The one thing fossil hunting requires more than luck is money. Unless an agreement has been drawn up with the landowner, the land to be excavated has to be purchased. Then, a crew is hired and equipment rented to carry out the digging. The fossils are later sent for restoration.

Imaginably, the enormous expenditure is something few museums and universities can afford, so the endeavour sometimes becomes a fool’s errand. “Some institutions in Europe have had to let go of fossil sites because they lacked funding. Those sites later became landfills. Can you imagine that?” says Cliff Hartono.

The Germany-born, Singapore-raised fossil and crystal dealer has been in the business for over a decade. In his previous life, he held a finance job in London, but toyed with the idea of fossil dealing when he found himself spending his weekends at the Natural History Museum. Soon after starting his own collection of fossils, he decided to make a career switch.

Given that the purchase and sale of fossils are typically legal in the US and Europe, so Hartono spent a few months travelling around those areas after walking away from his trading screens. Whether it was luck or affinity, the greenhorn had little difficulty in getting veteran fossil hunters and dealers to show him the ropes.

“I’d approached one of them out of the blue at an exhibition saying, ‘Hey, I just quit my job and really want to be a fossil dealer. Do you have any advice?’ he recounts. “He looked at me sceptically and said, ‘Well, I’m going on a dig in Salt Lake City in two weeks. If you fly over, I’ll pick you up’. I’d only met him once, so when I was at the airport, I thought, ‘Well, this is going to be interesting’. But he actually showed up.”

By early 2013, Hartono had accumulated enough fossil pieces to launch Set in Stone Gallery. For his first show, which was held in Singapore, he had for sale fossils of fish, ammonites, and other types of shells. The highlight was the fossil of an ichthyosaur, a marine reptile similar in appearance to a dolphin.

Even though it was the priciest piece of the lot, it was snapped up within a week. The sale earned him credibility. “People in the industry were like, ‘Wow, this guy just started, and he has already managed to sell an ichthyosaur’.”

His modus operandi evolved along with the business. In the beginning, he added fossils to his catalogue by choosing what he liked or found beautiful. “I’d think, ‘Okay, if nothing sells, at least I’ll have a fossil collection I’d be happy to keep’,” he lets on with a guffaw. Now that he has established a clientele, most of whom are private collectors, he selects pieces according to what they tell him they like or are looking for. Essentially, he now largely shops for clients, so he no longer has to hope to be able to sell his inventory.

There are several controversies in the realm of fossil dealing. For one, although the practice is banned in countries like Argentina, Brazil, China, and Mongolia, noncompliance has resulted in scores of fossils of dubious origins. Not that black market dealers necessarily want to contravene laws or have bad intentions—many just think the fossils can be put to better use. “They feel that these fossils aren’t properly appreciated when they’re left in the desert to weather out,” Hartono explains.

Nonetheless, no self-respecting fossil dealer would touch illegal fossils with a 10-foot pole. The trouble just isn’t worth it. He cites an instance, where a dinosaur fossil from Mongolia was put up for auction in the US. “The Mongolian government protested, and a lawyer with an injunction burst into the room in the middle of the auction to put a stop to it. It must have been quite dramatic,” he says. “It was a big case and made other dealers go, ‘Okay, let’s not try our luck anymore’.”

Then there was the issue of whether or not the private sales of fossils should be allowed. Private sales, it has been argued, hinder scientists from conducting valuable research because they drive up prices—and institutions have modest budgets.

However, given the exorbitant nature of excavation projects, Hartono says, it is thanks to private sales that many of them can be carried out. The current coexistence between museums and the private market, he notes, is evidence of the growing recognition of the advantages of private collections.

It helps that most fossil hunters and dealers are in this field out of passion, so they take into account greater good in transactions.

“I can’t think of any respectable fossil dealer who wouldn’t give a massive discount to a museum as opposed to a private collector. A lot of us hope that the fossils end up in museums, and if in private collections, that they are displayed somewhere people can admire them.”

Cliff Hartono on the hope to benefit a wider audience

This is why, unlike before, many fossil hunters now carefully document individual fossil pieces during excavation. They want to help preserve as much scientific information as possible.

Passion, he adds, is why many fossil hunters still throw themselves into the gruelling work even when they no longer need to. “Many can retire at any time. They’ve sold millions of dollars worth of fossils. Yet, they still go out there and hunt for fossils that sell for $100 or $200 because they’re that enthusiastic.”

