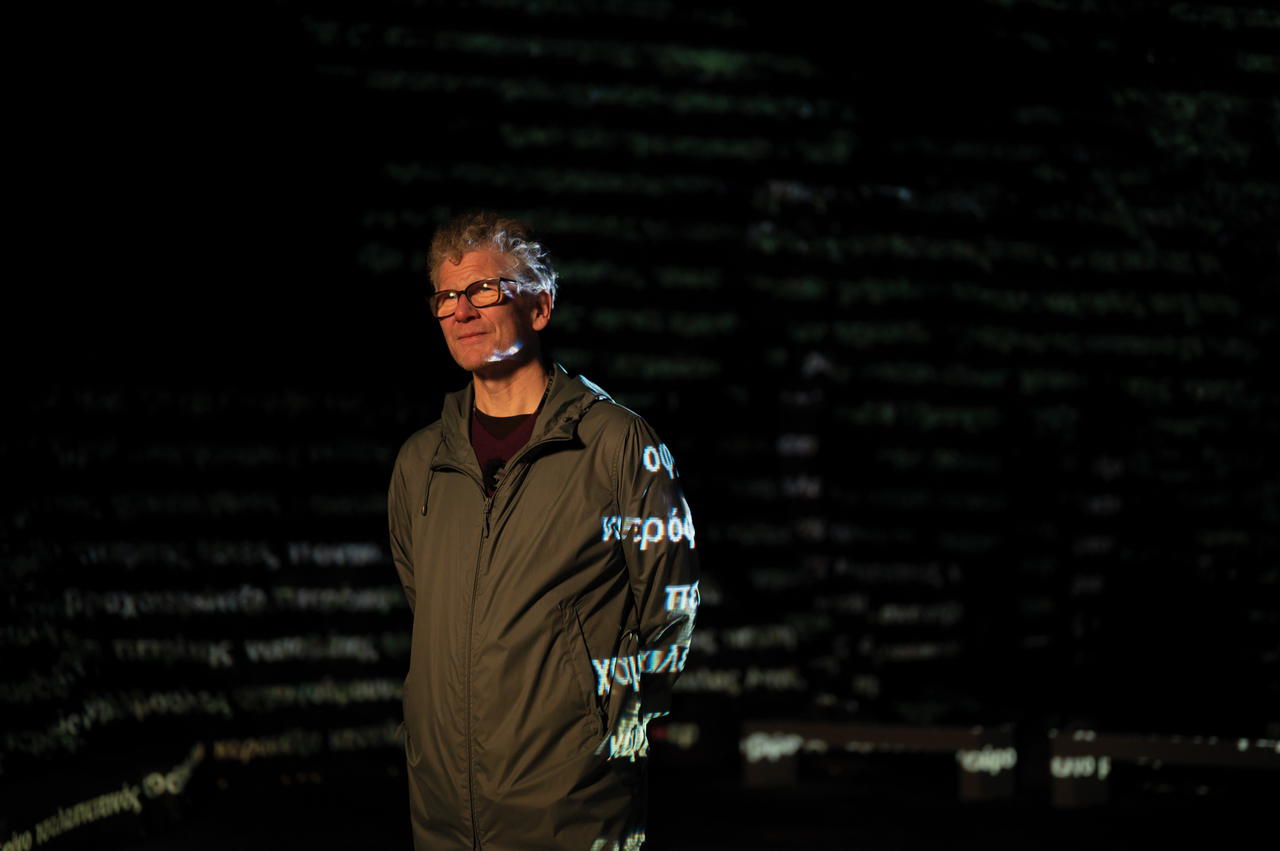

Like Dr Frankenstein in his lab, Charles Sandison works in the dark of night, conjuring life from code. His video projections—bursts of light shaped by algorithms—transform buildings, parks, and interiors across the globe, bringing his work from a studio in Finland to the world stage.

For more than three decades, Sandison has been a pioneer of site-specific, computer-generated digital art, creating mesmerising installations that weave together language, data and technology. A pioneer in using code as a creative language, he invites audiences into evolving, self-generating universes of words and signs, deeply informed by their environments and histories.

