A mid-tier Chinese construction crane costs upwards of $500,000. But while many businesses reduced inventory during the height of the Covid-19 pandemic, Pollisum Engineering aggressively added cranes to its fleet. It ended up purchasing more than 30 units.

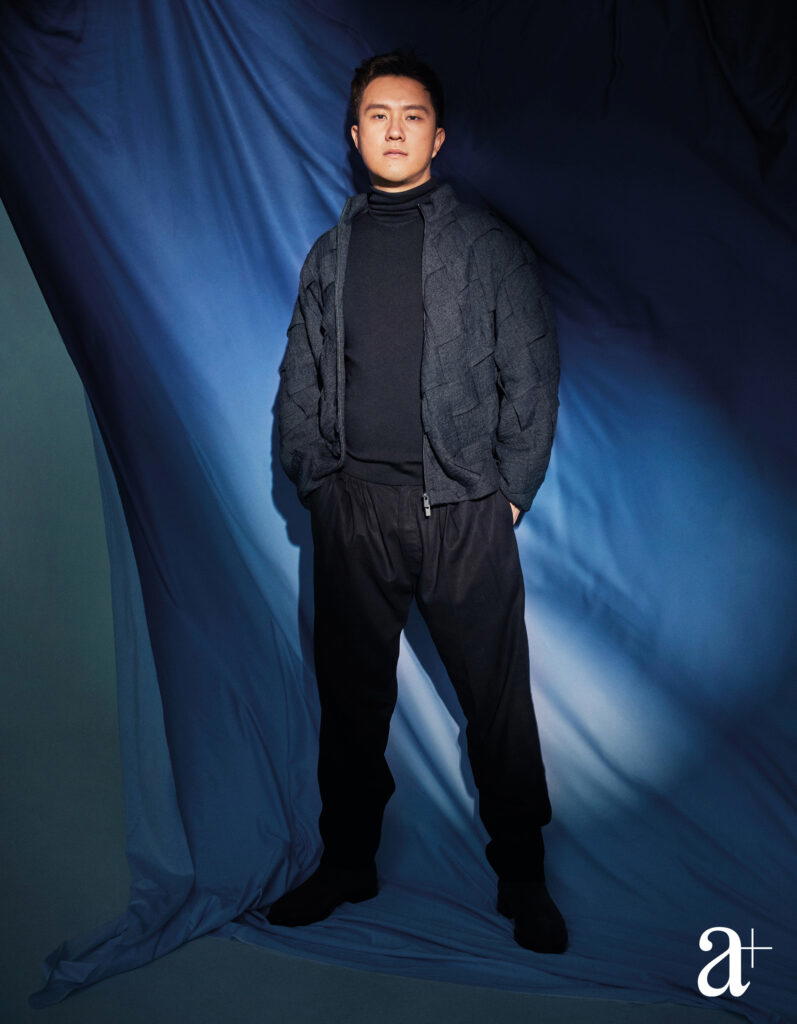

The feat was unheard of given its rung on the ladder. “Apart from the top two players in the market, no one at our level of revenue would have made such an investment back then. People were like, ‘One crane is already so expensive. How’d you dare to buy so many?’” CEO Chris Ang recounts.

It was largely propitious timing. Lockdown measures did not adversely affect many of the construction projects Pollisum was involved in; it was still necessary to construct MRT stations and train tracks, among other things. Furthermore, the government provided grants and a “super good” interest rate of two percent. Pollisum used the funds for expansion.

Founded by his father, Ang Ka San, and mother, Julia Tai, in 1984, Pollisum started as a crane mechanical repair company with a two-person outfit; his father carried out the grunt work while his mother managed cash flow. The early days were filled with pitfalls. Ang remembers his parents being hounded by creditors. The family also did not have a home at one point.

Grit turned the tide. Today, Pollisum is involved in about 80 percent of LTA’s projects. Key projects it has been a part of include the Thomson-East Coast and Jurong Region Lines, Resorts World Sentosa, Marina Bay Sands, and Changi Airport’s Terminal 5 in the near future.

The company leases cranes as well as heavy transport vehicles for transporting large, heavy, or specialised cargo. In addition, it offers maritime logistics and services, including tugboat towing and mooring assistance. It also manufactures custom construction fabrications at its headquarters at 41 Senoko Way.

