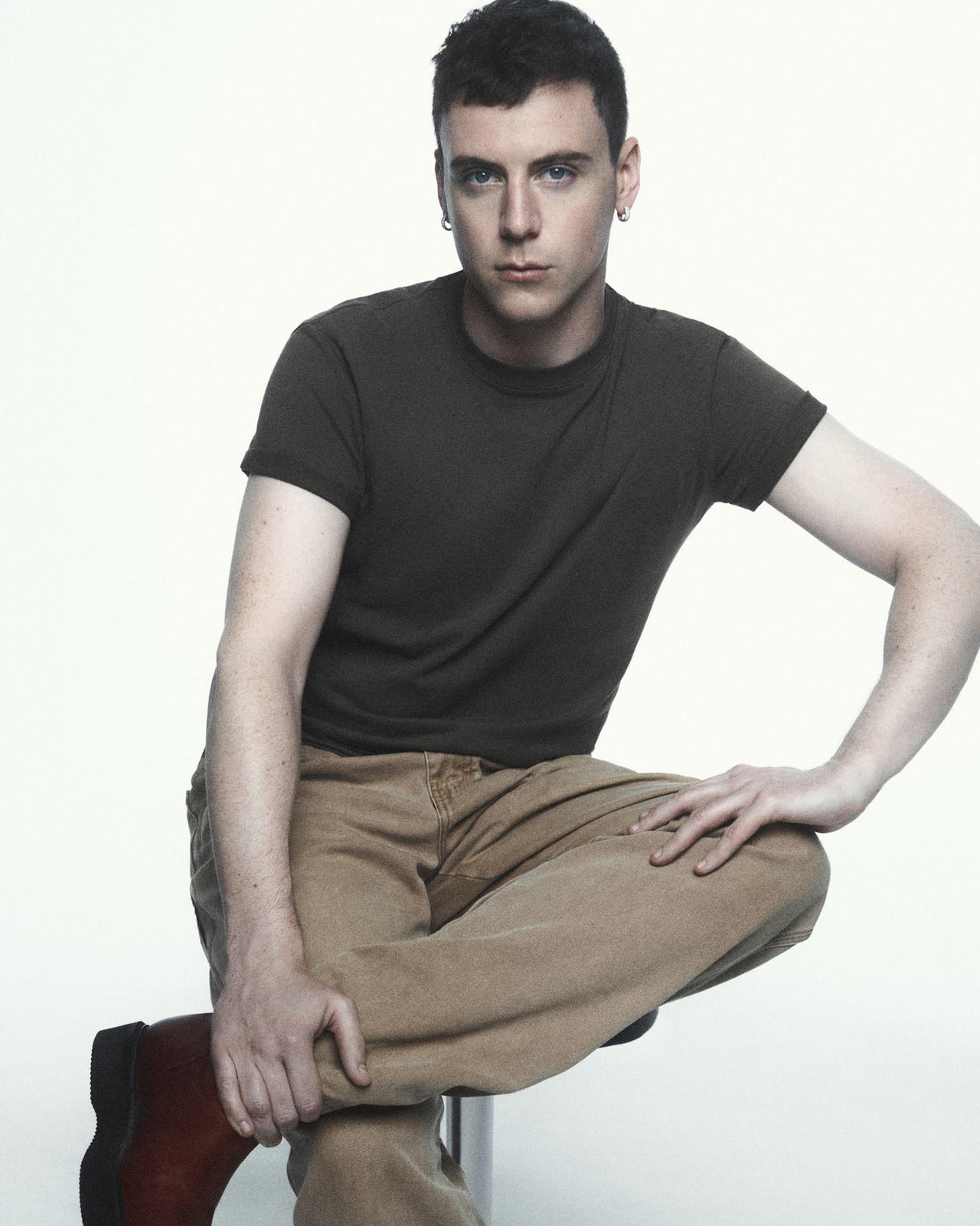

Imagine helming the creative direction of a celebrated brand like Alexander McQueen for 13 years (after working under its late founder for 13 years), only to be replaced by a white male hired from another brand—such was Sarah Burton’s fate. That’s not to say that newly appointed creative director Seán McGirr is not talented—I’m sure he is, having worked at several brands, including JW Anderson where he was previously head of ready-to-wear. In any case, it is disheartening to see yet another white male given the keys to a major fashion house.