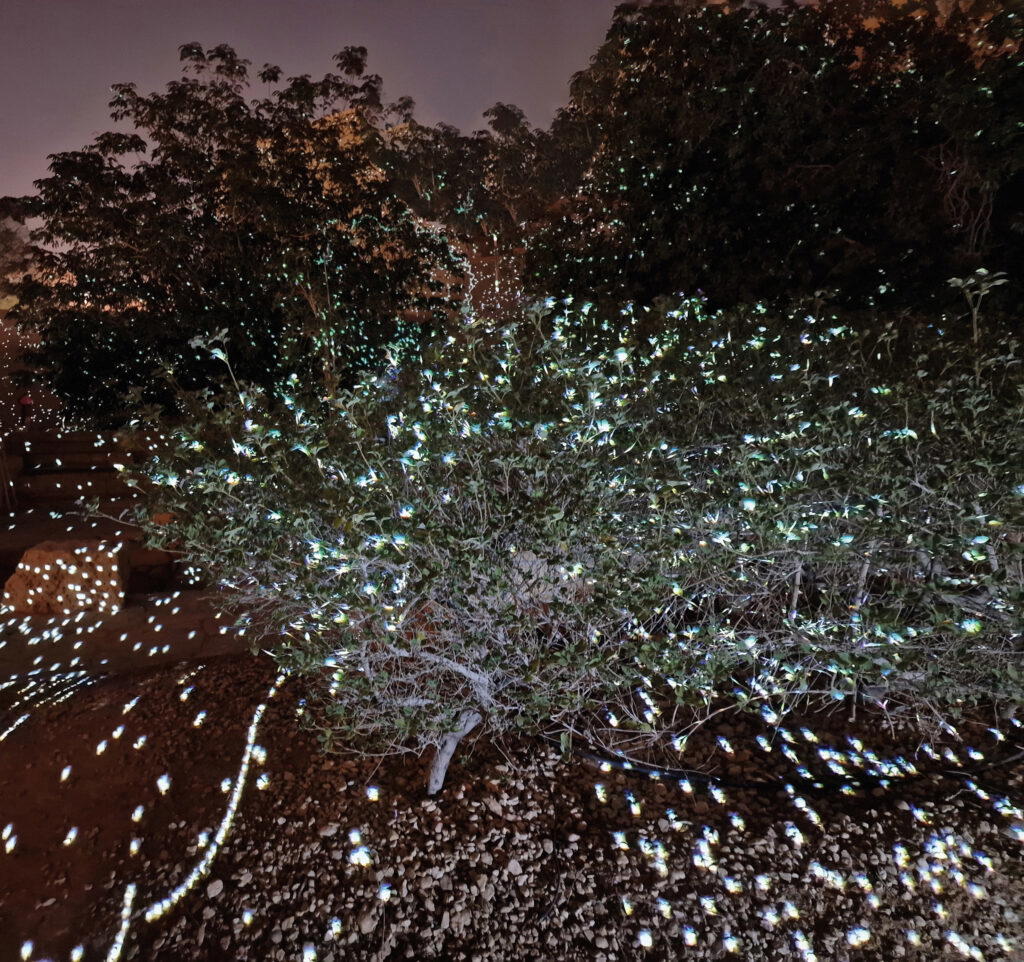

His latest and perhaps most ambitious work—‘The Garden of Pythia’ (2025)—is a permanent installation on Mount Parnassus in Delphi, Greece—a poetic fusion of artificial intelligence and ancient myth, commissioned by the Polygreen Culture & Art Initiative, which is part of Pi, the Global Centre for Circular Economy and Culture, founded by Athanasios Polychronopoulos.

The project marks Sandison’s most advanced use of AI yet—an approach he describes as deeply instinctual, with the algorithm learning his unique coding style. “It has become an extension of my brain,” he says. Rather than explain how AI works, his aim is to create an immersive experience—“a kind of communication, like when somebody looks at a painting in a museum.”

Born in Haltwhistle, Northumberland, in 1969, Sandison was raised in Wick, Scotland, a remote region of the UK that cultivated an awareness of nature and isolation. Having dyslexia—he didn’t learn to read until the age of eight—and growing up with Doctor Who and Star Trek on television, he was fascinated by machines and anything that flashed.

At 12 years old, in an era when home computers were still rare curiosities, he bought a secondhand Sinclair ZX81 model from a classmate. It quickly became his best friend, and he taught himself to code. “I was failing in mathematics and was a disaster at school,” he admits. “Meanwhile, back at home, I was coding. I had no idea why. Today, it’s something I can do in my head without a computer. I can shut my eyes and I can write code, or I can see it.”

While Sandison later trained at the Glasgow School of Art from 1987 to 1993, it was his background in coding that shaped the trajectory of his work. “Back in those days, there was no media art education,” he states.

“In the early 1990s, everybody was making it up as they went along. Then a light bulb went on in my head when I realised that painting, drawing, and writing computer code were the same thing for me.” With that, he carved out a unique niche in the international art world, with early appearances alongside the Young British Artists and wider recognition following his participation in the 2001 Venice Biennale.