Ang’s decision to double down during the pandemic ultimately led to a seismic shift in its growth trajectory. The expanded fleet opened the door to cross-hiring, allowing Pollisum to rent equipment to other companies to meet surging demand and, in turn, build a new revenue stream.The company currently has over 270 cranes and prime movers, and nearly 400 employees.

Under Ang’s stewardship, its revenue has burgeoned 250 percent to the current record high of $70 million over the last five years. With an annual compound growth rate of more than 30 percent, Pollisum is now Singapore’s fastest-growing crane leasing company.

Ang took the reins as CEO in 2025. A long-term strategy made all the difference in the company’s growing success, the 38-year-old underscores. “Many other crane companies have a ‘just buy’ mindset, but they don’t know what to do with the cranes afterwards. They buy and hope for the best and then suffer when they don’t have enough jobs. Sometimes it’s the other way around, too, as if they had a good buying opportunity but passed it up, and then missed the wave.”

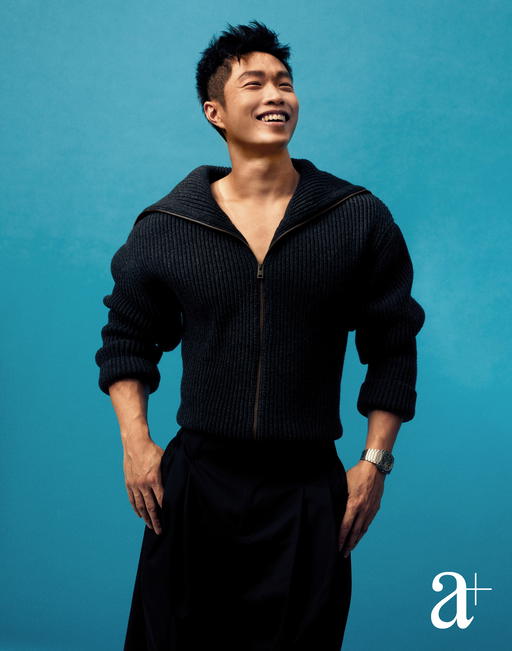

Also, the will to do whatever it takes. “Pollisum is known for being aggressive in our dealings. We’re okay with that because we have to be aggressive to be able to grow.”

NEW COMPANY CULTURE

In spite of his business acumen, Ang was once, as he puts it, a “slacker”. He was “always leeching off people” and “the sort of student to add [his] name to a group project without contributing”, he recounts with startling candour.

As a young adult, he wanted nothing more than to be an idler, marathon-gaming during the school holidays while his peers rolled up their sleeves in part-time jobs. “I just didn’t like the idea of working.”

His wake-up call came when he was bullied during national service. “I’ve always been able to talk my way out of anything, but that’s just not possible in the army—you become a target if you’re the weakest link. That experience made me decide that I’d start giving my best to everything that I do in the future,” he says.

Upon graduating with an accounting and finance degree from the University of London, he joined a bank, but left after three months because he found the culture painfully uninspiring. “Everyone was just looking forward to a tea break or knocking off at five o’clock, and I didn’t want a boring career.”

Ang worked at PwC Singapore for three years before joining the family business as a management intern in 2016. One of his first responsibilities was to revive Keow Hoe Transport, a loss-making Malaysian transport company his parents had just acquired. A timeworn fleet meant that the vehicles had low utilisation but high repair costs, so he made the call to phase it out.

He also moved the company’s transport services from Malaysia to Singapore because the profit margins are four times higher here. Keow Hoe Transport broke even less than two years after he took over.

In 2018, he was appointed business development manager and tasked with doing away with Pollisum’s underutilised fleet. It was an uphill battle, but it helped that he has “always been thick-skinned”.

“I managed to trade them in. We are one of the few crane companies in Singapore that handles so many trade-ins. How are we able to do this? It comes to a few factors, including our growth, purchase record, and the relationships we’ve built.”

Since taking the plunge during the pandemic, Pollisum has been buying some 30 cranes every year and trades in its older models. Although the Ministry of Manpower allows cranes in Singapore to be in service for 15 years, Pollisum’s cranes are on average six years old.

In 2020, Ang assumed the role of executive director and made the call to revolutionise company culture. Firstly, through transparency. Pollisum now discloses its monthly revenue to its employees.

“Most bosses don’t do it because they’re worried their employees will say, ‘Oh, the company made this amount this month, why don’t I get a salary increment?’ or ‘Why is my bonus so small?’ Our staff are our warriors, so I believe they should know this information.”