With McGirr’s hiring, all six luxury fashion houses owned by Kering are now led by white men. The fact that Kering prides itself on promoting gender equality in the workplace makes this particularly disappointing. The group’s manifesto on “empowering women” talks about Kering’s commitment “to gender equality and to the development of talented women in all its entities and at all levels of the organisation”. While that has resulted in a significant number of women in the group’s workforce—Kering cites that 63 per cent of its total headcount are women—none are in its most visible position as creative directors.

One can argue that hiring for the sake of ticking off diversity checkboxes shouldn’t be encouraged. I strongly agree. Talent should always be at the forefront of hiring a creative director, but the fact that it disproportionately goes to men more than women is baffling.

While we may not be privy to the hiring processes of fashion houses, the fact remains that the majority of fashion students are female. Statistics across the board show that female students far outnumber male students in fashion majors, but beyond these institutions, men are largely in charge. Could it be that not a single female student out of 82 percent (a statistic of Fashion Institute of Technology students in 2022) made the cut? That seems unlikely.

Post-graduation, the numbers remain consistent. A 2021 report by Data USA showed that 84.2 percent of fashion designers in the US were women, but it didn’t reflect the female designers helming brands. A 2016 analysis by Business of Fashion reported that out of the 371 designers heading 313 brands surveyed during the 2017 spring/summer women’s fashion week across New York, London, Milan, and Paris, only 40.2 percent were women.

You would think that even with the trend of houses looking to promote unknown designers instead of cycling through an existing roster of creative directors, women would get a higher chance. Clearly, that’s not the case.

Before McGirr’s appointment, there was Bottega Veneta’s Matthieu Blazy, Alaïa’s Pieter Mulier, Gucci’s Sabato de Sarno, Bally’s Simone Bellotti, and Stefano Gallici for Ann Demeulemeester. All were hired as creative directors through internal promotions or poached from behind-the-scenes positions at other brands.

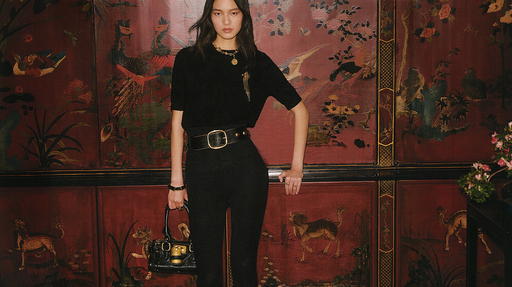

Phoebe Philo is often cited as an example of a female creative director. Her work at Céline (the old, accented one) exemplified the need for more women in influential creative roles. As a woman, she understood how women wanted to dress, especially those who didn’t want to feel like they had to show skin to look and feel sexy.

It’s not that a man wouldn’t be able to achieve the same reverence—Azzedine Alaïa is one of many examples—but a female perspective on designs meant to be worn by women feels undoubtedly more empowering.

A company’s diversity adds more value than it subtracts. It’s been proven time and time again that deviating from the traditional role of a white male creative director offers untold possibilities. For example, the late Virgil Abloh’s ascension to creative director of Louis Vuitton’s menswear division crafted a more culturally aware fashion house, widening its community and embracing lived experiences from the perspective of a Black man.

The same applies to having a female creative director. Clare Waight Keller’s time at Givenchy often stayed true to the fashion house while incorporating contemporary nuances. Replacing her with Matthew Williams—a buzzy designer with a streetwear-leaning brand—stripped it all away in favour of collections that, while modern, felt far removed from Givenchy’s refined softness.

Diversity is nuanced. There may be a host of factors why white men often take on the creative reins of a fashion house but it’s also hard to not dismiss these factors as systemic. If Kering wants to be as competitive as its conglomerate counterpart LVMH, perhaps taking a leaf from its book might be beneficial.

Why be bland when you can be different and empower women more publicly?