonishing that this was not globally recognised.”

Steve Boyes, Rolex Perpetual Planet Initiative partner and Founder of the Great Spine Of Africa Expeditions

Last year, his work converged on a single moment at the 2025 Ramsar Convention in Zimbabwe—the world’s most important forum for protecting wetlands. Standing beside the roaring Victoria Falls, Boyes delivered a 15-minute address that distilled years of fieldwork into one urgent call: to secure international protection for Lisima Lya Mwono.

His case rested on new science. Boyes and his colleagues published a peer-reviewed study last year, combining expedition data with high-resolution satellite imagery that strongly suggests that the true source of the Zambezi River lies in the Angolan Highlands.

Lisima Lya Mwono, which means “source of life” in the local Luchaze language, represents a network of source lakes and vast expanses of previously undocumented peatlands. A natural water tower for millions downstream, it is the second largest discovery of its kind in tropical Africa.

However, science alone wasn’t enough. Before taking to the stage, Boyes sought the counsel of the river’s traditional custodians—kings and chiefs from communities along the Zambezi—who had gathered to hear the findings and lend their support; some for the first time in 60 years.

“This meant a huge amount to me. Rivers unite people across borders. They are river guardians, and are proud of the water. It is an agreement across five countries for us to work very closely with them to monitor the ecosystems,” he told the audience.

With backing from these leaders and key regional collaborators, including Ramsar secretary-general Musonda Mumba and Nyambe Nyambe of the Kavango Zambezi Transfrontier Conservation Area, Boyes and his team believe Lisima Lya Mwono could be designated a Ramsar Site within months.

Such a listing would bring national and international protection, with policies centred on sustainable land use for communities that depend on it. Lisima Lya Mwono is only one chapter of a much greater effort. Since launching the Great Spine of Africa expeditions, Boyes and his team have been working to map and monitor the continent’s most critical highland water systems, which also include the sources of the Congo and Nile Rivers.

The Wilderness Project has also completed 20 expeditions in a single year, with plans to reach 25 this year as the team moves deeper into the Congo and Nile basins. The ultimate aim is to safeguard 1.2 million sq km of watersheds, plateaus, and rivers by 2035.

Physically, work is punishing. Boyes spends nine months a year away from home, paddling up to eight hours a day. In addition to being capsized by hippos, charged by elephants, and hospitalised for malaria, he is also a cancer survivor. But the stakes, he argues, dwarf the risks.

If protected, the 15 million hectares identified as the Zambezi’s source would constitute the third largest Ramsar Site in Africa and one of the largest in the world. It would also be a vital buffer for over 20 million people, countless species, and hundreds of millions more downstream.

“Only 14 percent of Africa is protected today. Whenever I go to the source of a river, I see communities already caring for it. They just need to be recognised,” says Boyes.