Chris Ang on being transparent

Secondly, incentives. “Like what? Money, lor,” he says without batting an eyelid. Employees now receive a token sum on a good month, and when revenue hits a new all-time high, everyone goes out to party. Then there are non-monetary initiatives that celebrate staff and the people around them. Last Valentine’s Day, for example, the company sent flower bouquets to the wives of some of its blue-collar workers. These themed gestures are carried out every month.

Also, Pollisum’s prominent annual dinner-and-dance, which made headlines in 2023 for disbursing $100,000 in prize money. One migrant employee received a cash bouquet of $18,888—an amount equivalent to one and a half years of his salary—for winning a Squid Game-themed challenge. Last year, the company gave away more than $120,000. A similar challenge resulted in another migrant employee winning $28,888 in cash.

The goal of these efforts is simple: to cultivate employee happiness and loyalty. Ang isn’t deterred by detractors. “Some people have said Pollisum is just trying to show off, but if that were the case, we wouldn’t be doing this so regularly. Any employer can give out salaries, but not every employer can touch the hearts of its employees.”

MARKET CONSOLIDATION

In Ang’s experience, taking over the reins of a family business requires, above all, a desire to outperform. “Many successors exit their family businesses after a while. They say, ‘My parents don’t trust me. They don’t give me the authority to implement new ideas’.” But our parents are the founders. They can’t be like, ‘Now that you’re here, I’ll let go,’ right? As the second generation, we need to prove ourselves. If anything, we need to show that we are hungrier than them.”

It was why he threw himself into “winning small battles consistently”, whether by hitting milestones, turning loss to profit, or securing deals. “For example, my mum has been through rough times, so she is more prudent. Sometimes she’ll be like, ‘No more buying cranes. The exposure is too big’. But that just pushes me to work out a super good deal—like us not even having to come up with any money.”

He doesn’t avoid rolling with the punches either. “I come up with all sorts of proposals to convince her on certain things. So, when I hear ‘My parents don’t trust me’, I think, ‘Did you really think of new ways to convince them?’ If you show that you’ve minimised risk and done forward planning, most bosses will be accepting.”

Manpower is his biggest challenge in running Pollisum. In Singapore, one can only be an approved crane erector after five years of relevant practical experience, so there is at times a lack of operators. However, Ang believes that crane operations will, as with many things, eventually become automated.

It is why the arduous task of digitalising all company processes is afoot. “It’s not just about doing away with paper but also training our operators to be more mobile-savvy. It will, for example, prevent scenarios where they look at handwritten notes and say, ‘Eh, what’d you write?’ This happens a lot.”

It’s no surprise that Ang’s five-year roadmap centres on a multi-pronged strategy, with mergers and acquisitions playing a key role and an IPO a potential pathway as the business continues to scale up. The transport and heavy-lifting company Gim Sen Transportation Services has been part of the Pollisum Group since September, and negotiations are underway to acquire more companies.

To lay the cornerstone for market consolidation, Ang also recently hired Pollisum’s first-ever CFO to help raise capital, assess investors, and get the best price and terms for the equity. At present, his father is executive chairman, and his mother, managing director.

Another strategic step is expansion into foreign markets, with Pollisum setting its sights on Australia. As the country ramps up investment in renewable-energy infrastructure, it is building the physical systems and organisational networks required to reach net-zero—a transition that will inevitably drive demand for cranes.

As someone who earned his stripes, Ang doesn’t believe that legacy planning means his four-year-old daughter will take over the business in the future. “A legacy must be earned, it is not given. I will pass my role on to the person who is the best fit for the job,” he avers.

“Having said that, I believe that unless a business has become an MNC, it’s very hard to find a CEO who is as driven as either the founder or someone who took it to new heights. I think this challenge has contributed to many downfalls.”

But that won’t be happening anytime soon. For now, he says, the priority is strengthening the company’s spine for the next phase. “I’ve told my staff that we’re currently in a dangerous position. I’ve been studying the market and have observed that, over the past 10 years, the companies in our industry ranked between three and seven have been hovering at $40 million to $60 million in revenue for the longest time. To him, it is a reminder that Pollisum could also settle into that same long-term plateau if nothing changes.

“I tell my staff to expect change. There will definitely be change.”

Photography Mun Kong

Styling Chia Wei Choong

Grooming Tiffany Fang