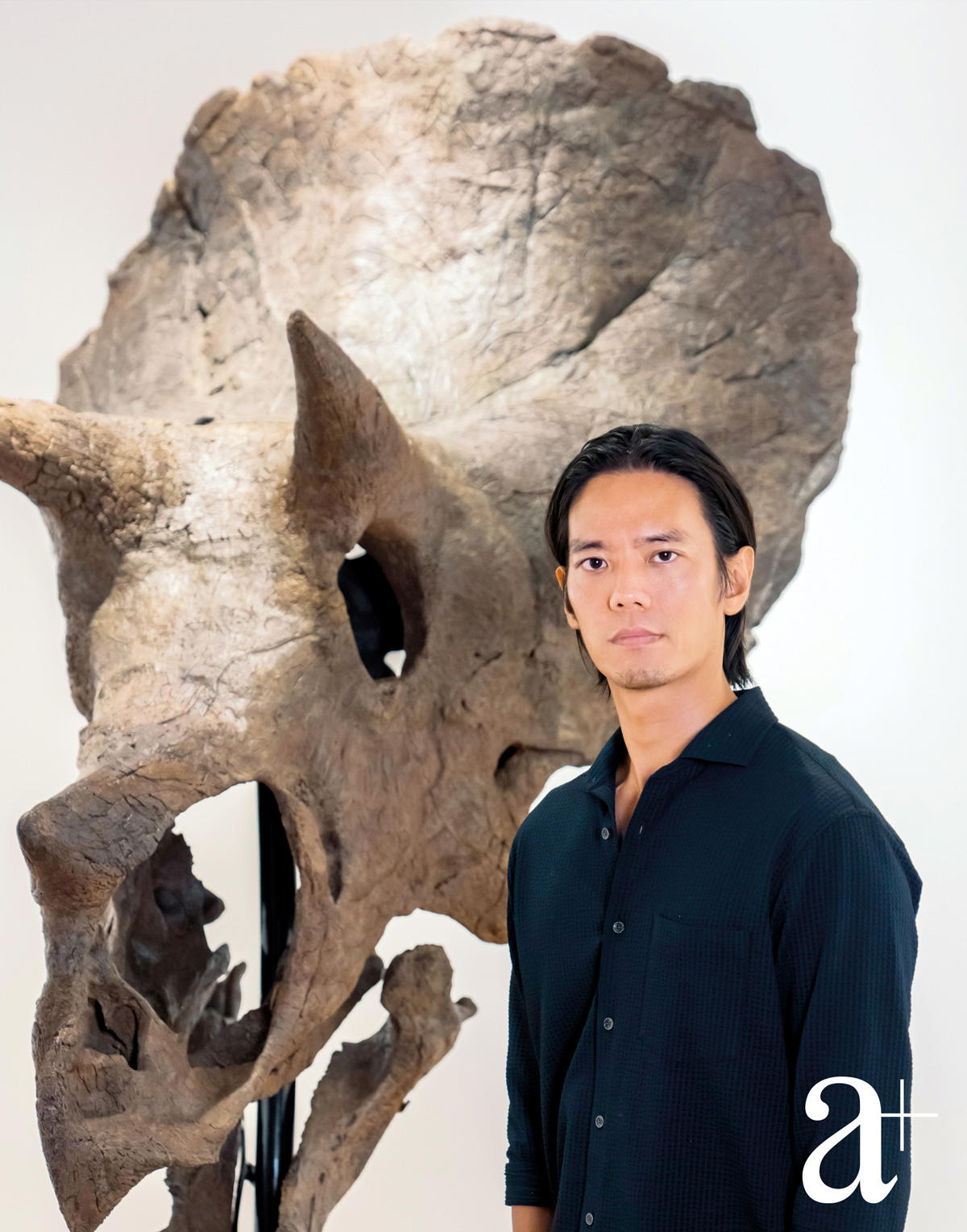

Hartono’s latest fossil in his collection is his rarest yet: a Triceratops skull comprising 62 percent of the original bone specimen. It was found on private land in Montana with its horns intact. Because fossils are always found in fragments, they require copious amounts of restoration work, so the figure is nothing out of the ordinary.

Interestingly, authentication isn’t necessary. A site that has been marked for excavation is always carbon dated beforehand, so anything it contains is understood to have been from that period and locality.

Burgeoning interest in dinosaur skulls among his clients means this addition comes at an opportune time. Hartono reckons that the affluent in Singapore are realising that dinosaur fossils make great alternative investments. Before the pandemic, a Triceratops skull used to sell for between US$100,000 (S$134,000) and US$250,000, but in recent years, it has been selling for US$500,000 to US$700,000. Skulls that have sold in Europe have even crossed the million-dollar mark.

The sale of Stan, a Tyrannosaurus rex skeleton, during the pandemic, might have had something to do with the surge. Up until last month, it was the most expensive dinosaur specimen and fossil ever sold at auction for US$31.8 million.

For this reason, Hartono is confident that the skull in his possession will end up in somebody’s shopping cart. What he can’t say for sure, however, is if it will be able to call Singapore home. While he hopes to make the sale in Singapore to help grow the market here, the general scarcity of space here, he says, will make it tricky to find someone willing to buy it for a home or the lobby of a commercial space.

Because shows involve an arduous number of moving parts, Hartono holds them a lot less these days. “People think shipping fossils is like ordering something from Amazon. ‘Click’ and they’re right there. But when you find a fossil, you have to arrange for transportation to move it from the dig site to the city, and then arrange for transportation to the lab,” he illustrates.

“To put a collection together, I need to make sure I still have the pieces clients have already purchased in my inventory, and coordinate shipments from various parts of the world to ensure they all arrive together. It’s difficult.”

He sees himself fossil dealing for a long time. “If you’d asked me back then if I’d still be doing this 12 years later, I wouldn’t have been able to imagine it. But if you ask me now whether I’ll still be doing this for another 10 or 20 years, my answer would be, ‘I hope so’,” he says.

“Seeing the faces of clients, who have been waiting for something for months makes me happy. Then, there are people in the industry who have become like family. I hope to be able to do this for the rest of my life.”