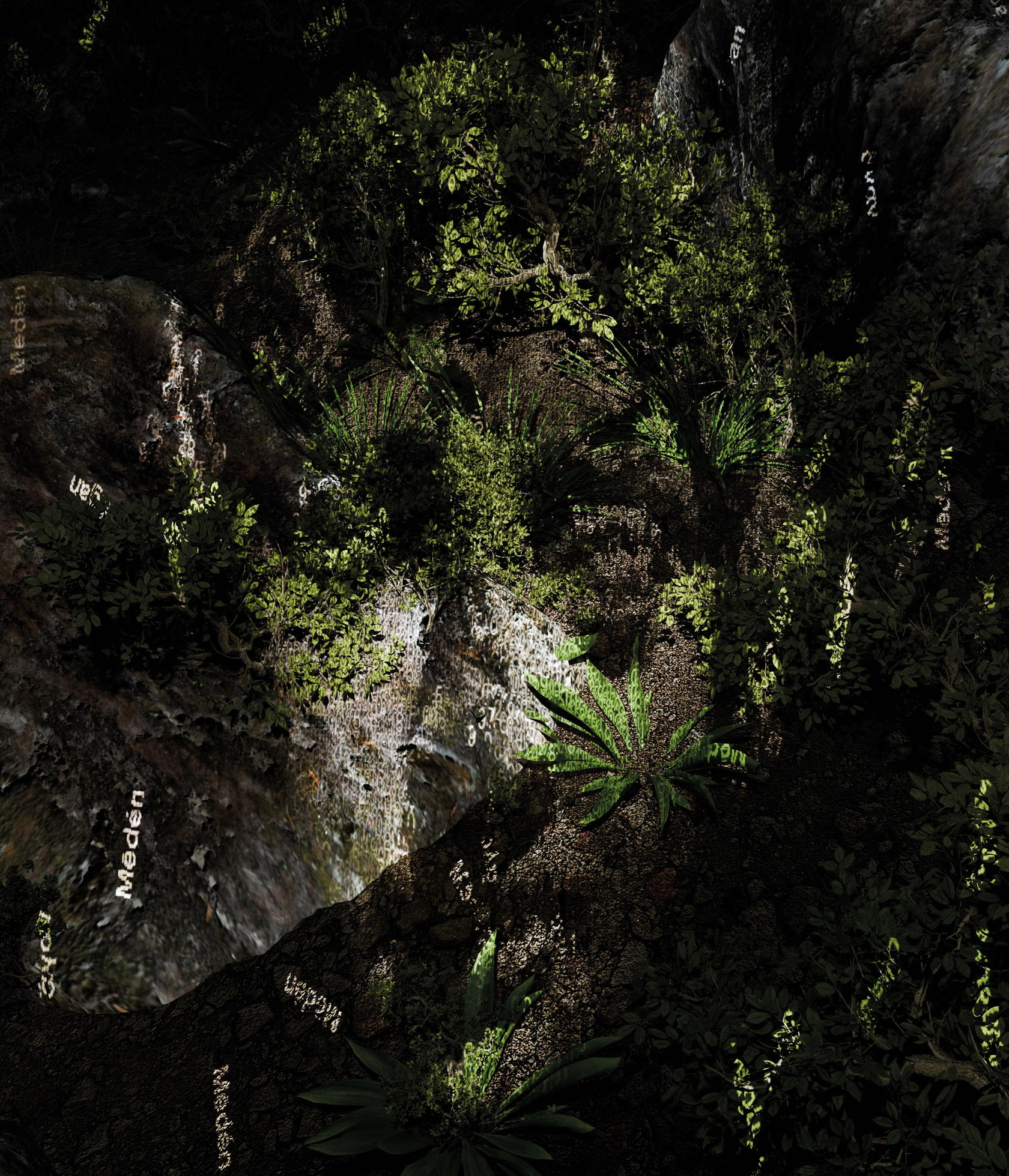

Sandison’s practice treats language and data as living systems; his artworks feel alive, constantly mutating. Using custom software written in C++, a powerful programming language known for its speed and control, he creates installations where letters, numbers and symbols crawl, glide and swarm across buildings and landscapes.

Viewers don’t just observe—they inhabit a shifting system, immersed in language in motion. These projections mirror the complexity of human thought and history, revealing patterns that are both unpredictable and profound.

Sandison sees his role not as presenting something entirely new, but as revealing what’s already there—just hidden from view. Projection, he says, acts like a flashlight or X-ray glasses, illuminating the unseen layers of the landscape. “I think the job of artists is to reveal what’s already written in this invisible bubble we live in,” he says, suggesting that consciousness isn’t about accumulating knowledge, but discerning what truly matters.

This conceptual framework finds its most potent expression in this year’s ‘The Garden of Pythia’, which spans millennia—from the prophetic Oracle of Delphi to modern AI. In it, Sandison draws a parallel between today’s algorithms and Pythia herself, whom he sees as a kind of ancient, organic computational device.

“This whole AI model is much older than we think,” he notes. “The large language model began in places like the Temple of Apollo and the Oracle of Delphi, with wealthy pilgrims coming up the hill from their boats. It was the first AI up there in a sense, a kind of biomythic intelligence, but artificial, nonetheless.”

“I think the job of artists is to reveal what’s already written in this invisible bubble we live in.”

Using environmental sensors, the installation responds in real time to changes in light and temperature. Presented on the garden at Pi, it incorporates fragments of Delphic statues, inscriptions, and texts, alongside data drawn from the local geology, flora, and fauna. Viewers are invited to consider how our questions about machines are not so different from those about oracles.

Sandison’s work demonstrates how contemporary art can span past, present, and future. It’s not just about technology, but about the enduring threads of human curiosity and symbolic language. In ‘The Garden of Pythia’, he reactivates a mythic site through machine logic, inviting audiences into the work.

“I try to create experiences to co-opt the visitor. People bring their experiences to the artwork and become a part of it. Quite often, I let the projections fall onto their bodies that become like a canvas.”

In Sandison’s view, art lives through its viewers: “As powerful as AI, artificial life, and computers are, they’re not as powerful as human consciousness. An artwork by itself is meaningless without people interacting with it and taking that experience into their lives.”